I do not know where the debate now resides regarding the adoption of Open Source Software (OSS), that is, if it is now a business or cultural issue. But I am sure that while it may have once been a debate within IT, it is not now. Much of the technical debate about functionality, quality, support, etc. now seems tired and even trivial. Are we still questioning the feasibility of community development and the viability of OSS? I guess so, I'm writing this, and you are reading it . . .

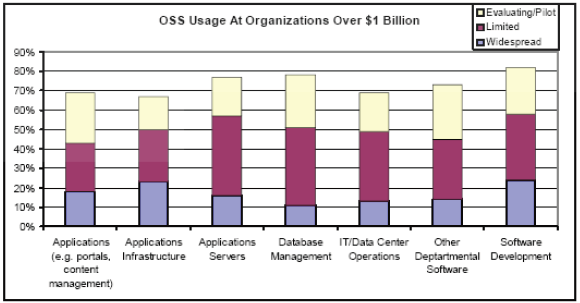

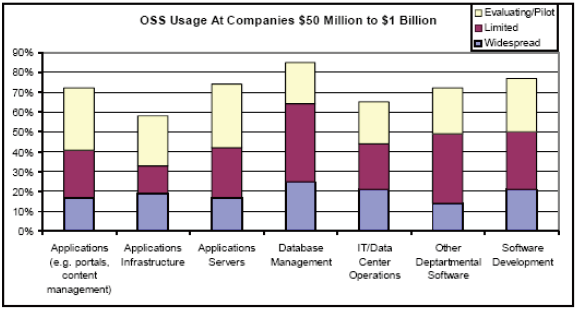

Based on Open Source's adoption among commercial software providers, OSS would appear to be an accepted and proven approach. According to a 2005 report by Optaros, The Growth of Open Source Software in Organizations 1 , “Some 87% of the 512 companies we surveyed are using open source software. Bigger companies are more likely to be open source users: all of the 156 companies with at least $50million in annual revenue were using open source.”

Many of academic computing's most prominent vendors not only rely on open source projects, but contribute to them as well, including: IBM (Eclipse, Sakai, SUSE Linux), Oracle (Berkeley's DB, Eclipse, Fusion Middleware, jDeveloper, Unbreakable Linux, PHP, Sakai) Novell (Apache, Eclipse, Jboss, Linux Kernel, Mozilla, MySQL, openLDAP, OpenOffice, openSUSE, Perl, PHP, PostgreSQL, Samba, Tomcat, Xen) SUN Microsystems (GNU/Linux, Java, OpenOccice, OpenSolaris, Sakai, uPortal), Sungard Higher Education (Sakai, uPortal) and Unicon (Sakai, uPortal, Zimbra). There are some very telling examples of companies who have integrated Open Source into their businesses; those who simply support open source tools (too many to name), those who have released a previously proprietary code base into the public domain (e.g. SUN Microsystems' Java programming language), and most telling of the acceptance of open source and community development within technology markets, those who have actually integrated open source t ools into their commercial product lines (e.g. SunGard's use of uPortal within Luminis III) - hardly the move to make if you consider open source products to be poor in quality or unreliable in development.

And yet there is another area, often overlooked, where OSS has proved valuable to commercial developers. In addition to the actual software, the movement has also helped redefine the software development life cycle, that is, how applications are designed, developed and deployed. “Community Development” has become a standard practice capitalizing on Linus' Law described by Eric Raymond in The Cathedral and The Bazaar 2 as, “given enough eyeballs, all bugs are shallow.” Many of the techniques associated with “extreme programming” and “agile development,” that are common today in software development, coevolved with open source and free software projects as they adopted Bazaar-style open development models: pair-programming, user-developers, short development cycles, iteration, etc. Many of today's commercial providers producing proprietary software have adopted “open” development methods. David Treadwell, corporate vice president of the .Net Developer Platform group at Microsoft, said in a November 2005 interview with eWeek 3 that Microsoft encourages agile methodologies such as Scrum and extreme programming, “the concept where you might have two people working on a given piece of code and the idea is that two minds are better than one. Because you can find problems faster.” In another example, Common Services Architecture 4 “represents a new paradigm for collaborative software development within SunGard. It's a collaborative development process” a way of creating software that allows SunGard product development teams around the world to share, contribute to, and leverage, each other's work.”

So there seems to be a clear indication from those outside academic computing - in fact those that we within academic computing are paying for services - that the technical debate regarding open source is over. However, the decision-makers in academics, do not seem as willing to accept the same, and appear to be taking up the debate all over again, albeit with different arguments.

- 1651 reads