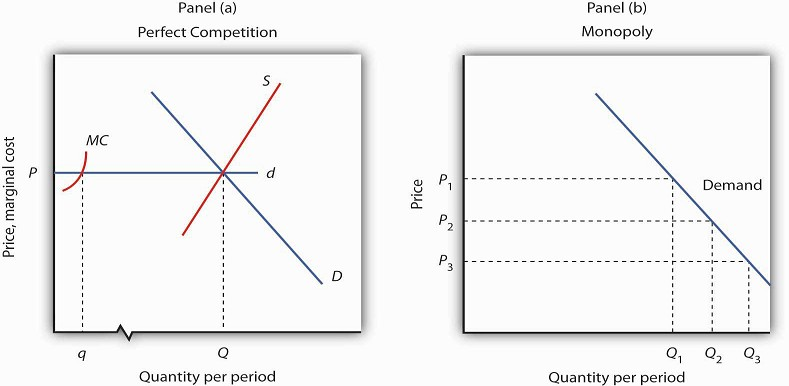

Because a monopoly firm has its market all to itself, it faces the market demand curve. Figure 10.2 compares the demand situations faced by a monopoly and a perfectly competitive firm. In Panel (a), the equilibrium price for a perfectly competitive firm is determined by the intersection of the demand and supply curves. The market supply curve is found simply by summing the supply curves of individual firms. Those, in turn, consist of the portions of marginal cost curves that lie above the average variable cost curves. The marginal cost curve, MC, for a single firm is illustrated. Notice the break in the horizontal axis indicating that the quantity produced by a single firm is a trivially small fraction of the whole. In the perfectly competitive model, one firm has nothing to do with the determination of the market price. Each firm in a perfectly competitive industry faces a horizontal demand curve defined by the market price.

Panel (a) shows the determination of equilibrium price and output in a perfectly competitive market. A typical firm with marginal cost curve MC is a price taker, choosing to produce quantity q at the equilibrium price P. In Panel (b) a monopoly faces a downward-sloping market demand curve. As a profit maximizer, it determines its profitmaximizing output. Once it determines that quantity, however, the price at which it can sell that output is found from the demand curve. The monopoly firm can sell additional units only by lowering price. The perfectly competitive firm, by contrast, can sell any quantity it wants at the market price.

Contrast the situation shown in Panel (a) with the one faced by the monopoly firm in Panel (b). Because it is the only supplier in the industry, the monopolist faces the downward-sloping market demand curve alone. It may choose to produce any quantity. But, unlike the perfectly competitive firm, which can sell all it wants at the going market price, a monopolist can sell a greater quantity only by cutting its price.

Suppose, for example, that a monopoly firm can sell quantity Q1 units at a price P1 in Panel (b). If it wants to increase its output to Q2 units—and sell that quantity—it must reduce its price to P2. To sell quantity Q3 it would have to reduce the price to P3. The monopoly firm may choose its price and output, but it is restricted to a combination of price and output that lies on the demand curve. It could not, for example, charge price P1 and sell quantity Q3. To be a price setter, a firm must face a downwardsloping demand curve.

- 2139 reads