The prisoners’ dilemma was played once, by two players. The players were given a payoff matrix; each could make one choice, and the game ended after the first round of choices.

The real world of oligopoly has as many players as there are firms in the industry. They play round after round: a firm raises its price, another firm introduces a new product, the first firm cuts its price, a third firm introduces a new marketing strategy, and so on. An oligopoly game is a bit like a baseball game with an unlimited number of innings—one firm may come out ahead after one round, but another will emerge on top another day. In the computer industry game, the introduction of personal computers changed the rules. IBM, which had won the mainframe game quite handily, struggles to keep up in a world in which rivals continue to slash prices and improve quality.

Oligopoly games may have more than two players, so the games are more complex, but this does not change their basic structure. The fact that the games are repeated introduces new strategic considerations. A player must consider not just the ways in which its choices will affect its rivals now, but how its choices will affect them in the future as well.

We will keep the game simple, however, and consider a duopoly game. The two firms have colluded, either tacitly or overtly, to create a monopoly solution. As long as each player upholds the agreement, the two firms will earn the maximum economic profit possible in the enterprise.

There will, however, be a powerful incentive for each firm to cheat. The monopoly solution may generate the maximum economic profit possible for the two firms combined, but what if one firm captures some of the other firm’s profit? Suppose, for example, that two equipment rental firms, Quick Rent and Speedy Rent, operate in a community. Given the economies of scale in the business and the size of the community, it is not likely that another firm will enter. Each firm has about half the market, and they have agreed to charge the prices that would be chosen if the two combined as a single firm. Each earns economic profits of $20,000 per month.

Quick and Speedy could cheat on their arrangement in several ways. One of the firms could slash prices, introduce a new line of rental products, or launch an advertising blitz. This approach would not be likely to increase the total profitability of the two firms, but if one firm could take the other by surprise, it might profit at the expense of its rival, at least for a while.

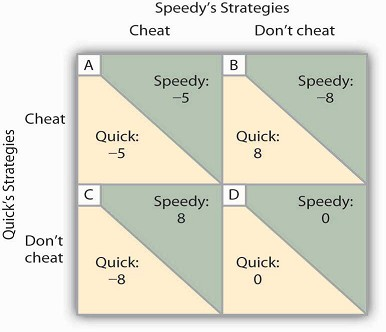

We will focus on the strategy of cutting prices, which we will call a strategy of cheating on the duopoly agreement. The alternative is not to cheat on the agreement. Cheating increases a firm’s profits if its rival does not respond. Figure 11.6 shows the payoff matrix facing the two firms at a particular time. As in the prisoners’ dilemma matrix, the four cells list the payoffs for the two firms. If neither firm cheats (cell D), profits remain unchanged.

Two rental firms, Quick Rent and Speedy Rent, operate in a duopoly market. They have colluded in the past, achieving a monopoly solution. Cutting prices means cheating on the arrangement; not cheating means maintaining current prices. The payoffs are changes in monthly profits, in thousands of dollars. If neither firm cheats, then neither firm’s profits will change. In this game, cheating is a dominant strategy equilibrium.

This game has a dominant strategy equilibrium. Quick’s preferred strategy, regardless of what Speedy does, is to cheat. Speedy’s best strategy, regardless of what Quick does, is to cheat. The result is that the two firms will select a strategy that lowers their combined profits!

Quick Rent and Speedy Rent face an unpleasant dilemma. They want to maximize profit, yet each is likely to choose a strategy inconsistent with that goal. If they continue the game as it now exists, each will continue to cut prices, eventually driving prices down to the point where price equals average total cost (presumably, the price-cutting will stop there). But that would leave the two firms with zero economic profits.

Both firms have an interest in maintaining the status quo of their collusive agreement. Overt collusion is one device through which the monopoly outcome may be maintained, but that is illegal. One way for the firms to encourage each other not to cheat is to use a tit-for-tat strategy. In a tit-for-tat strategy a firm responds to cheating by cheating, and it responds to cooperative behavior by cooperating. As each firm learns that its rival will respond to cheating by cheating, and to cooperation by cooperating, cheating on agreements becomes less and less likely.

Still another way firms may seek to force rivals to behave cooperatively rather than competitively is to use a trigger strategy, in which a firm makes clear that it is willing and able to respond to cheating by permanently revoking an agreement. A firm might, for example, make a credible threat to cut prices down to the level of average total cost—and leave them there—in response to any price-cutting by a rival. A trigger strategy is calculated to impose huge costs on any firm that cheats—and on the firm that threatens to invoke the trigger. A firm might threaten to invoke a trigger in hopes that the threat will forestall any cheating by its rivals.

Game theory has proved to be an enormously fruitful approach to the analysis of a wide range of problems. Corporations use it to map out strategies and to anticipate rivals’ responses. Governments use it in developing foreign-policy strategies. Military leaders play war games on computers using the basic ideas of game theory. Any situation in which rivals make strategic choices to which competitors will respond can be assessed using game theory analysis.

