The most basic single-subject research design is the reversal design, also called the ABA design. During the first phase, A, a baseline is established for the dependent variable. This is the level of responding before any treatment is introduced, and therefore the baseline phase is a kind of control condition. When steady state responding is reached, phase B begins as the researcher introduces the treatment. There may be a period of adjustment to the treatment during which the behavior of interest becomes more variable and begins to increase or decrease. Again, the researcher waits until that dependent variable reaches a steady state so that it is clear whether and how much it has changed. Finally, the researcher removes the treatment and again waits until the dependent variable reaches a steady state. This basic reversal design can also be extended with the reintroduction of the treatment (ABAB), another return to baseline (ABABA), and so on.

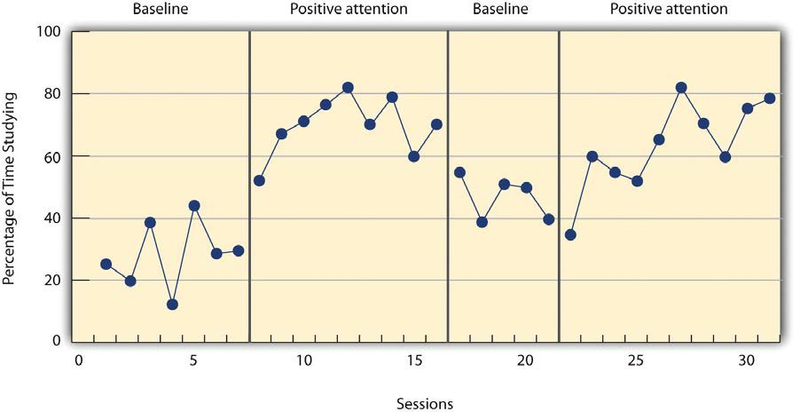

The study by Hall and his colleagues was an ABAB reversal design. Figure 10.3 approximates the data for Robbie. The percentage of time he spent studying (the dependent variable) was low during the first baseline phase, increased during the first treatment phase until it leveled off, decreased during the second baseline phase, and again increased during the second treatment phase.

Why is the reversal—the removal of the treatment—considered to be necessary in this type of design? Why use an ABA design, for example, rather than a simpler AB design? Notice that an AB design is essentially an interrupted time-series design applied to an individual participant. Recall that one problem with that design is that if the dependent variable changes after the treatment is introduced, it is not always clear that the treatment was responsible for the change. It is possible that something else changed at around the same time and that this extraneous variable is responsible for the change in the dependent variable. But if the dependent variable changes with the introduction of the treatment and then changes backwith the removal of the treatment, it is much clearer that the treatment (and removal of the treatment) is the cause. In other words, the reversal greatly increases the internal validity of the study.

There are close relatives of the basic reversal design that allow for the evaluation of more than one treatment. In a multiple-treatment reversal design, a baseline phase is followed by separate phases in which different treatments are introduced. For example, a researcher might establish a baseline of studying behavior for a disruptive student (A), then introduce a treatment involving positive attention from the teacher (B), and then switch to a treatment involving mild punishment for not studying (C). The participant could then be returned to a baseline phase before reintroducing each treatment—perhaps in the reverse order as a way of controlling for carryover effects. This particular multiple-treatment reversal design could also be referred to as an ABCACB design.

In an alternating treatments design, two or more treatments are alternated relatively quickly on a regular schedule. For example, positive attention for studying could be used one day and mild punishment for not studying the next, and so on. Or one treatment could be implemented in the morning and another in the afternoon. The alternating treatments design can be a quick and effective way of comparing treatments, but only when the treatments are fast acting.

- 5253 reads