Suppose a private firm, Terror Alert, Inc., develops a completely reliable system to identify and intercept 98% of any would-be terrorists that might attempt to enter the United States from anywhere in the world. This service is a public good. Once it is provided, no one can be excluded from the system’s protection on grounds that he or she has not paid for it, and the cost of adding one more person to the group protected is zero. Suppose that the system, by eliminating a potential threat to U.S. security, makes the average person in the United States better off; the benefit to each household from the added security is worth $40 per month (about the same as an earthquake insurance premium). There are roughly 113 million households in the United States, so the total benefit of the system is $4.5 billion per month. Assume that it will cost Terror Alert, Inc., $1 billion per month to operate. The benefits of the system far outweigh the cost.

Suppose that Terror Alert installs its system and sends a bill to each household for $20 for the first month of service—an amount equal to half of each household’s benefit. If each household pays its bill, Terror Alert will enjoy a tidy profit; it will receive revenues of more than $2.25 billion per month.

But will each household pay? Once the system is in place, each household would recognize that it will benefit from the security provided by Terror Alert whether it pays its bill or not. Although some households will voluntarily pay their bills, it seems unlikely that very many will. Recognizing the opportunity to consume the good without paying for it, most would be free riders. Free riders are people or firms that consume a public good without paying for it. Even though the total benefit of the system is $4.5 billion, Terror Alert will not be faced by the marketplace with a signal that suggests that the system is worthwhile. It is unlikely that it will recover its cost of $1 billion per month. Terror Alert is not likely to get off the ground.

The bill for $20 from Terror Alert sends the wrong signal, too. An efficient market requires a price equal to marginal cost. But the marginal cost of protecting one more household is zero; adding one more household adds nothing to the cost of the system. A household that decides not to pay Terror Alert anything for its service is paying a price equal to its marginal cost. But doing that, being a free rider, is precisely what prevents Terror Alert from operating.

Because no household can be excluded and because the cost of an extra household is zero, the efficiency condition will not be met in a private market. What is true of Terror Alert, Inc., is true of public goods in general: they simply do not lend themselves to private market provision.

Public Goods and the Government

Because many individuals who benefit from public goods will not pay for them, private firms will produce a smaller quantity of public goods than is efficient, if they produce them at all. In such cases, it may be desirable for government agencies to step in. Government can supply a greater quantity of the good by direct provision, by purchasing the public good from a private agency, or by subsidizing consumption. In any case, the cost is financed through taxation and thus avoids the free-rider problem.

Most public goods are provided directly by government agencies. Governments produce national defense and law enforcement, for example. Private firms under contract with government agencies produce some public goods. Park maintenance and fire services are public goods that are sometimes produced by private firms. In other cases, the government promotes the private consumption or production of public goods by subsidizing them. Private charitable contributions often support activities that are public goods; federal and state governments subsidize these by allowing taxpayers to reduce their tax payments by a fraction of the amount they contribute.

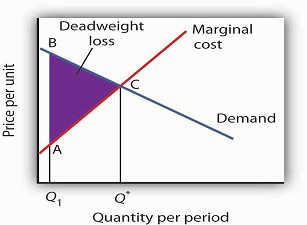

Because free riders will prevent firms from being able to require consumers to pay for the benefits received from consuming a public good, output will be less than the efficient level. In the case shown here, private donations achieved a level of the public good of Q1 per period. The efficient level is Q*. The deadweight loss is shown by the triangle ABC.

While the market will produce some level of public goods in the absence of government intervention, we do not expect that it will produce the quantity that maximizes net benefit. Figure 6.11 illustrates the problem. Suppose that provision of a public good such as national defense is left entirely to private firms. It is likely that some defense services would be produced; suppose that equals Q1 units per period. This level of national defense might be achieved through individual contributions. But it is very unlikely that contributions would achieve the correct level of defense services. The efficient quantity occurs where the demand, or marginal benefit, curve intersects the marginal cost curve, at Q*. The deadweight loss is the shaded area ABC; we can think of this as the net benefit of government intervention to increase the production of national defense from Q1 up to the efficient quantity, Q*.

Heads Up!

Note that the definitions of public and private goods are based on characteristics of the goods themselves, not on whether they are provided by the public or the private sector. Postal services are a private good provided by the public sector. The fact that these goods are produced by a government agency does not make them a public good.

- 3061 reads