One rather chilly application of game theory analysis can be found in the period of the Cold War when the United States and the former Soviet Union maintained a nuclear weapons policy that was described by the acronym MAD, which stood for mutually assured destruction. Both countries had enough nuclear weapons to destroy the other several times over, and each threatened to launch sufficient nuclear weapons to destroy the other country if the other country launched a nuclear attack against it or any of its allies. On its face, the MAD doctrine seems, well, mad. It was, after all, a commitment by each nation to respond to any nuclear attack with a counterattack that many scientists expected would end human life on earth. As crazy as it seemed, however, it worked. For 40 years, the two nations did not go to war. While the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 ended the need for a MAD doctrine, during the time that the two countries were rivals, MAD was a very effective trigger indeed.

Of course, the ending of the Cold War has not produced the ending of a nuclear threat. Several nations now have nuclear weapons. The threat that Iran will introduce nuclear weapons, given its stated commitment to destroy the state of Israel, suggests that the possibility of nuclear war still haunts the world community.

KEY TAKEAWAYS

The key characteristics of oligopoly are a recognition that the actions of one firm will produce a response from rivals and that these responses will affect it. Each firm is uncertain what its rivals’ responses might be.

- The degree to which a few firms dominate an industry can be measured using a concentration ratio or a Herfindahl–Hirschman Index.

- One way to avoid the uncertainty firms face in oligopoly is through collusion. Collusion may be overt, as in the case of a cartel, or tacit, as in the case of price leadership.

- Game theory is a tool that can be used to understand strategic choices by firms.

- Firms can use tit-for-tat and trigger strategies to encourage cooperative behavior by rivals.

TRY IT!

Which model of oligopoly would seem to be most appropriate for analyzing firms’ behavior in each of the situations given below?

When South Airlines lowers its fare between Miami and New York City, North Airlines lowers its fare between the two cities. When South Airlines raises its fare, North Airlines does too.

Whenever Bank A raises interest rates on car loans, other banks in the area do too.

In 1986, Saudi Arabia intentionally flooded the market with oil in order to punish fellow OPEC members for cheating on their production quotas.

In July 1998, Saudi Arabia floated a proposal in which a group of eight or nine major oil-exporting countries (including OPEC members and some nonmembers, such as Mexico) would manage world

oil prices by adjusting their production.

Case in Point: Memory Chip Makers Caught in Global Price-Fixing Scheme

It may have been the remark by T.L. Chang, vice president of the Taiwan-based memory chip manufacturer Mosel-Vitelic that sparked the investigation by the U.S. Department of Justice Antitrust

Division. Mr. Chang was quoted in Taiwan’s Commercial Times in May 2002 as admitting to price-fixing meetings held in Asia among the major producers of DRAM, or dynamic random access memory.

DRAM is the most common semi-conductor main memory format for storage and retrieval of information that is used in personal computers, mobile phones, digital cameras, MP3 music players, and

other electronics products. At those meetings, as well as through emails and telephone conferences, the main manufacturers of DRAM decided not only what prices to charge and how much to make

available, but also exchanged information on DRAM sales for the purpose of monitoring and enforcing adherence to the agreed prices. The collusion lasted for three years—from 1999 to 2002. In

December 2001, DRAM prices were less than $1.00. By May of 2002, price had risen to the $4 to $5 range.

The companies that were directly injured by the higher chip prices included Dell, Compaq, Hewlett-Packard, Apple, IBM, and Gateway. In the end, though, the purchasers of their products paid

in the form of higher prices or less memory.

In December 2003, a Micron Technology sales manager pled guilty to obstruction of justice and served six months of home detention. The first chipmaker to plead guilty a year later was

Germany-based Infineon Technologies, which was fined $160 million. As of September 2007, five companies, Samsung being the largest, had been charged fines of more than $732 million, and over

3,000 days of jail time had been meted out to eighteen corporate executives.

The sharp reduction in the number of DRAM makers in the late 1990s undoubtedly made it easier to collude. The industry is still quite concentrated with Samsung holding 27.7% of the market and

Hynix 21.3%. The price, however, has fallen quite sharply in recent years.

Sources: Department of Justice, “Sixth Samsung Executive Agrees to Plead Guilty to Participating in DRAM Price-Fixing Cartel,” Press Release April 19, 2007; Stephen Labaton, “Infineon To

Pay a Fine in the Fixing of Chip Prices,” The New York Times, September 16, 2004; George Leopold and David Lammers, “DRAMs Under Gun in Antitrust Probe”, Electronic Engineering Times, 1124

(June 24, 2002):1, 102; Lee Sun-Young, “Samsung Cements DRAM Leadership,” Korea Herald, online, March 31, 2008.

ANSWERS TO TRY IT ! PROBLEMS

- North Airlines seems to be practicing a price strategy known in game theory as tit-for-tat.

- The banks could be engaged in tacit collusion, with Bank A as the price leader.

- Saudi Arabia appears to have used a trigger strategy, another aspect of game theory. In general, of course, participants hope they will never have to “pull” the trigger, because doing so harms all participants. After years of cheating by other OPEC members, Saudi Arabia did undertake a policy that hurt all members of OPEC, including itself; OPEC has never since regained the prominent role it played in oil markets.

- Saudi Arabia seems to be trying to create another oil cartel, a form of overt collusion.

- 3452 reads