Externalities of the positive kind enable individuals or producers to get a type of ‘free ride’ on the efforts of others. Real world examples abound: When a large segment of the population is inoculated against disease, the remaining individuals benefit on account of the reduced probability of transmission.

A less well recognized example is the benefit derived by many Canadian firms from research and development (R&D) undertaken in the United States. Professor Dan Treffler of the University of Toronto has documented the positive spillover effects in detail. Canadian firms, and firms in many other economies, learn from the research efforts of U.S. firms that invest heavily in R&D. In the same vein, universities and research institutes open up new fields of knowledge, with the result that society at large, and sometimes the corporate sector, gain from this enhanced understanding of science, the environment, or social behaviours.

The free market may not cope any better with these positive externalities than it does with negative externalities, and government intervention may be beneficial. For example, firms that invest heavily in research and development would not undertake such investment if competitors couldhave a complete free ride and appropriate the fruits. This is why patent laws exist, as we shall see later in discussing Canada’s competition policy. These laws prevent competitors from copying the product development of firms that invest in R&D. If such protection were not in place, firms would not allocate sufficient resources to R&D, which is a real engine of economic growth. In essence, the economy’s research-directed resources would not be appropriately rewarded, and thus too little research would take place.

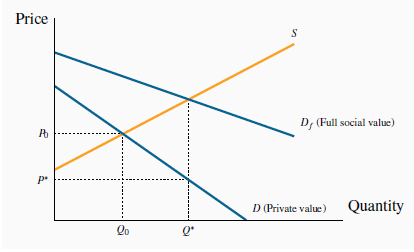

While patent protection is one form of corrective action, subsidies are another. We illustrated above that an appropriately formulated tax on a good that creates negative externalities can reduce demand for that good, and thereby reduce pollution. A subsidy can be thought of as a negative tax. Consider the example in Figure 5.6.

The value to society of vaccinations exceeds the value to individuals: the greater the number of individuals vaccinated, the lower is the probability of others contracting the

virus.  reflects this additional value. Consequently, the

social optimum is Q* which exceeds

reflects this additional value. Consequently, the

social optimum is Q* which exceeds  .

.

Individuals have a demand for flu shots given by D. This reflects their private valuation – their personal willingness to pay. But the social value of flu shots is greater. When a given number of individuals are inoculated, the probability that others will be infected falls. Additionally, with higher rates of inoculation, the health system will incur fewer costs in treating the infected. Therefore, the value to society of any quantity of flu shots is greater than the sum of the values that individuals place on them.

Let  reflects the full social value of any quantity of flu

shots. If S is the supply curve, the socially optimal, efficient, market outcome is Q*. How can we influence the market to move from

reflects the full social value of any quantity of flu

shots. If S is the supply curve, the socially optimal, efficient, market outcome is Q*. How can we influence the market to move from  to Q*? One solution is a subsidy that would reduce the price from

to Q*? One solution is a subsidy that would reduce the price from  to P*. Rather than shifting the supply curve upwards, as a tax does, the subsidy

would shift the supply downward, sufficiently to intersect D at the output Q*. In some real world examples, the value of the positive externality is so great that the government may decide to

drive the price to zero, and thereby provide the inoculation at a zero price. For example, children typically get their MMR shots (measles, mumps, and rubella) free of charge.

to P*. Rather than shifting the supply curve upwards, as a tax does, the subsidy

would shift the supply downward, sufficiently to intersect D at the output Q*. In some real world examples, the value of the positive externality is so great that the government may decide to

drive the price to zero, and thereby provide the inoculation at a zero price. For example, children typically get their MMR shots (measles, mumps, and rubella) free of charge.

- 3908 reads