A third reason that monopolistic companies continue to survive is that they are successful in preventing the entry of new firms and products. Patents and copyrights are one vehicle for preserving the sole-supplier role, and are certainly necessary to encourage firms to undertake the research and development (R&D) for new products.

While copyright protection is legal, predatory pricing is an illegal form of entry barrier, and we explore it more fully in Government. An example would be where an existing firm that sells nationally may deliberately undercut the price of a would-be local entrant to the industry. Airlines with a national scope are frequently accused of posting low fares on flights in regional markets that a new carrier is trying to enter.

Political lobbying is another means of maintaining monopolistic power. For example, the Canadian

Wheat Board had fought successfully for decades to prevent independent farmers from marketing wheat. This Board lost it’s monopoly status in August 2012, when the government of the day decided it was not beneficial to consumers or farmers in general.

Critical networks also form a type of barrier, though not always a monopoly. The compression software WinZip benefits from the fact that it is used almost universally. There are many free compression programs available on the internet. But WinZip can charge for its product because virtually everybody uses it. Free network products that no one uses are worth very little, even if they come at zero cost.

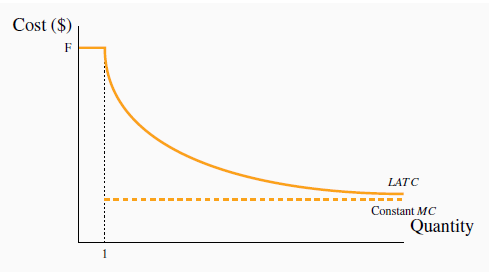

Many large corporations produce products that require a large up-front investment; this might be in the form of research and development, or the construction of costly production facilities. For example, Boeing or Airbus incurs billions of dollars in developing their planes; pharmaceuticals may have to invest a billion dollars to develop a new drug. However, once such an investment is complete, the cost of producing each unit of output may be constant. Such a phenomenon is displayed in Figure 10.2. In this case the average cost for a small number of units produced is high, but once the fixed cost is spread over an ever larger output, the average cost declines, and in the limit approaches the marginal cost. These production structures are common in today’s global economy, and they give rise to markets characterized either by a single supplier or a small number of suppliers.

With a fixed cost of producing the first unit of output equal to F and a constant marginal cost thereafter, the long run average total cost, LATC, declines indefinitely and becomes asymptotic to the marginal cost curve.

This figure is also useful in understanding the role of patents. Suppose that Pharma A spends one billion dollars in developing a new drug and has constant unit production costs thereafter, while Pharma B avoids research and development and simply imitates Pharma A’s product. Clearly Pharma B would have a LATC equal to its LMC, and would be able to undercut the initial developer of the drug. Such an outcome would discourage investment in new products and the economy at large would suffer as a consequence.

- 2170 reads