Although we have talked about it indirectly, we have not yet tried to define love itself—and yet it is obviously the case that love is an important part of many close relationships. Social psychologists have studied the function and characteristics of romantic love, finding that it has cognitive, affective, and behavioral components and that it occurs cross-culturally, although how it is experienced may vary.

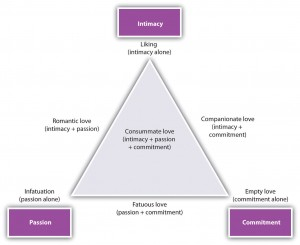

Robert Sternberg and others (Arriaga & Agnew, 2001; Sternberg, 1986) have proposed a triangular model of love, an approach that suggests that there are different types of love and that each is made up of different combinations of cognitive and affective variables, specified in terms of passion, intimacy, and commitment. The model, shown in Figure 7.9, suggests that only consummate love has all three of the components (and is probably experienced only in the very best romantic relationships), whereas the other types of love are made up of only one or two of the three components. For instance, people who are good friends may have liking (intimacy) only or may have known each other so long that they also share commitment to each other (companionate love). Similarly, partners who are initially dating might simply be infatuated with each other (passion only) or may be experiencing romantic love (both passion and liking but not commitment).

The triangular model of love, proposed by Robert Sternberg. Note that there are seven types of love, which are defined by the combinations of the underlying factors of intimacy, passion, and commitment. From Sternberg (1986).

Research into Sternberg’s theory has revealed that the relative strength of the different components of love does tend to shift over time. Lemieux and Hale (2002) gathered data on the three components of the theory from couples who were either casually dating, engaged, or married. They found that while passion and intimacy were negatively related to relationship length, that commitment was positively correlated with duration. Reported intimacy and passion scores were highest for the engaged couples.

As well as these differences in what love tends to look like in close relationships over time, there are some interesting gender and cultural differences here. Contrary to some stereotypes, men, on average, tend to endorse beliefs indicating that true love lasts forever, and to report falling in love more quickly than women (Sprecher & Metts, 1989). In regards to cultural differences, on average, people from collectivistic backgrounds tend to put less emphasis on romantic love than people from more individualistic countries. Consequently, they may place more emphasis on the companionate aspects of love, and relatively less on those based on passion (Dion & Dion, 1993).

Research Focus: Romantic Love Reduces Our Attention to Attractive Others

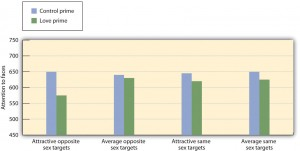

Evolutionary psychologists have proposed that we experience romantic love to help increase our evolutionary fitness (Taylor & Gonzaga, 2006). According to this idea, love helps couples work together to improve the relationship by coordinating and planning activities and by increasing commitment to the partnership. If love acts as a “commitment device,” it may do so in part by helping people avoid being attracted to other people who may pose a threat to the stability of the relationship (Gonzaga, Haselton, Smurda, Davies, & Poore, 2008; Sabini & Silver, 2005). Jon Maner and his colleagues (Maner, Rouby, & Gonzaga, 2008) tested this idea by selecting a sample of participants who were currently in a committed relationship and manipulating the extent to which the participants were currently experiencing romantic love for their partners. They predicted that the romantic love manipulation would decrease attention to faces of attractive opposite-sex people. One half of the participants (the romantic love condition) were assigned to write a brief essay about a time in which they experienced strong feelings of love for their current partner. Participants assigned to the control condition wrote a brief essay about a time in which they felt extremely happy. After completing the essay, participants completed a procedure in which they were shown a series of attractive and unattractive male and female faces. The procedure assessed how quickly the participants could shift their attention away from the photo they were looking at to a different photo. The dependent variable was the reaction time (in milliseconds) with which participants could shift their attention. Figure 7.10 shows the key findings from this study.

Activating thoughts and feelings of romantic love reduced attention to faces of attractive alternatives. Attention to other social targets remained unaffected. Data are from Maner et al. (2008). As you can see in Figure 7.10, the participants who had been asked to think about their thoughts and feelings of love for their partner were faster at moving their attention from the attractive opposite-sex photos than were participants in any of the other conditions. When experiencing feelings of romantic love, participants’ attention seemed repelled, rather than captured, by highly attractive members of the opposite sex. These findings suggest that romantic love may inhibit the perceptual processing of physical attractiveness cues—the very same cues that often pose a high degree of threat to the relationship.

- 4571 reads