The long-run equilibrium solution in monopolistic competition always produces zero economic profit at a point to the left of the minimum of the average total cost curve. That is because the zero profit solution occurs at the point where the downward-sloping demand curve is tangent to the average total cost curve, and thus the average total cost curve is itself downward-sloping. By expanding output, the firm could lower average total cost. The firm thus produces less than the output at which it would minimize average total cost. A firm that operates to the left of the lowest point on its average total cost curve has excess capacity.

Because monopolistically competitive firms charge prices that exceed marginal cost, monopolistic competition is inefficient. The marginal benefit consumers receive from an additional unit of the good is given by its price. Since the benefit of an additional unit of output is greater than the marginal cost, consumers would be better off if output were expanded. Furthermore, an expansion of output would reduce average total cost. But monopolistically competitive firms will not voluntarily increase output, since for them, the marginal revenue would be less than the marginal cost.

One can thus criticize a monopolistically competitive industry for falling short of the efficiency standards of perfect competition. But monopolistic competition is inefficient because of product differentiation. Think about a monopolistically competitive activity in your area. Would consumers be better off if all the firms in this industry produced identical products so that they could match the assumptions of perfect competition? If identical products were impossible, would consumers be better off if some of the firms were ordered to shut down on grounds the model predicts there will be “too many” firms? The inefficiency of monopolistic competition may be a small price to pay for a wide range of product choices. Furthermore, remember that perfect competition is merely a model. It is not a goal toward which an economy might strive as an alternative to monopolistic competition.

KEY TAKEAWAYS

- A monopolistically competitive industry features some of the same characteristics as perfect competition: a large number of firms and easy entry and exit.

- The characteristic that distinguishes monopolistic competition from perfect competition is differentiated products; each firm is a price setter and thus faces a downward-sloping demand curve.

- Short-run equilibrium for a monopolistically competitive firm is identical to that of a monopoly firm. The firm produces an output at which marginal revenue equals marginal cost and sets its price according to its demand curve.

- In the long run in monopolistic competition any economic profits or losses will be eliminated by entry or by exit, leaving firms with zero economic profit.

- A monopolistically competitive industry will have some excess capacity; this may be viewed as the cost of the product diversity that this market structure produces.

TRY IT!

Suppose the monopolistically competitive restaurant industry in your town is in long-run equilibrium, when difficulties in hiring cause restaurants to offer higher wages to cooks, servers, and dishwashers. Using graphs similar to Figure 11.1 and Figure 11.2, explain the effect of the wage increase on the industry in the short run and in the long run. Be sure to include in your answer an explanation of what happens to price, output, and economic profit.

Case in Point: Craft Brewers: The Rebirth of a Monopolistically Competitive Industry

In the early 1900s, there were about 2,000 local beer breweries across America. Prohibition in the 1920s squashed the industry; after the repeal of Prohibition, economies of scale eliminated

smaller breweries. By the early 1980s only about 40 remained in existence.

But the American desire for more variety has led to the rebirth of the nearly defunct industry. To be sure, large, national beer companies dominated the overall ale market in 1980 and they

still do today, with 43 large national and regional breweries sharing about 85% of the U.S. market for beer. But their emphasis on similarly tasting, light lagers (at least, until they felt

threatened enough by the new craft brewers to come up with their own specialty brands) left many niches to be filled. One niche was filled by imports, accounting for about 12% of the U.S.

market. That leaves 3 to 4% of the national market for the domestic specialty or “craft” brewers.

The new craft brewers, which include contract brewers, regional specialty brewers, microbreweries, and brewpubs, offer choice. As Neal Leathers at Big Sky Brewing Company in Missoula, Montana

put it, “We sort of convert people. If you haven’t had very many choices, and all of a sudden you get choices—especially if those choices involve a lot of flavor and quality—it’s hard to go

back.”

Aided by the recent legalization in most states of brewpubs, establishments where beers are manufactured and retailed on the same premises, the number of microbreweries grew substantially

over the last 25 years. A recent telephone book in Colorado Springs, a city with a population of about a half million and the home of the authors of your textbook, listed nine microbreweries

and brewpubs; more exist, but prefer to be listed as restaurants.

To what extent does this industry conform to the model of monopolistic competition? Clearly, the microbreweries sell differentiated products, giving them some degree of price-setting power. A

sample of four brewpubs in the downtown area of Colorado Springs revealed that the price of a house beer ranged from 13 to 22 cents per ounce.

Entry into the industry seems fairly easy, judging from the phenomenal growth of the industry. After more than a decade of explosive growth and then a period of leveling off, the number of

craft breweries, as they are referred to by the Association of Brewers, stood at 1,463 in 2007. The start-up cost ranges from $100,000 to $400,000, according to Kevin Head, the owner of the

Rhino Bar, also in Missoula.

The monopolistically competitive model also predicts that while firms can earn positive economic profits in the short run, entry of new firms will shift the demand curve facing each firm to

the left and economic profits will fall toward zero. Some firms will exit as competitors win customers away from them. In the combined microbrewery and brewpub sub-sectors of the craft beer

industry in 2007, for example, there were 94 openings and 51 closings.

Sources: Jim Ludwick, “The Art of Zymurgy—It’s the Latest Thing: Microbrewers are Tapping into the New Specialty Beer Market,” Missoulian

ANSWER TO TRY IT! PROBLEM

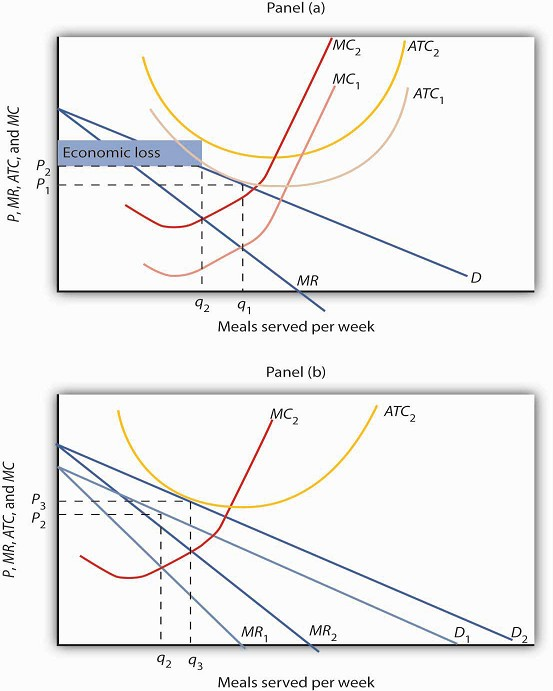

As shown in Panel (a), higher wages would cause both MC and ATC to increase. The upward shift in MC from MC1 to MC2 would cause the profit-maximizing level of output (number of meals served

per week, in this case) to fall from q1 to q2 and price to increase from P1 to P2. The increase in ATC from ATC1 to ATC2 would mean that some restaurants would be earning negative economic

profits, as shown by the shaded area.

As shown in Panel (b), in the long run, as some restaurants close down, the demand curve faced by the typical remaining restaurant would shift to the right from D to D’. The demand curve

shift leads to a corresponding shift in marginal revenue from MR to MR1. Price would increase further from P2 to P3, and output would increase to q3, above q2. In the new long-run

equilibrium, restaurants would again be earning zero economic profit.

- 4705 reads