Suppose that in the course of production, the firms in a particular industry generate air pollution. These firms thus impose costs on others, but they do so outside the context of any market exchange—no agreement has been made between the firms and the people affected by the pollution. The firms thus will not be faced with the costs of their action. A cost imposed on others outside of any market exchange is an external cost.

We saw an example of an external cost in our imaginary decision to go for a drive. Here is another: violence on television, in the movies, and in video games. Many critics argue that the violence that pervades these media fosters greater violence in the real world. By the time a child who spends the average amount of time watching television finishes elementary school, he or she will have seen 100,000 acts of violence, including 8,000 murders, according to the American Psychological Association. Thousands of studies of the relationship between violence in the media and behavior have concluded that there is a link between watching violence and violent behaviors. Video games are a major element of the problem, as young children now spend hours each week playing them. Fifty percent of fourth-grade graders say that their favorite video games are the “first person shooter” type. 1

Any tendency of increased violence resulting from increased violence in the media constitutes an external cost of such media. The American Academy of Pediatrics reported in 2001 that homicides were the fourth leading cause of death among children between the ages of 10 and 14 and the second leading cause of death for people aged 15 to 24 and has recommended a reduction in exposure to media violence. 2 It seems reasonable to assume that at least some of these acts of violence can be considered an external cost of violence in the media.

An action taken by a person or firm can also create benefits for others, again in the absence of any market agreement; such a benefit is called an external benefit. A firm that builds a beautiful building generates benefits to everyone who admires it; such benefits are external.

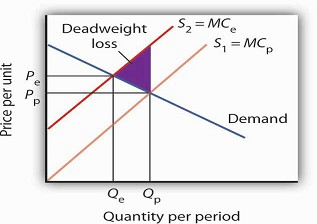

When firms in an industry generate external costs, the supply curve S1 reflects only their private marginal costs, MCP. Forcing firms to pay the external costs they impose shifts the supply curve to S2, which reflects the full marginal cost of the firms’ production, MCe. Output is reduced and price goes up. The deadweight loss that occurs when firms are not faced with the full costs of their decisions is shown by the shaded area in the graph.

External Costs and Efficiency

The case of the polluting firms is illustrated in Figure 6.12. The industry supply curve S1 reflects private marginal costs, MCp. The market price is Pp for a quantity Qp. This is the solution that would occur if firms generating external costs were not forced to pay those costs. If the external costs generated by the pollution were added, the new supply curve S2 would reflect higher marginal costs, MCe. Faced with those costs, the market would generate a lower equilibrium quantity, Qe. That quantity would command a higher price, Pe. The failure to confront producers with the cost of their pollution means that consumers do not pay the full cost of the good they are purchasing. The level of output and the level of pollution are therefore higher than would be economically efficient. If a way could be found to confront producers with the full cost of their choices, then consumers would be faced with a higher cost as well. Figure 6.12 shows that consumption would be reduced to the efficient level, Qe, at which demand and the full marginal cost curve (MCe) intersect. The deadweight loss generated by allowing the external cost to be generated with an output of Qp is given as the shaded region in the graph.

- 2697 reads