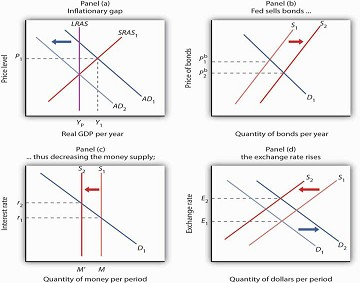

The Fed will generally pursue a contractionary monetary policy when it considers inflation a threat.Suppose, for example, that the economy faces an inflationary gap; the aggregate demand and short-run aggregate supply curves intersect to the right of the long-run aggregate supply curve, as shown in Panel (a) of Figure 26.2.

In Panel (a), the economy has an inflationary gap Y1 − YP. A contractionary monetary policy could seek to close this gap by shifting the aggregate demand curve to AD2. In Panel (b), the Fed sells bonds, shifting the supply curve for bonds to S2 and lowering the price of bonds to Pb 2. The lower price of bonds means a higher interest rate, r2, as shown in Panel (c). The higher interest rate also increases the demand for and decreases the supply of dollars, raising the exchange rate to E2 in Panel (d), which will increase net exports. The decreases in investment and net exports are responsible for decreasing aggregate demand in Panel (a).

To carry out a contractionary policy, the Fed sells bonds. In the bond market, shown in Panel (b) of Figure 26.2, the supply curve shifts to the right, lowering the price of bonds and increasing the interest rate. In the money market, shown in Panel (c), the Fed’s bond sales reduce the money supply and raise the interest rate. The higher interest rate reduces investment. The higher interest rate also induces a greater demand for dollars as foreigners seek to take advantage of higher interest rates in the United States. The supply of dollars falls; people in the United States are less likely to purchase foreign interestearning assets now that U.S. assets are paying a higher rate. These changes boost the exchange rate, as

shown in Panel (d), which reduces exports and increases imports and thus causes net exports to fall.The contractionary monetary policy thus shifts aggregate demand to the left, by an amount equal to the multiplier times the combined initial changes in investment and net exports, as shown in Panel (a).

KEY TAKEAWAYS

- The Federal Reserve Board and the Federal Open Market Committee are among the most powerful institutions in the United States.

- The Fed’s primary goal appears to be the control of inflation. Providing that inflation is under control, the Fed will act to close recessionary gaps.

- Expansionary policy, such as a purchase of government securities by the Fed, tends to push bond prices up and interest rates down, increasing investment and aggregate demand. Contractionary policy, such as a sale of government securities by the Fed, pushes bond prices down, interest rates up, investment down, and aggregate demand shifts to the left.

TRY IT!

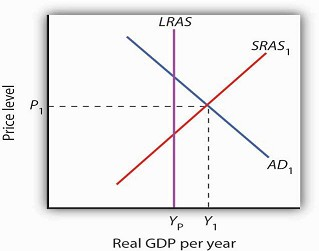

The figure shows an economy operating at a real GDP of Y1 and a price level of P1, at the intersection of AD1 and SRAS1.

- What kind of gap is the economy experiencing?

- What type of monetary policy (expansionary or contractionary) would be appropriate for closing the gap?

- If the Fed decided to pursue this policy, what type of open-market operations would it conduct?

- How would bond prices, interest rates, and the exchange rate change?

- How would investment and net exports change?

- How would the aggregate demand curve shift?

Case in Point: A Brief History of the Greenspan Fed

With the passage of time and the fact that the fallout on the economy turned out to be relatively minor, it is hard in retrospect to realize how scary a situation Alan Greenspan and the Fed

faced just two months after his appointment as Chairman of the Federal Reserve Board. On October 12, 1987, the stock market had its worst day ever. The Dow Jones Industrial Average plunged

508 points, wiping out more than $500 billion in a few hours of feverish trading on Wall Street. That drop represented a loss in value of over 22%. In comparison, the largest daily drop in

2008 of 778 points on September 29, 2008, represented a loss in value of about 7%.

When the Fed faced another huge plunge in stock prices in 1929—also in October—members of the Board of Governors met and decided that no action was necessary. Determined not to repeat the

terrible mistake of 1929, one that helped to usher in the Great Depression, Alan Greenspan immediately reassured the country, saying that the Fed would provide adequate liquidity, by buying

federal securities, to assure that economic activity would not fall. As it turned out, the damage to the economy was minor and the stock market quickly regained value.

In the fall of 1990, the economy began to slip into recession. The Fed responded with expansionary monetary policy—cutting reserve requirements, lowering the discount rate, and buying

Treasury bonds.

Interest rates fell quite quickly in response to the Fed’s actions, but, as is often the case, changes to the components of aggregate demand were slower in coming. Consumption and investment

began to rise in 1991,but their growth was weak, and unemployment continued to rise because growth in output was too slow to keep up with growth in the labor force. It was not until the fall

of 1992 that the economy started to pick up steam. This episode demonstrates an important difficulty with stabilization policy: attempts to manipulate aggregate demand achieve shifts in the

curve, but with a lag.

Throughout the rest of the 1990s, with some tightening when the economy seemed to be moving into an inflationary gap and some loosening when the economy seemed to be possibly moving toward a

recessionary gap—especially in 1998 and 1999 when parts of Asia experienced financial turmoil and recession and European growth had slowed down—the Fed helped steer what is now referred to as

the Goldilocks (not too hot, not too cold, just right) economy.

The U.S. economy again experienced a mild recession in 2001 under Greenspan. At that time, the Fed systematically conducted expansionary policy. Similar to its response to the 1987 stock

market crash, the Fed has been credited with maintaining liquidity following the dot-com stock market crash in early 2001 and the attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon in

September 2001.

When Greenspan retired in January 2006, many hailed him as the greatest central banker ever. As the economy faltered in 2008 and as the financial crisis unfolded throughout the year, however,

the question of how the policies of Greenspan’s Fed played into the current difficulties took center stage. Testifying before Congress in October 2008, he said that the country faces a

“once-in-a-century credit tsunami,” and he admitted, “I made a mistake in presuming that the self-interests of organizations, specifically banks and others, were such as that they were best

capable of protecting their own shareholders and their equity in their firms.” The criticisms he has faced are twofold: that the very low interest rates used to fight the 2001 recession and

maintained for too long fueled the real estate bubble and that he did not promote appropriate regulations to deal with the new financial instruments that were created in the early 2000s.

While supporting some additional regulations when he testified before Congress, he also warned that overreacting could be dangerous: “We have to recognize that this is almost surely a

once-in-a-century phenomenon, and, in that regard, to realize the types of regulation that would prevent this from happening in the future are so onerous as to basically suppressthe growth

rate in the economy and . . . the standards of living of the American people.”

ANSWERS TO TRY IT! PROBLEMS

- Inflationary gap

- Contractionary

- Open-market sales of bonds

- The price of bonds would fall. The interest rate and the exchange rate would rise.

- Investment and net exports would fall.

- The aggregate demand curve would shift to the left.

- 15756 reads