One of the most important factors influencing the physical and mental condition of an employee – and, thus, his or her ability to cope with work – is the degree to which employees are able to recover from fatigue and stress at work. Recovery can be defined as the period of time that an individual needs to return to prestressor level of functioning following the termination of a stressor1. Jansen argued that fatigue should not be regarded as a discrete disorder but as a continuum ranging from mild, frequent complaints seen in the community to the severe, disabling fatigue characteristics of burnout, overstrain, or chronic fatigue syndrome2. It is necessary that recovery is properly positioned within this continuum not only in the form of lunch breaks, rest days, weekends or summer holidays, but even in the simple form of breaks or micro-pauses in work shifts.

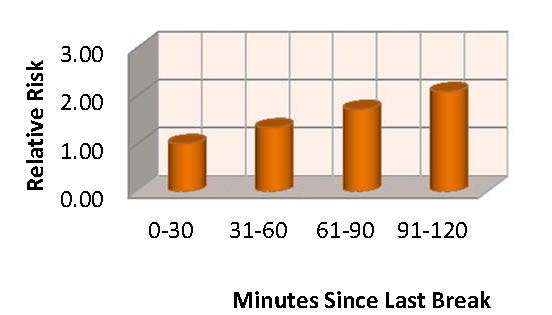

Work breaks are generally defined as “planned or spontaneous suspension from work on a task that interrupts the flow of activity and continuity” 3. Breaks can potentially be disruptive to the flow of work and the completion of a task. The potential negative consequences of breaks for the person being interrupted include loss of available time to complete a task, a temporary disengagement from the task, procrastination (i.e. excessive delays in starting or continuing work on a task), and the reduction in productivity; the break can lead to a loss of time to complete activities. However, breaks can serve multiple positive functions for the person being interrupted, such as stimulation for the individual performing a job that is routine or boring, opportunities to engage in activities that are essential to emotional wellbeing, job satisfaction, sustained productivity, and time for the subconscious to process complex problems that require creativity4. In addition, regular breaks seem to be an effective way to control the accumulation of risk during the industrial shift. The few studies on work breaks indicate that people need occasional changes... the shift or an oscillation between work and recreation, mainly when fatigued or working continuously for an extended period5. A series of laboratory studies in the workplace have been conducted to evaluate the effects of breaks in more recent times; however, there appears to be a single recent study that examined in depth the impact of rest breaks, focusing on the risk of injury. Tucker’s study6, 7 focused attention on the risk of accidents in the workplace, noting that the inclusion of work breaks can reduce this risk. Tucker examined accidents in a car assembly plant, where workers were given a 15-minute break after each 2-hour period of continuous work. The number of accidents within each of four periods of 30 minutes between successive interruptions was calculated, and the risk in each period of 30 minutes was expressed in the first period of 30 minutes immediately after the break. The results are shown in Figure 5.5, and it is clear that the accident risk increased significantly, and less linearly, between the successive breaks. The results showed that rest breaks neutralise successfully accumulation of risk over 2 hours of continuous work. The risk immediately after a pause has been reduced to a rate close to that recorded at the start of the previous work period. However, the effects of the breaks are short-term recovery.

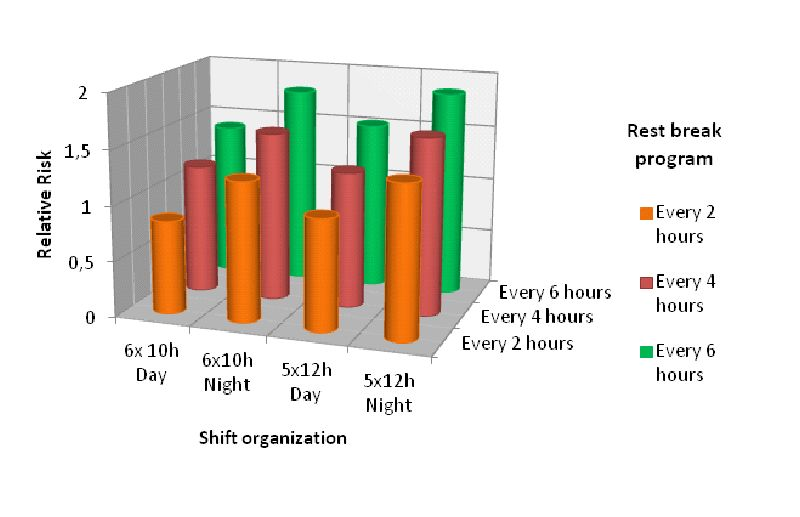

A 2006 study by Folkard and Lombardi showed the impact of frequent pauses of different shift systems8. The results of these studies confirm that breaks, even for a short period of time, are positively reflected from physical and psychic viewpoints on the operator’s work (see Figure 9.12).

Proper design of work–rest schedule that involves frequency, duration, and timing of rest breaks may be effective in improving workers’ comfort, health, and productivity. But today, work breaks are not taken into proper consideration, and there are ongoing efforts to create systems that better manage the business in various areas, especially in manufacturing. From the analysis of the literature, in fact, there has been the almost total lack of systems for the management of work breaks in an automatic manner. The only exception is the software that stimulates workers at VDT to take frequent breaks and recommend performing exercises during breaks. The validity and effectiveness of this type of software has been demonstrated by several studies, including one by Van Den Heuvel9that evaluated the effects of work-related disorders of the neck and upper limbs and the productivity of computer workers stimulated to take regular breaks and perform physical exercises with the use of an adapted version of WorkPace, Niche Software Ltd., New, and that of McLean (2001)10 that examined the benefits of micro-breaks to prevent onset or progression of cumulative trauma disorders for the computerised environment, mediated using the program Ergobreak 2.2.

In future, therefore, researchers should focus their efforts on the introduction of management systems of breaks and countering the rates of increase in the risk of accidents during long periods of continuous work to improve productivity.

- 2195 reads