Oligopoly presents a problem in which decision makers must select strategies by taking into account the responses of their rivals, which they cannot know for sure in advance. The Start Up feature at the beginning of this chapter suggested the uncertainty eBay faces as it considers the possibility of competition from Google. A choice based on the recognition that the actions of others will affect the outcome of the choice and that takes these possible actions into account is called a strategic choice. Game theory is an analytical approach through which strategic choices can be assessed.

Among the strategic choices available to an oligopoly firm are pricing choices, marketing strategies, and product-development efforts. An airline’s decision to raise or lower its fares—or to leave them unchanged—is a strategic choice. The other airlines’ decision to match or ignore their rival’s price decision is also a strategic choice. IBM boosted its share in the highly competitive personal computer market in large part because a strategic product-development strategy accelerated the firm’s introduction of new products.

Once a firm implements a strategic decision, there will be an outcome. The outcome of a strategic decision is called a payoff. In general, the payoff in an oligopoly game is the change in economic profit to each firm. The firm’s payoff depends partly on the strategic choice it makes and partly on the strategic choices of its rivals. Some firms in the airline industry, for example, raised their fares in 2005, expecting to enjoy increased profits as a result. They changed their strategic choices when other airlines chose to slash their fares, and all firms ended up with a payoff of lower profits—many went into bankruptcy.

We shall use two applications to examine the basic concepts of game theory. The first examines a classic game theory problem called the prisoners’ dilemma. The second deals with strategic choices by two firms in a duopoly.

The Prisoners’ Dilemma

Suppose a local district attorney (DA) is certain that two individuals, Frankie and Johnny, have committed a burglary, but she has no evidence that would be admissible in court.

The DA arrests the two. On being searched, each is discovered to have a small amount of cocaine. The DA now has a sure conviction on a possession of cocaine charge, but she will get a conviction on the burglary charge only if at least one of the prisoners confesses and implicates the other.

The DA decides on a strategy designed to elicit confessions. She separates the two prisoners and then offers each the following deal: “If you confess and your partner doesn’t, you will get the minimum sentence of one year in jail on the possession and burglary charges. If you both confess, your sentence will be three years in jail. If your partner confesses and you do not, the plea bargain is off and you will get six years in prison. If neither of you confesses, you will each get two years in prison on the drug charge.”

The two prisoners each face a dilemma; they can choose to confess or not confess. Because the prisoners are separated, they cannot plot a joint strategy. Each must make a strategic choice in isolation.

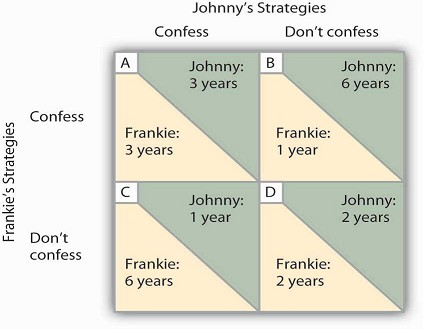

The outcomes of these strategic choices, as outlined by the DA, depend on the strategic choice made by the other prisoner. The payoff matrix for this game is given in Figure 11.5. The two rows represent Frankie’s strategic choices; she may confess or not confess. The two columns represent Johnny’sstrategic choices; he may confess or not confess. There are four possible outcomes: Frankie and Johnny both confess (cell A), Frankie confesses but Johnny does not (cell B), Frankie does not confess but Johnny does (cell C), and neither Frankie nor Johnny confesses (cell D). The portion at the lower left in each cell shows Frankie’s payoff; the shaded portion at the upper right shows Johnny’s payoff.

If Johnny confesses, Frankie’s best choice is to confess—she will get a three-year sentence rather than the six-year sentence she would get if she did not confess. If Johnny does not confess, Frankie’s best strategy is still to confess—she will get a oneyear rather than a two-year sentence. In this game, Frankie’s best strategy is to confess, regardless of what Johnny does. When a player’s best strategy is the same regardless of the action of the other player, that strategy is said to be a dominant strategy. Frankie’s dominant strategy is to confess to the burglary.

For Johnny, the best strategy to follow, if Frankie confesses, is to confess. The best strategy to follow if Frankie does not confess is also to confess. Confessing is a dominant strategy for Johnny as well. A game in which there is a dominant strategy for each player is called a dominant strategy equilibrium. Here, the dominant strategy equilibrium is for both prisoners to confess; the payoff will be given by cell A in the payoff matrix.

From the point of view of the two prisoners together, a payoff in cell D would have been preferable. Had they both denied participation in the robbery, their combined sentence would have been four years in prison—two years each. Indeed, cell D offers the lowest combined prison time of any of the outcomes in the payoff matrix. But because the prisoners cannot communicate, each is likely to make a strategic choice that results in a more costly outcome. Of course, the outcome of the game depends on the way the payoff matrix is structured.

- 3834 reads