The second way that extraneous variables can make it difficult to detect the effect of the independent variable is by becoming confounding variables. A confounding variable is an extraneous variable that differs on average acrosslevels of the independent variable. For example, in almost all experiments, participants’ intelligence quotients (IQs) will be an extraneous variable. But as long as there are participants with lower and higher IQs at each level of the independent variable so that the average IQ is roughly equal, then this variation is probably acceptable (and may even be desirable). What would be bad, however, would be for participants at one level of the independent variable to have substantially lower IQs on average and participants at another level to have substantially higher IQs on average. In this case, IQ would be a confounding variable.

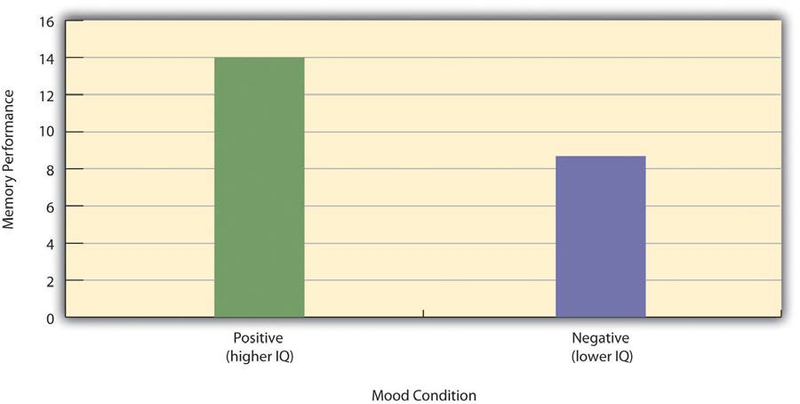

To confound means to confuse, and this is exactly what confounding variables do. Because they differ across conditions—just like the independent variable—they provide an alternative explanation for any observed difference in the dependent variable. Figure 6.1 shows the results of a hypothetical study, in which participants in a positive mood condition scored higher on a memory task than participants in a negative mood condition. But if IQ is a confounding variable—with participants in the positive mood condition having higher IQs on average than participants in the negative mood condition—then it is unclear whether it was the positive moods or the higher IQs that caused participants in the first condition to score higher. One way to avoid confounding variables is by holding extraneous variables constant. For example, one could prevent IQ from becoming a confounding variable by limiting participants only to those with IQs of exactly 100. But this approach is not always desirable for reasons we have already discussed. A second and much more general approach—random assignment to conditions—will be discussed in detail shortly.

KEY TAKEAWAYS

- An experiment is a type of empirical study that features the manipulation of an independent variable, the measurement of a dependent variable, and control of extraneous variables.

- Studies are high in internal validity to the extent that the way they are conducted supports the conclusion that the independent variable caused any observed differences in the dependent variable. Experiments are generally high in internal validity because of the manipulation of the independent variable and control of extraneous variables.

- Studies are high in external validity to the extent that the result can be generalized to people and situations beyond those actually studied. Although experiments can seem “artificial”—and low in external validity—it is important to consider whether the psychological processes under study are likely to operate in other people and situations.

EXERCISES

- Practice: List five variables that can be manipulated by the researcher in an experiment. List five variables that cannot be manipulated by the researcher in an experiment.

- Practice: For each of the following topics, decide whether that topic could be studied using an experimental research design and explain why or why not.

- Effect of parietal lobe damage on people’s ability to do basic arithmetic.

- Effect of being clinically depressed on the number of close friendships people have.

- Effect of group training on the social skills of teenagers with Asperger’s syndrome.

- Effect of paying people to take an IQ test on their performance on that test.

- 14852 reads