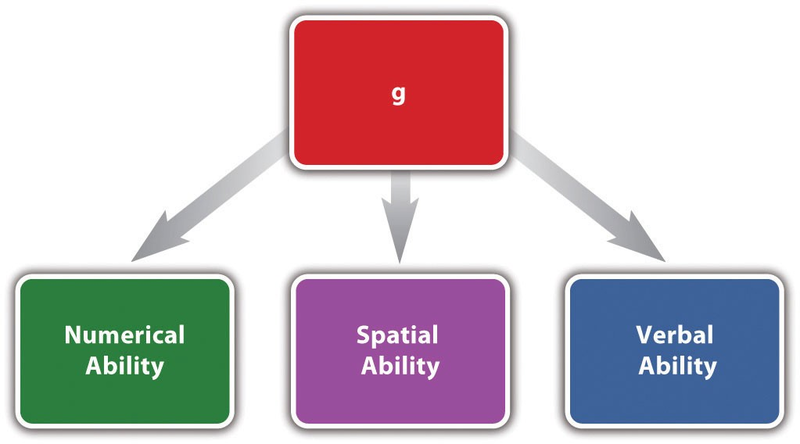

One important purpose of scientific theories is to organize phenomena in ways that help people think about them clearly and efficiently. The drive theory of social facilitation and social inhibition, for example, helps to organize and make sense of a large number of seemingly contradictory results. The multistore model of human memory efficiently summarizes many important phenomena: the limited capacity and short retention time of information that is attended to but not rehearsed, the importance of rehearsing information for long-term retention, the serial-position effect, and so on. Or consider a classic theory of intelligence represented by Figure 4.3 Representation of One Theory of Intelligence. According to this theory, intelligence consists of a general mental ability, g, plus a small number of more specific abilities that are influenced by g (Neisset et al., 1996). 1 Although there are other theories of intelligence, this one does a good job of summarizing a large number of statistical relationships between tests of various mental abilities. This includes the fact that tests of all basic mental abilities tend to be somewhat positively correlated and the fact that certain subsets of mental abilities (e.g., reading comprehension and analogy completion) are more positively correlated than others (e.g., reading comprehension and arithmetic).

Thus theories are good or useful to the extent that they organize more phenomena with greater clarity and efficiency. Scientists generally follow the principle of parsimony, which holds that a theory should include only as many concepts as are necessary to explain or interpret the phenomena of interest. Simpler, more parsimonious theories organize phenomena more efficiently than more complex, less parsimonious theories.

- 1959 reads