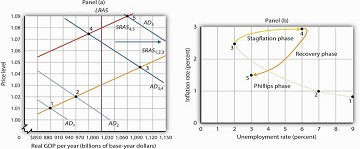

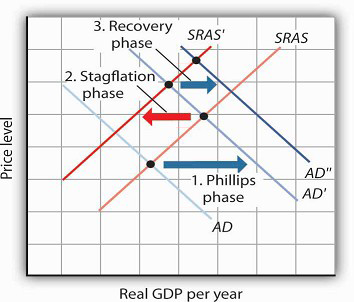

The stagflation phase shown in Figure 31.7 leaves the economy with a recessionary gap at point 4 in Panel (a). The economy is bumped into a recession by changing expectations. Policy makers can be expected to respond to the recessionary gap by boosting aggregate demand. That increase in aggregate demand will lead the economy into the recovery phase of the inflation–unemployment cycle.

Figure 31.8 illustrates a recovery phase. In Panel (a), aggregate demand increases to AD5, boosting the price level to 1.09 and real GDP to $1,060. The new price level represents a 1.4% ([1.09 − 1.075] / 1.075 = 1.4%) increase over the previous price level. The price level is higher, but the inflation rate has fallen sharply. Meanwhile, the increase in real GDP cuts the unemployment rate to 3.0%, shown by point 5 in Panel (b).

Policy makers act to increase aggregate demand in order to move the economy out of the recessionary gap created during the stagflation phase. Here, aggregate demand shifts to AD4, boosting the price level to 1.09 and real GDP to $1,060 billion at point 5 in Panel (a). The increase in real GDP reduces unemployment. The price level has risen, but at a slower rate than in the previous period. The result is a reduction in inflation. The new combination of unemployment and inflation is shown by point 5 in Panel (b).

Policies that stimulate aggregate demand and changes in expected price levels are not the only forces that affect the values of inflation and unemployment. Changes in production costs shift the short-run aggregate supply curve. Depending on when these changes occur, they can reinforce or reduce the swings in inflation and unemployment that mark the inflation–unemployment cycle. For example, Figure 31.4 shows that inflation was exceedingly low in the late 1990s. During this period, oil prices were very low—only $12.50 per barrel in 1998, for example. In terms of Figure 31.7, we can represent the low oil prices by a short-run aggregate supply curve that is to the right of SRAS4,5. That would mean that output would be somewhat higher, unemployment somewhat lower, and inflation somewhat lower than what is shown as point 5 in Panels (a) and (b) of Figure 31.8.

Comparing the late 1990s to the early 2000s, Figure 31.4 shows that both periods exhibit Phillips phases, but that the early 2000s has both higher inflation and higher unemployment. One way to explain these back-to-back Phillips phases is to look at Figure 31.6. Assume point 1 represents the economy in 2001, with aggregate demand increasing. At the same time, though, oil and other commodity prices were rising markedly—tripling between 2001 and 2007. Thus, the short-run aggregate supply curve was also shifting to the left of SRAS1,2,3. This would mean that output would be somewhat lower, unemployment somewhat higher, and inflation somewhat higher than what is shown as points 2 and 3 in Panels (a) and (b) of Figure 31.6. The 2000s Phillips curve would thus be above the late 1990s Phillips curve. While the Phillips phase of the early 2000s is farther from the origin than that of the late 1990s, it is noteworthy that the economy did not go through a severe stagflation phase, suggesting some learning about how to conduct monetary and fiscal policy.

So, while the economy does not move neatly through the phases outlined in the inflation– unemployment cycle, we can conclude that efforts to stimulate aggregate demand, together with changes in expectations, have played an important role in generating the inflation–unemployment patterns we observe in the past half-century.

