When Richard Nixon became president in 1969, he faced a very different economic situation than the one that had confronted John Kennedy eight years earlier. The economy had clearly pushed beyond full employment; the unemployment rate had plunged to 3.6% in 1968. Inflation, measured using the implicit price deflator, had soared to 4.3%, the highest rate that had been recorded since 1951. The economy needed a cooling off. Nixon, the Fed, and the economy’s own process of self-correction delivered it.

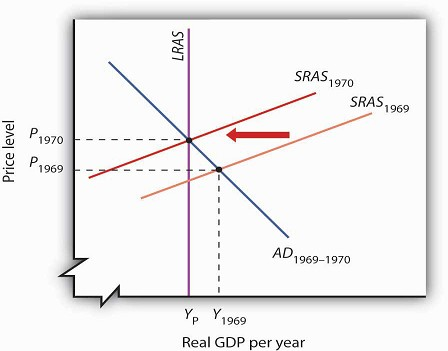

Figure 32.5 tells the story—it is a simple one. The economy in 1969 was in an inflationary gap. It had been in such a gap for years, but this time policy makers were no longer forcing increases in aggregate demand to keep it there. The adjustment in short-run aggregate supply brought the economy back to its potential output.

The Nixon administration and the Fed joined to end the expansionary policies that had prevailed in the 1960s, so that aggregate demand did not rise in 1970, but the short-run aggregate supply curve shifted to the left as the economy responded to an inflationary gap.

But what we can see now as a simple adjustment seemed anything but simple in 1970. Economists did not think in terms of shifts in short-run aggregate supply. Keynesian economics focused on shifts in aggregate demand, not supply.

For the Nixon administration, the slump in real GDP in 1970 was a recession, albeit an odd one. The price level had risen sharply. That was not, according to the Keynesian story, supposed to happen; there was simply no reason to expect the price level to soar when real GDP and employment were falling.

The administration dealt with the recession by shifting to an expansionary fiscal policy. By 1973, the economy was again in an inflationary gap. The economy’s 1974 adjustment to the gap came with another jolt. The Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) tripled the price of oil. The resulting shift to the left in short-run aggregate supply gave the economy another recession and another jump in the price level.

The second half of the decade was, in some respects, a repeat of the first. The administrations of Gerald Ford and then Jimmy Carter, along with the Fed, pursued expansionary policies to stimulate the economy. Those helped boost output, but they also pushed up prices. As we saw in the chapter on inflation and unemployment, inflation and unemployment followed a cycle to higher and higher levels.

The 1970s presented a challenge not just to policy makers, but to economists as well. The sharp changes in real GDP and in the price level could not be explained by a Keynesian analysis that focused on aggregate demand. Something else was happening. As economists grappled to explain it, their efforts would produce the model with which we have been dealing and around which a broad consensus of economists has emerged.But, before that consensus was to come, two additional elements of the puzzle had to be added. The first was the recognition of the importance of monetary policy. The second was the recognition of the role of aggregate supply, both in the long and in the short run.

- 1634 reads