The United States continues to be an extremely violent country, much more so than other countries that are similar to it in many ways, such as Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and the Western European countries. On the other hand, other countries in Eastern Europe, Africa, Asia, and South America have more violence than does the United States. These differences show that cultures vary dramatically in how, and how much, their members aggress against each other.

When children enter a violent culture such as that of the United States, they may be socialized to be even more violent. In a study of students at a high school near Detroit, Michigan, Souweidane and Huesmann (1999) found that the children who had been born in the United States were more accepting of aggression than were children who had emigrated from the Middle East, especially if they did so after the age of 11. And in a sample of Hispanic schoolchildren in Chicago, children who had been in the United States longer showed greater approval of aggression (Guerra, Huesmann, & Zelli, 1993).

In addition to differences across cultures, there are also regional differences in the incidences of violence—for example, in different parts of the United States. The Research Focus below describes one of these differences—variations in a social norm that condones and even encourages responding to insults with aggression, known as the culture of honor.

Research Focus: The Culture of Honor

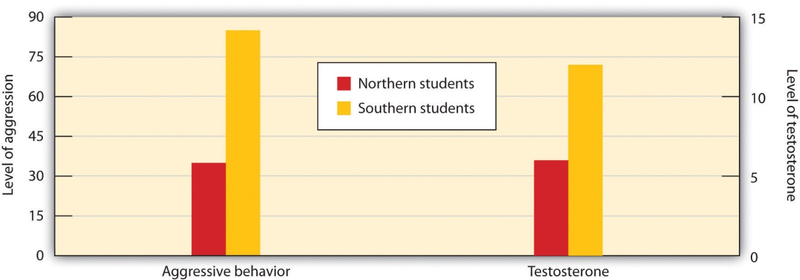

In the United States, the homicide rate is significantly higher in the southern and western states but lower in the eastern and northern states. One explanation for these differences is in terms of variation in cultural norms about the appropriate reactions to threats against one’s social status. These cultural differences apply primarily to men; some men react more violently than others when they believe that others are threatening them. The social norm that condones and even encourages responding to insults with aggression (the culture of honor) leads even relatively minor conflicts or disputes to be seen as challenges to one’s social status and reputation and can therefore trigger aggressive responses. The culture of honor is more prevalent in areas that are closer to the equator, including the southern parts of the United States. In one series of experiments (Cohen, Nisbett, Bosdle, & Schwarz, 1996), researchers investigated how White male students who had grown up either in the northern or in the southern regions of the United States responded to insults (Figure 9.12). The experiments, which were conducted at the University of Michigan (located in the northern United States), involved an encounter in which the research participant was walking down a narrow hallway. The experimenters enlisted the help of a confederate who did not give way to the participant but who rather bumped into the participant and insulted him. Compared with northerners, students from the south who had been bumped were more likely to think that their masculine reputations had been threatened, exhibited greater physiological signs of being upset, had higher testosterone levels, engaged in more aggressive and dominant behavior (gave firmer handshakes), and were less willing to yield to a subsequent confederate.

In another test of the impact of culture of honor, Cohen and Nisbett (1997) sent letters to employers all over the United States from a fictitious job applicant who admitted having been

convicted of a felony. To half the employers, the applicant reported that he had impulsively killed a man who had been having an affair with his fiancée and then taunted him about it in a

crowded bar. To the other half, the applicant reported that he had stolen a car because he needed the money to pay off debts. Employers from the south and the west, places in which the

culture of honor is strong, were more likely than employers in the north and east to respond in an understanding and cooperative way to the letter from the convicted killer, but there were no

cultural differences for the letter from the auto thief. A culture of honor, in which defending the honor of one’s reputation, family, and property is emphasized, may be a risk factor for

school violence. More students from culture-of-honor states (i.e., southern and western states) reported having brought a weapon to school in the past month than did students from

non-culture-of-honor states (i.e., northern and eastern states). Furthermore, over a 20-year period, culture-of-honor states had more than twice as many school shootings per capita as

non-culture-of-honor states, suggesting that acts of school violence may be a response of defending one’s honor in the face of perceived social humiliation (Brown, Osterman, & Barnes,

2009).

One possible explanation for regional differences in the culture of honor involves the kind of activities typically engaged in by men in the different regions (Nisbett & Cohen, 1996).

While people in the northern parts of the United States were usually farmers who grew crops, people from southern climates were more likely to raise livestock. Unlike the crops grown by the

northerners, the herds were mobile and vulnerable to theft, and it was difficult for law enforcement officials to protect them. To be successful in an environment where theft was common, a

man had to build a reputation for strength and toughness, and this was accomplished by a willingness to use swift, and sometimes violent, punishment against thieves. Areas in which livestock

raising is more common also tend to have higher status disparities between the wealthiest and the poorest inhabitants (Henry, 2009). People with low social status are particularly likely to

feel threatened when they are insulted and are particularly likely to retaliate with aggression.

In summary, as in virtually every case, a full understanding of the determinants of aggression requires taking a person-situation approach. Although biology, social learning, the social situation, and culture are all extremely important, we must keep in mind that none of these factors alone predicts aggression but that they work together to do so. For instance, we have seen that testosterone predicts aggressive behavior. But this relationship is stronger for people with low socioeconomic status than for those with higher socioeconomic status (Dabbs & Morris, 1990). And children who have a genetic predisposition to aggression are more likely to become aggressive if they are abused as children (Caspi et al., 2002). It seems that biological factors may predispose us to aggression, but that social factors act as triggers—a classic example of interactionism at work.

- 12214 reads