Single-subject research is a type of quantitative research that involves studying in detail the behavior of each of a small number of participants. Note that the term single-subject does not mean that only one participant is studied; it is more typical for there to be somewhere between two and 10 participants. (This is why single-subject research designs are sometimes called small-n designs, where n is the statistical symbol for the sample size.) Single-subject research can be contrasted with group research, which typically involves studying large numbers of participants and examining their behavior primarily in terms of group means, standard deviations, and so on. The majority of this book is devoted to understanding group research, which is the most common approach in psychology. But single-subject research is an important alternative, and it is the primary approach in some areas of psychology.

Before continuing, it is important to distinguish single-subject research from two other approaches, both of which involve studying in detail a small number of participants. One is qualitative research, which focuses on understanding people’s subjective experience by collecting relatively unstructured data (e.g., detailed interviews) and analyzing those data using narrative rather than quantitative techniques. Single- subject research, in contrast, focuses on understanding objective behavior through experimental manipulation and control, collecting highly structured data, and analyzing those data quantitatively.

It is also important to distinguish single-subject research from case studies. A case studyis a detailed description of an individual, which can include both qualitative and quantitative analyses. (Case studies that include only qualitative analyses can be considered a type of qualitative research.) The history of psychology is filled with influential cases studies, such as Sigmund Freud’s description of “Anna O.”

(see The Case of “Anna O.”) and John Watson and Rosalie Rayner’s description of Little Albert (Watson & Rayner, 1920), 1 who learned to fear a white rat—along with other furry objects—when the researchers made a loud noise while he was playing with the rat. Case studies can be useful for suggesting new research questions and for illustrating general principles. They can also help researchers understand rare phenomena, such as the effects of damage to a specific part of the human brain. As a general rule, however, case studies cannot substitute for carefully designed group or single-subject research studies. One reason is that case studies usually do not allow researchers to determine whether specific events are causally related, or even related at all. For example, if a patient is described in a case study as having been sexually abused as a child and then as having developed an eating disorder as a teenager, there is no way to determine whether these two events had anything to do with each other. A second reason is that an individual case can always be unusual in some way and therefore be unrepresentative of people more generally. Thus case studies have serious problems with both internal and external validity.

The Case of “Anna O.”

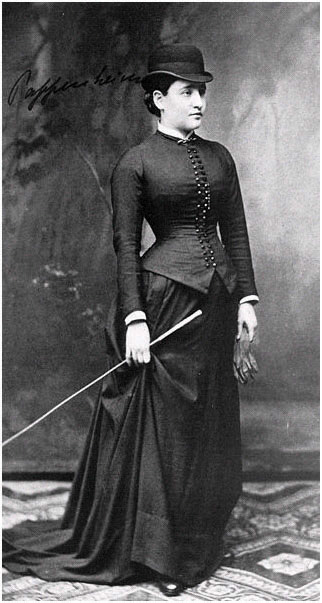

Sigmund Freud used the case of a young woman he called “Anna O.” to illustrate many principles of his theory of psychoanalysis (Freud, 1961). 2 (Her real name was Bertha Pappenheim, and she was an early feminist who went on to make important contributions to the field of social work.) Anna had come to Freud’s colleague Josef Breuer around 1880 with a variety of odd physical and psychological symptoms. One of them was that for several weeks she was unable to drink any fluids. According to Freud,

She would take up the glass of water that she longed for, but as soon as it touched her lips she would push it away like someone suffering from hydrophobia.…She lived only on fruit, such as melons, etc., so as to lessen her tormenting thirst (p. 9).

But according to Freud, a breakthrough came one day while Anna was under hypnosis.

[S]he grumbled about her English “lady-companion,” whom she did not care for, and went on to describe, with every sign of disgust, how she had once gone into this lady’s room and how her little dog—horrid creature!—had drunk out of a glass there. The patient had said nothing, as she had wanted to be polite.

After giving further energetic expression to the anger she had held back, she asked for something to drink, drank a large quantity of water without any difficulty, and awoke from her hypnosis with the glass at her lips; and thereupon the disturbance vanished, never to return.

Freud’s interpretation was that Anna had repressed the memory of this incident along with the emotion that it triggered and that this was what had caused her inability to drink. Furthermore, her recollection of the incident, along with her expression of the emotion she had repressed, caused the symptom to go away.

As an illustration of Freud’s theory, the case study of Anna O. is quite effective. As evidence for the theory, however, it is essentially worthless. The description provides no way of

knowing whether Anna had really repressed the memory of the dog drinking from the glass, whether this repression had caused her inability to drink, or whether recalling this “trauma” relieved

the symptom. It is also unclear from this case study how typical or atypical Anna’s experience was.

- 3389 reads