Each of the world’s economies can be viewed as operating somewhere on a spectrum between market capitalism and command socialism. In a market capitalist economy, resources are generally owned by private individuals who have the power to make decisions about their use. A market capitalist system is often referred to as a free enterprise economic system. In a command socialist economy, the government is the primary owner of capital and natural resources and has broad power to allocate the use of factors of production. Between these two categories lie mixed economies that combine elements of market capitalist and of command socialist economic systems.

No economy represents a pure case of either market capitalism or command socialism. To determine where an economy lies between these two types of systems, we evaluate the extent of government ownership of capital and natural resources and the degree to which government is involved in decisions about the use of factors of production.

Figure 2.12 below suggests the spectrum of economic systems. Market capitalist economies lie toward the left end of this spectrum; command socialist economies appear toward the right. Mixed economies lie in between. The market capitalist end of the spectrum includes countries such as the United States, the United Kingdom, and Chile. Hong Kong, though now part of China, has a long history as a market capitalist economy and is generally regarded as operating at the market capitalist end of the spectrum. Countries at the command socialist end of the spectrum include North Korea and Cuba.

Some European economies, such as France, Germany, and Sweden, have a sufficiently high degree of regulation that we consider them as operating more toward the center of the spectrum. Russia and China, which long operated at the command socialist end of the spectrum, can now be considered mixed economies. Most economies in Latin America once operated toward the right end of the spectrum. While their governments did not exercise the extensive ownership of capital and natural resources that are one characteristic of command socialist systems, their governments did impose extensive regulations. Many of these nations are in the process of carrying out economic reforms that will move them further in the direction of market capitalism.

The global shift toward market capitalist economic systems that occurred in the 1980s and 1990s was in large part the result of three important features of such economies. First, the emphasis on individual ownership and decision-making power has generally yielded greater individual freedom than has been available under command socialist or some more heavily regulated mixed economic systems that lie toward the command socialist end of the spectrum. People seeking political, religious, and economic freedom have thus gravitated toward market capitalism. Second, market economies are more likely than other systems to allocate resources on the basis of comparative advantage. They thus tend to generate higher levels of production and income than do other economic systems. Third, market capitalist-type systems appear to be the most conducive to entrepreneurial activity.

Suppose Christie Ryder had the same three plants we considered earlier in this chapter but was operating in a mixed economic system with extensive government regulation. In such a system, she might be prohibited from transferring resources from one use to another to achieve the gains possible from comparative advantage. If she were operating under a command socialist system, she would not be the owner of the plants and thus would be unlikely to profit from their efficient use. If that were the case, there is no reason to believe she would make any effort to assure the efficient use of the three plants. Generally speaking, it is economies toward the market capitalist end of the spectrum that offer the greatest inducement to allocate resources on the basis of comparative advantage. They tend to be more productive and to deliver higher material standards of living than do economies that operate at or near the command socialist end of the spectrum.

Market capitalist economies rely on economic freedom. Indeed, one way we can assess the degree to which a country can be considered market capitalist is by the degree of economic freedom it permits. Several organizations have attempted to compare economic freedom in various countries. One of the most extensive comparisons is a joint annual effort by the Heritage Foundation and The Wall Street Journal. The 2008 rating was based on policies in effect in 162 nations early that year. The report ranks these nations on the basis of such things as the degree of regulation of firms, tax levels, and restrictions on international trade. Hong Kong ranked as the freest economy in the world. North Korea received the dubious distinction of being the least free.

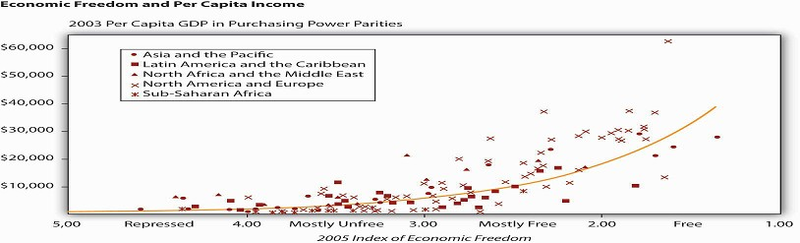

The horizontal axis shows the degree of economic freedom—“free,” “mostly free,” “mostly unfree,” and “repressed”—according to the measures used by the Heritage Foundation and The Wall Street Journal. The graph shows the relationship between economic freedom and per capita income. Countries with higher degrees of economic freedom tended to have higher per capita incomes.

Source: World Bank, World Development Indicators Online, available by subscription at www.worldbank.org/data; Central Intelligence Agency, The World Factbook 2004, available at http://www.cia.gov/cia/publications/factbook/index.html for the following countries: Bahamas, Burma, Cuba, Cyprus, Equatorial Guinea, North Korea, Libya, Qatar, Suriname, Taiwan, Zimbabwe; Marc A. Miles, Edwin J. Feulner, and Mary Anastasia O'Grady, 2005 Index of Economic Freedom (Washington, D.C.: The Heritage Foundation and Dow Jones & Company, Inc., 2005), at www.heritage.org/index.

It seems reasonable to expect that the greater the degree of economic freedom a country permits, the greater the amount of income per person it will generate. This proposition is illustrated in Figure 2.13

The group of countries categorized as “free” generated the highest incomes in the Heritage Foundation/ Wall Street Journal study; those rated as “repressed” had the lowest. The study also found that countries that over the last decade have done the most to improve their positions in the economic freedom rankings have also had the highest rates of growth. We must be wary of slipping into the fallacy of false cause by concluding from this evidence that economic freedom generates higher incomes. It could be that higher incomes lead nations to opt for greater economic freedom. But in this case, it seems reasonable to conclude that, in general, economic freedom does lead to higher incomes.

- 1533 reads