So far, we have assumed that different perceivers will all form pretty much the same impression of the same person. For instance, if two people are both thinking about their mutual friend Janetta, or describing her to someone else, they should each think about or describe her in pretty much the same way. After all, Janetta is Janetta, and she should have a personality that they can both see. But this is not always the case; they may form different impressions of Janetta for a variety of reasons. For one, the two people’s experiences with Janetta may be somewhat different. If one sees her in different places and talks to her about different things than the other, then they will each have a different sample of behavior on which to base their impressions.

But they might even form different impressions of Janetta if they see her performing exactly the same behavior. To every experience, each of us brings our own schemas, attitudes, and expectations. In fact, the process of interpretation guarantees that we will not all form exactly the same impression of the people that we see. This, of course, reflects a basic principle that we have discussed throughout this book—our prior experiences color our current perceptions.

One factor that influences how we perceive others is the current cognitive accessibility of a given person characteristic—that is, the extent to which a person characteristic quickly and easily comes to mind for the perceiver. Differences in accessibility will lead different people to attend to different aspects of the other person. Some people first notice how attractive someone is because they care a lot about physical appearance—for them, appearance is a highly accessible characteristic. Others pay more attention to a person’s race or religion, and still others attend to a person’s height or weight. If you are interested in style and fashion, you would probably first notice a person’s clothes, whereas another person might be more likely to notice a person’s athletic skills.

You can see that these differences in accessibility will influence the kinds of impressions that we form about others because they influence what we focus on and how we think about them. In fact, when people are asked to describe others, there is often more overlap in the descriptions provided by the same perceiver about different people than there is in those provided by different perceivers about the same target person (Dornbusch, Hastorf, Richardson, Muzzy, & Vreeland, 1965; Park, 1986). If someone cares a lot about fashion, that person will describe friends on that dimension, whereas if someone else cares about athletic skills, he or she will tend to describe friends on the basis of those qualities. These differences reflect the emphasis that we as observers place on the characteristics of others rather than the real differences between those people. Our view of others may sometimes be more informative about us than it is about them.

People also differ in terms of how carefully they process information about others. Some people have a strong need to think about and understand others. I’m sure you know people like this—they want to know why something went wrong or right, or just to know more about anyone with whom they interact. Need for cognition refers to the tendency to think carefully and fully about our experiences, including the social situations we encounter (Cacioppo & Petty, 1982). People with a strong need for cognition tend to process information more thoughtfully and therefore may make more causal attributions overall. In contrast, people without a strong need for cognition tend to be more impulsive and impatient and may make attributions more quickly and spontaneously (Sargent, 2004). In terms of attributional differences, there is some evidence that people higher in need for cognition may take more situational factors into account when considering the behaviors of others. Consequently, they tend to make more tolerant rather than punitive attributions about people in stigmatized groups (Van Hiel, Pandelaere, & Duriez, 2004).

Although the need for cognition refers to a tendency to think carefully and fully about any topic, there are also individual differences in the tendency to be interested in people more specifically. For instance, Fletcher, Danilovics, Fernandez, Peterson, and Reeder (1986) found that psychology majors were more curious about people than were natural science majors. In turn, the types of attributions they tend to make about behavior may be different.

Individual differences exist not only in the depth of our attributions but also in the types of attributions we tend to make about both ourselves and others (Plaks, Levy, & Dweck, 2009). Some people are entity theorists who tend to believe that people’s traits are fundamentally stable and incapable of change. Entity theorists tend to focus on the traits of other people and tend to make a lot of personal attributions. On the other hand, incremental theorists are those who believe that personalities change a lot over time and who therefore are more likely to make situational attributions for events. Incremental theorists are more focused on the dynamic psychological processes that arise from individuals’ changing mental states in different situations.

In one relevant study, Molden, Plaks, and Dweck (2006) found that when forced to make judgments quickly, people who had been classified as entity theorists were nevertheless still able to make personal attributions about others but were not able to easily encode the situational causes of a behavior. On the other hand, when forced to make judgments quickly, the people who were classified as incremental theorists were better able to make use of the situational aspects of the scene than the personalities of the actors.

Individual differences in attributional styles can also influence our own behavior. Entity theorists are more likely to have difficulty when they move on to new tasks because they don’t think that they will be able to adapt to the new challenges. Incremental theorists, on the other hand, are more optimistic and do better in such challenging environments because they believe that their personality can adapt to the new situation. You can see that these differences in how people make attributions can help us understand both how we think about ourselves and others and how we respond to our own social contexts (Malle, Knobe, O’Laughlin, Pearce, & Nelson, 2000).

Research Focus: How Our Attributions Can Influence Our School Performance

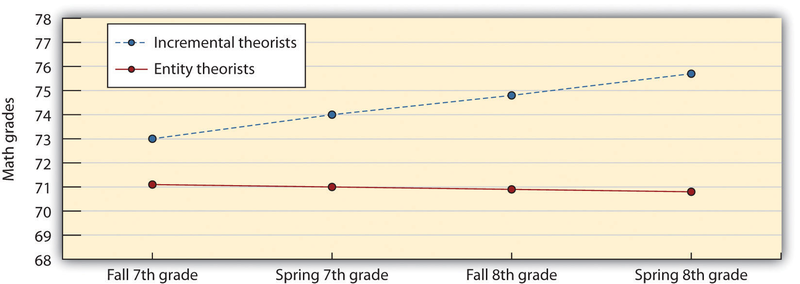

Carol Dweck and her colleagues (Blackwell, Trzesniewski, & Dweck, 2007) tested whether the type of attributions students make about their own characteristics might influence their school performance. They assessed the attributional tendencies and the math performance of 373 junior high school students at a public school in New York City. When they first entered seventh grade, the students all completed a measure of attributional styles. Those who tended to agree with statements such as “You have a certain amount of intelligence, and you really can’t do much to change it” were classified as entity theorists, whereas those who agreed more with statements such as “You can always greatly change how intelligent you are” were classified as incremental theorists. Then the researchers measured the students’ math grades at the end of the fall and spring terms in seventh and eighth grades. As you can see in the following figure, the researchers found that the students who were classified as incremental theorists improved their math scores significantly more than did the entity students. It seems that the incremental theorists really believed that they could improve their skills and were then actually able to do it. These findings confirm that how we think about traits can have a substantial impact on our own behavior.

Carol Dweck and her colleagues (Blackwell, Trzesniewski, & Dweck, 2007) tested whether the type of attributions students make about their own characteristics might influence their school performance. They assessed the attributional tendencies and the math performance of 373 junior high school students at a public school in New York City. When they first entered seventh grade, the students all completed a measure of attributional styles. Those who tended to agree with statements such as “You have a certain amount of intelligence, and you really can’t do much to change it” were classified as entity theorists, whereas those who agreed more with statements such as “You can always greatly change how intelligent you are” were classified as incremental theorists. Then the researchers measured the students’ math grades at the end of the fall and spring terms in seventh and eighth grades. As you can see in the following figure, the researchers found that the students who were classified as incremental theorists improved their math scores significantly more than did the entity students. It seems that the incremental theorists really believed that they could improve their skills and were then actually able to do it. These findings confirm that how we think about traits can have a substantial impact on our own behavior.

- 12121 reads