Many variables studied by psychologists are straightforward and simple to measure. These include sex, age, height, weight, and birth order. You can almost always tell whether someone is male or female just by looking. You can ask people how old they are and be reasonably sure that they know and will tell you. Although people might not know or want to tell you how much they weigh, you can have them step onto a bathroom scale. Other variables studied by psychologists—perhaps the majority—are not so straightforward or simple to measure. We cannot accurately assess people’s level of intelligence by looking at them, and we certainly cannot put their self-esteem on a bathroom scale. These kinds of variables are called constructs (pronounced CON-structs) and include personality traits (e.g., extroversion), emotional states (e.g., fear), attitudes (e.g., toward taxes), and abilities (e.g., athleticism).

Psychological constructs cannot be observed directly. One reason is that they often represent tendencies to think, feel, or act in certain ways. For example, to say that a particular college student is highly extroverted (see The Big Five) does not necessarily mean that she is behaving in an extroverted way right now. In fact, she might be sitting quietly by herself, reading a book. Instead, it means that she has a general tendency to behave in extroverted ways (talking, laughing, etc.) across a variety of situations. Another reason psychological constructs cannot be observed directly is that they often involve internal processes. Fear, for example, involves the activation of certain central and peripheral nervous system structures, along with certain kinds of thoughts, feelings, and behaviors—none of which is necessarily obvious to an outside observer. Notice also that neither extroversion nor fear “reduces to” any particular thought, feeling, act, or physiological structure or process. Instead, each is a kind of summary of a complex set of behaviors and internal processes.

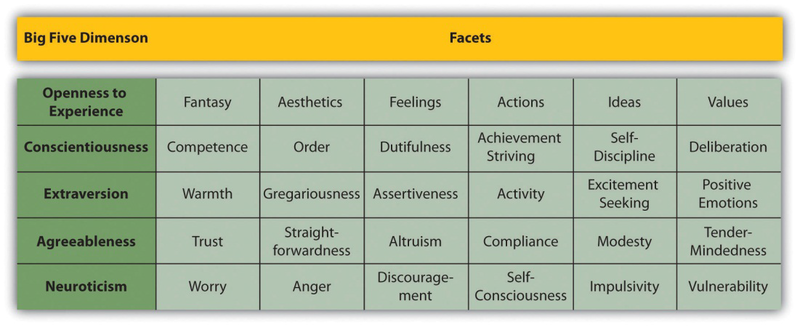

The Big Five

The Big Five is a set of five broad dimensions that capture much of the variation in human personality. Each of the Big Five can even be defined in terms of six more specific constructs called “facets” (Costa & McCrae, 1992). 1

The conceptual definition of a psychological construct describes the behaviors and internal processes that make up that construct, along with how it relates to other variables. For example, a conceptual definition of neuroticism (another one of the Big Five) would be that it is people’s tendency to experience negative emotions such as anxiety, anger, and sadness across a variety of situations. This definition might also include that it has a strong genetic component, remains fairly stable over time, and is positively correlated with the tendency to experience pain and other physical symptoms.

Students sometimes wonder why, when researchers want to understand a construct like self-esteem or neuroticism, they do not simply look it up in the dictionary. One reason is that many scientific constructs do not have counterparts in everyday language (e.g., working memory capacity). More important, researchers are in the business of developing definitions that are more detailed and precise—and that more accurately describe the way the world is—than the informal definitions in the dictionary. As we will see, they do this by proposing conceptual definitions, testing them empirically, and revising them as necessary. Sometimes they throw them out altogether. This is why the research literature often includes different conceptual definitions of the same construct. In some cases, an older conceptual definition has been replaced by a newer one that works better. In others, researchers are still in the process of deciding which of various conceptual definitions is the best.

- 10633 reads