Ceilings mean that suppliers cannot legally charge more than a specific price. Limits on apartment rents are one form of ceiling. In times of emergency – such as flooding or famine, price controls are frequently imposed on foodstuffs, in conjunction with rationing, to ensure that access is not determined by who has the most income. The problem with price ceilings, however, is that they leave demand unsatisfied, and therefore they must be accompanied by some other allocation mechanism.

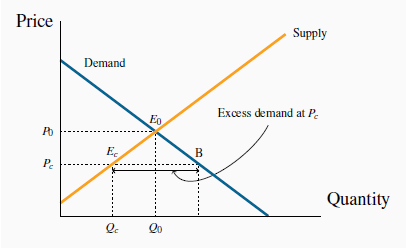

Consider an environment where, for some reason – perhaps a sudden and unanticipated growth in population – rents increase. Let the resulting equilibrium be defined by the point Eo in Figure 3.6. If the government were to decide that this is an unfair price because it places hardships on low- and middle-income households, it might impose a price limit, or ceiling, of Pc. The problem with such a limit is that excess demand results: Individuals want to rent more apartments than are available in the city. In a free market the price would adjust upward to eliminate the excess demand, but in this controlled environment it cannot. So some other way of allocating the available supply between demanders must evolve.

In reality, most apartments are allocated to those households already occupying them. But what happens when such a resident household decides to purchase a home or move to another city? It holds a valuable asset, since the price/rent it is paying is less than the free-market price. Rather than give this surplus value to another family, it might decide to sublet at a price above what it currently pays. While this might be illegal, the family knows that there is excess demand and therefore such a solution is possible. A variation on this outcome is for an incoming tenant to pay money, sometimes directly to an existing tenant or to the building superintendent, or possibly to a real estate broker who will “buy out” existing tenants. This is called “key money.”

Rent controls are widely studied in economics, and the consequences are well understood: Landlordstend not to repair or maintain their rental units and so the residential stock deteriorates. Builders realize that more money is to be made in building condominium units, or in converting rental units to condominiums. The frequent consequence is a reduction in supply and a reduced quality. Market forces are hard to circumvent because, as we emphasized in Chapter 1, economic players react to the incentives they face. This is an example of what we call the law of unintended consequences.

- 3853 reads