Can divergence occur if no physical barriers are in place to separate individuals who continue to live and reproduce in the same habitat? A number of mechanisms for sympatric speciation have been proposed and studied.

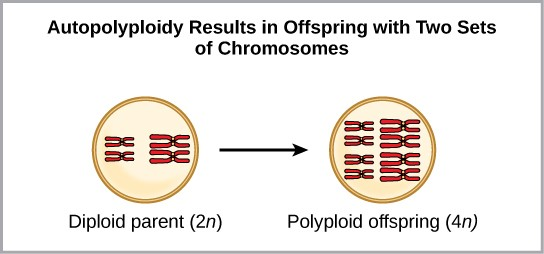

One form of sympatric speciation can begin with a chromosomal error during meiosis or the formation of a hybrid individual with too many chromosomes. Polyploidy is a condition in which a cell, or organism, has an extra set, or sets, of chromosomes. Scientists have identified two main types of polyploidy that can lead to reproductive isolation of an individual in the polyploid state. In some cases a polyploid individual will have two or more complete sets of chromosomes from its own species in a condition called autopolyploidy (Figure 11.17). The prefix “auto” means self, so the term means multiple chromosomes from one’s own species. Polyploidy results from an error in meiosis in which all of the chromosomes move into one cell instead of separating.

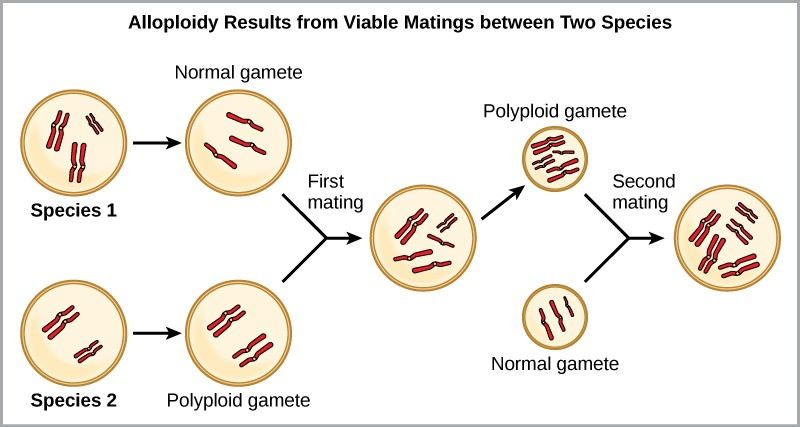

For example, if a plant species with 2n= 6 produces autopolyploid gametes that are also diploid (2n=6, when they should be n= 3), the gametes now have twice as many chromosomes as they should have. These new gametes will be incompatible with the normal gametes produced by this plant species. But they could either self-pollinate or reproduce with other autopolyploid plants with gametes having the same diploid number. In this way, sympatric speciation can occur quickly by forming offspring with 4n called a tetraploid. These individuals would immediately be able to reproduce only with those of this new kind and not those of the ancestral species. The other form of polyploidy occurs when individuals of two different species reproduce to form a viable offspring called an allopolyploid. The prefix “allo” means “other” (recall from allopatric); therefore, an allopolyploid occurs when gametes from two different species combine. Figure 11.18 illustrates one possible way an allopolyploidy can form. Notice how it takes two generations, or two reproductive acts, before the viable fertile hybrid results.

The cultivated forms of wheat, cotton, and tobacco plants are all allopolyploids. Although polyploidy occurs occasionally in animals, most chromosomal abnormalities in animals are lethal; it takes place most commonly in plants. Scientists have discovered more than 1/2 of all plant species studied relate back to a species evolved through polyploidy.

Sympatric speciation may also take place in ways other than polyploidy. For example, imagine a species of fish that lived in a lake. As the population grew, competition for food also grew. Under pressure to find food, suppose that a group of these fish had the genetic flexibility to discover and feed off another resource that was unused by the other fish. What if this new food source was found at a different depth of the lake? Over time, those feeding on the second food source would interact more with each other than the other fish; therefore they would breed together as well. Offspring of these fish would likely behave as their parents and feed and live in the same area, keeping them separate from the original population. If this group of fish continued to remain separate from the first population, eventually sympatric speciation might occur as more genetic differences accumulated between them.

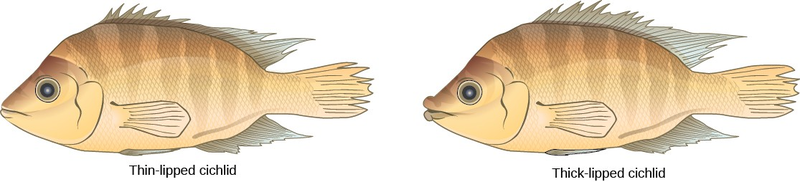

This scenario does play out in nature, as do others that lead to reproductive isolation. One such place is Lake Victoria in Africa, famous for its sympatric speciation of cichlid fish. Researchers have found hundreds of sympatric speciation events in these fish, which have not only happened in great number, but also over a short period of time. Figure 11.19 shows this type of speciation among a cichlid fish population in Nicaragua. In this locale, two types of cichlids live in the same geographic location; however, they have come to have different morphologies that allow them to eat various food sources.

Finally, a well-documented example of ongoing sympatric speciation occurred in the apple maggot fly, Rhagoletis pomonella,which arose as an isolated population sometime after the introduction of the apple into North America. The native population of flies fed on hawthorn species and is host-specific: it only infests hawthorn trees. Importantly, it also uses the trees as a location to meet for mating. It is hypothesized that either through mutation or a behavioral mistake, flies jumped hosts and met and mated in apple trees, subsequently laying their eggs in apple fruit. The offspring matured and kept their preference for the apple trees effectively dividing the original population into two new populations separated by host species, not by geography. The host jump took place in the nineteenth century, but there are now measureable differences between the two populations of fly. It seems likely that host specificity of parasites in general is a common cause of sympatric speciation.

- 4064 reads