Common property resources 1 are resources for which no property rights have been defined. The difficulty with common property resources is that individuals may not have adequate incentives to engage in efforts to preserve or protect them. Consider, for example, the relative fates of cattle and buffalo in the United States in the nineteenth century. Cattle populations increased throughout the century, while the buffalo nearly became extinct. The chief difference between the two animals was that exclusive property rights existed for cattle but not for buffalo.

Owners of cattle had an incentive to maintain herd sizes. A cattle owner who slaughtered all of his or her cattle without providing for replacement of the herd would not have a source of future income. Cattle owners not only maintained their herds but also engaged in extensive efforts to breed high-quality livestock. They invested time and effort in the efficient management of the resource on which their livelihoods depended.

Buffalo hunters surely had similar concerns about the maintenance of buffalo herds, but they had no individual stake in doing anything about them—the animals were a common property resource. Thousands of individuals hunted buffalo for a living. Anyone who cut back on hunting in order to help to preserve the herd would lose income—and face the likelihood that other hunters would go on hunting at the same rate as before.

Today, exclusive rights to buffalo have been widely established. The demand for buffalo meat, which is lower in fat than beef, has been increasing, but the number of buffalo in the United States is rising rapidly. If buffalo were still a common property resource, that increased demand, in the absence of other restrictions on hunting of the animals, would surely result in the elimination of the animal. Because there are exclusive, transferable property rights in buffalo and because a competitive market brings buyers and sellers of buffalo and buffalo products together, we can be reasonably confident in the efficient management of the animal.

When a species is threatened with extinction, it is likely that no one has exclusive property rights to it. Whales, condors, grizzly bears, elephants in Central Africa—whatever the animal that is threatened —are common property resources. In such cases a government agency may impose limits on the killing of the animal or destruction of its habitat. Such limits can prevent the excessive private use of a common property resource. Alternatively, as was done in the case of the buffalo, private rights can be established, giving resource owners the task of preservation.

KEY TAKEAWAYS

- Public sector intervention to increase the level of provision of public goods may improve the efficiency of resource allocation by overcoming the problem of free riders.

- Activities that generate external costs are likely to be carried out at levels that exceed those that would be efficient; the public sector may seek to intervene to confront decision makers with the full costs of their choices.

- Some private activities generate external benefits.

- A common property resource is unlikely to be allocated efficiently in the marketplace.

TRY IT!

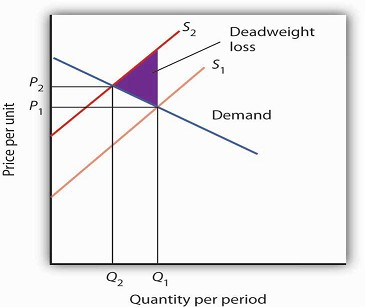

The manufacture of memory chips for computers generates pollutants that generally enter rivers and streams. Use the model of demand and supply to show the equilibrium price and output of chips. Assuming chip manufacturers do not have to pay the costs these pollutants impose, what can you say about the efficiency of the quantity of chips produced? Show the area of deadweight loss imposed by this external cost. Show how a requirement that firms pay these costs as they produce the chips would affect the equilibrium price and output of chips. Would such a requirement help to satisfy the efficiency condition? Explain.

Case in Point: Externalities and Smoking

© 2010 Jupiterimages Corporation

Smokers impose tremendous costs on themselves. Based solely on the degree to which smoking shortens their life expectancy, which is by about six years, the cost per pack is $35.64. That cost,

of course, is a private cost. In addition to that private cost, smokers impose costs on others. Those external costs come in three ways. First, they increase health-care costs and thus

increase health insurance premiums. Second, smoking causes fires that destroy more than $300 million worth of property each year. Third, more than 2,000 people die each year as a result of

“secondhand” smoke. A 1989 study by the RAND Corporation estimated these costs at $0.53 per pack.

In an important way, however, smokers also generate external benefits. They contribute to retirement programs and to Social Security, then die sooner than nonsmokers. They thus subsidize the

retirement programs of the rest of the population. According to the RAND study, that produces an external benefit of $0.24 per pack, leaving a net external cost of $0.29 per pack. Given that

state and federal excise taxes averaged $0.37 in 1989, the RAND researchers concluded that smokers more than paid their own way. Economists Jonathan Gruber of the Massachusetts Institute of

Technology and Botond Koszegi of the University of California at Berkeley have suggested that, in the case of people who consume “addictive bads” such as cigarettes, an excise tax on

cigarettes of as much as $4.76 per pack may improve the welfare of smokers.

They base their argument on the concept of “time inconsistency,” which is the theory that smokers seek the immediate gratification of a cigarette and then regret their decision later.

Professors Gruber and Koszegi argue that higher taxes would serve to reduce the quantity of cigarettes demanded and thus reduce behavior that smokers would otherwise regret. Their argument is

that smokers impose “internalities” on themselves and that higher taxes would reduce this.

Where does this lead us? If smokers are “rationally addicted” to smoking, i.e., they have weighed the benefits and costs of smoking and have chosen to smoke, then the only problem for public

policy is to assure that smokers are confronted with the external costs they impose. In that case, the problem is solved: through excise taxes, smokers more than pay their own way. But, if

the decision to smoke is an irrational one, it may be improved through higher excise taxes on smoking.

Sources: Jonathan Gruber and Botond Koszegi, “A Theory of Government Regulation of Addictive Bads: Optimal Tax Levels and Tax Incidence for Cigarette Excise Taxation,” NBER Working Paper

8777, February 2002; Willard G. Manning et al., “The Taxes of Sin: Do Smokers and Drinkers Pay Their Way?” Journal of the American Medical Association, 261 (March 17, 1989): 1604–1609.

ANSWER TO TRY IT! PROBLEM

In the absence of any regulation, chip producers are not faced with the costs of the pollution their operations generate. The market price is thus P1 and the quantity Q1. The efficiency

condition is not met; the price is lower and the quantity greater than would be efficient. If producers were forced to face the cost of their pollution as well as other production costs, the

supply curve would shift to S2, the price would rise to P2, and the quantity would fall to Q2. The new solution satisfies the efficiency condition.

- 3783 reads