Lags have played a crucial role in the cycle as well. If policy makers respond to a recessionary gap with an expansionary fiscal or monetary policy, then we know that aggregate demand will increase, but with a lag. Policy makers could thus undertake an expansionary policy and see little or no response at first. They might respond by making further expansionary efforts. When the first efforts finally shift aggregate demand, subsequent expansionary efforts can shift it too far, pushing real GDP beyond potential and creating an inflationary gap. These increases in aggregate demand create a Phillips phase. The economy’s correction of the gap creates a stagflation phase. If policy makers respond to the stagflation phase with a new round of expansionary policies, the initial result will be a recovery phase. Sufficiently large increases in aggregate demand can then push the economy into another Phillips phase, and the cycle continues. In early 2009, with the prospect of a large and long recession looming, there seems to be general agreement that expansionary monetary and fiscal policies are called for. At the same time, there is concern about lags leading to another round of stagflation.

KEY TAKEAWAYS

- In a Phillips phase, aggregate demand rises and boosts real GDP, lowering the unemployment rate. The price level rises by larger and larger percentages. Inflation thus rises while unemployment falls.

- A stagflation phase is marked by a leftward shift in short-run aggregate supply as wages and sticky prices are adjusted upwards. Unemployment rises while inflation remains high.

- In a recovery phase, policy makers boost aggregate demand. The price level rises, but at a slower rate than in the stagflation phase, so inflation falls. Unemployment falls as well.

TRY IT!

Using the model of aggregate demand and aggregate supply; sketch the changes in the curve(s) that produced each of the phases you identified in Try It! 16-1. Do not worry about specific numbers; just show the direction of changes in aggregate demand and/or short-run aggregate supply in each phase.

Case in Point: From the Challenging 1970s to the Calm 1990s

The path of U.S. inflation and unemployment followed a fairly consistent pattern of clockwise loops from 1961 to 2002, but the nature of these loops changed with changes in policy.

If we follow the cycle shown in Figure 31.4, we see that the three Phillips phases that began in 1961, 1972, and 1976 started at successively higher rates of inflation. Fiscal and

monetary policy became expansionary at the beginnings of each of these phases, despite rising rates of inflation.As inflation soared into the double-digit range in 1979, President Jimmy

Carter appointed a new Fed chairman, Paul Volcker. The president gave the new chairman a clear mandate: bring inflation under control, regardless of the cost. The Fed responded with a sharply

contractionary monetary policy and stuck with it even as the economy experienced its worse recession since the Great Depression.

Falling oil prices after 1982 contributed to an unusually long recovery phase: Inflation and unemployment both fell from 1982 to 1986. The inflation rate at which the economy started its next

Phillips phase was the lowest since the Phillips phase of the 1960s.

The Fed’s policies since then have clearly shown a reduced tolerance for inflation. The Fed shifted to a contractionary monetary policy in 1988, so that inflation during the 1986–1989

Phillips phase never exceeded 4%. When oil prices rose at the outset of the Persian Gulf War in 1990, the resultant swings in inflation and unemployment were much less pronounced than they

had been in the 1970s.

The Fed continued its effort to restrain inflation in 1994 and 1995. It shifted to a contractionary policy early in 1994 when the economy was still in a recessionary gap left over from the

1990–1991 recession. The Fed’s announced intention was to prevent any future increase in inflation. In effect, the Fed was taking explicit account of the lag in monetary policy. Had it

continued an expansionary monetary policy, it might well have put the economy in another Phillips phase. Instead, the Fed has conducted a carefully orchestrated series of slight shifts in

policy that succeeded in keeping the economy in the longest recovery phase since World War II.

To be sure, the stellar economic performance of the United States in the late 1990s was due in part to falling oil prices, which shifted the short-run aggregate supply curve to the right and

helped push inflation and unemployment down. But it seems clear that a good deal of the credit can be claimed by the Fed, which paid closer attention to the lags inherent in macroeconomic

policy. Ignoring those lags helped create the inflation– unemployment cycles that emerged with activist stabilization policies in the 1960s.

ANSWER TO TRY IT! PROBLEM

- 3227 reads