The brief introduction to OM wants to introduce the important role of packaging in all activities of a company. This section will describe a model of OM discipline that the authors have taken as a reference for dealing with the packaging topic.

According to Drejer et al1, the “Scientific Management” approach to industrial engineering developed by Frederick Taylor in the 1910s is widely regarded as the basis on which OM, as a discipline, is founded. This approach involved reducing a system to its simplest elements, analysing them, and calculating how to improve each element.

OM is the management function applied to manufacturing, service industries and no-profit organizations2 and is responsible for all activities directly concerned with making a product, collecting various inputs and converting them into desired outputs through operations3. Thus, OM includes inputs, outputs, and operations. Examples of inputs might be raw materials, money, people, machines, and time. Outputs are goods, services, staff wages, and waste materials. Operations include activities such as manufacturing, assembly, packing, serving, and training4. The operations can be of two categories: those that add value and those with no added value. The first category includes the product processing steps (e.g. operations that transform raw materials into good products). The second category is actually a kind of waste. Waste consists of all unnecessary movements for completing an operation, which should therefore be eliminated. Examples of this are waiting time, piling products, re-loading, and movements. Moreover, it is important to underline, right from the start, that the packaging system can represent a source of waste, but at the same time, a possible source of opportunities. Before waste-to-energy solutions, for example, it is possible to consider the use of recycled packages for shipping products. The same package may be used more than once; for example, if a product is sent back by the consumer, the product package could be used for the next shipment.

OM can be viewed as the tool behind the technical improvements that make production efficient5. It may include three performance aims: efficiency, effectiveness, and customer satisfaction. Whether the organization is in the private or the public sector, a manufacturing or non-manufacturing organization, a profit or a non-profit organization, the optimal utilization of resources is always a desired objective. According to Waters6, OM can improve efficiency of an operation system to do things right and as a broader concept. Effectiveness involves optimality in the fulfilment of multiple objectives with possible prioritization within them; it refers to doing the seven right things well: the right operation, right quantity, right quality, right supplier, right time, right place and right price. The OM system has to be not only profitable and/or efficient, but must necessarily satisfy customers.

According to Kleinforfer et al.7, the tools and elements of the management system need to be integrated with company strategy. The locus of the control and methodology of these tools and management systems is directly associated with operations. With the growing realization of the impact of these innovations on customers and profit, operations began their transformation from a “neglected stepsister needed to support marketing and finance to a cherished handmaiden of value creation”8.

According to Hammer9, a wave of change began in the 1980s called Business Process Reengineering -10(BRP). BPR provided benefits to non-manufacturing processes by applying the efforts that Total Quality Management -11(TQM) and Just In Time -12(JIT) had applied to manufacturing. Gradually, this whole evolution came to be known as Process Management, a name that emphasized the crucial importance of processes in value creation and management. Process management is given further impetus by the core competency movement13, which stressed the need for companies to develop technology-based and organizational competencies that their competitors could not easily imitate. The confluence of the core competency and process management movements led to many of the past decade’s changes including the unbundling of value chains, outsourcing, and innovations in contracting and supply chains. People now recognize the importance of aligning strategy and operations, a notion championed by Skinner14.

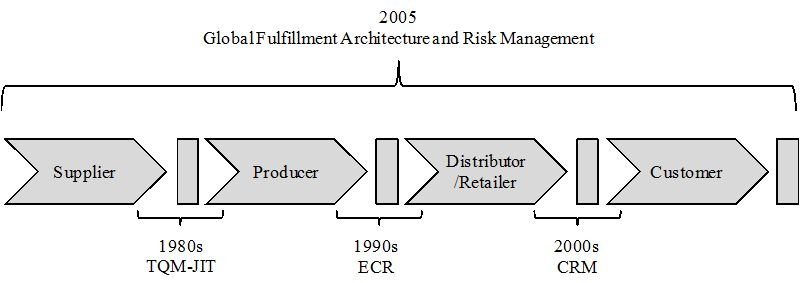

As companies developed their core competencies and included them in their business processes, the tools and concepts of TQM and JIT have been applied to the development of new products and supply chain management15. Generally, companies first incorporated JIT between suppliers and production units. The 1980s’ introduction of TQM and JIT in manufacturing gave rise to the recognition that the principles of excellence applied to manufacturing operations could also improve business processes and that organizations structured according to process management principles would improve. According to Kleindorfer et al.16, the combination of these process management fundamentals, information and communication technologies, and globalization has provided the foundations and tools for managing today’s outsourcing, contract manufacturing, and global supply chains. In the 1990s companies moved over to optimized logistics (including Efficient Consumer Response17 - (ECR)) between producers and distributors, then to Customer Relationship Management18 - (CRM) and finally to global fulfilment architecture and risk management. These supply chain-focused trends inspired similar trends at the corporate level as companies moved from lean operations to lean enterprises and now to lean consumption19. Figure 8.1 shows these trends and drivers, based on Kleindorfer et al.20.

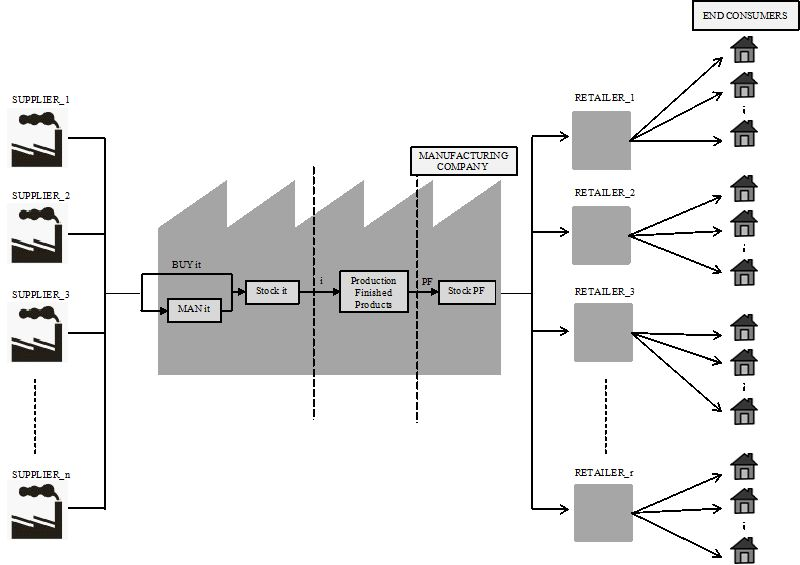

In order to manage the supply chain, organizations have to make different decisions about OM that can be classified as strategic, tactical, and operational. A graphical representation of the three decision levels of OM is shown in Figure 8.221.

The three decisions’ levels of OM interact and depend on each other: the strategic level is a prerequisite for the tactical level, and this in turn is a prerequisite for the operational level.

Strategic, tactical, and operational levels of OM are closely connected with the packaging system. Packaging is cross-functional to all company operations, since it is handled in several parts of the supply chain (e.g. marketing, production, logistics, purchasing, etc.). A product packaging system plays a fundamental role in the successful design and management of the operations in the supply chain. An integrated management of the packaging system from the strategic (e.g. decision of defining a new packaging solution), tactical (e.g. definition of the main packaging requirements) and operational (e.g. development of the physical packaging system and respect of the requirements) point of view, allows companies to find the optimal management of the packaging system and to reduce packaging cost.

A general framework of product packaging and the packaging logistics system will be presented in Section 3.

- 2557 reads