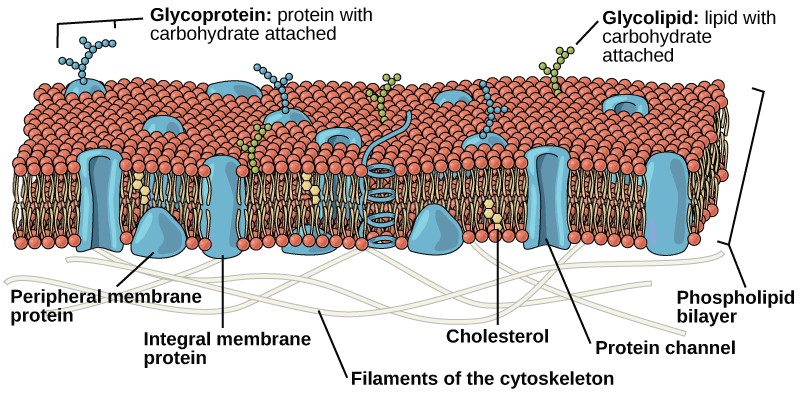

In 1972, S. J. Singer and Garth L. Nicolson proposed a new model of the plasma membrane that, compared to earlier understanding, better explained both microscopic observations and the function of the plasma membrane. This was called the fluid mosaic model. The model has evolved somewhat over time, but still best accounts for the structure and functions of the plasma membrane as we now understand them. The fluid mosaic model describes the structure of the plasma membrane as a mosaic of components—including phospholipids, cholesterol, proteins, and carbohydrates—in which the components are able to flow and change position, while maintaining the basic integrity of the membrane. Both phospholipid molecules and embedded proteins are able to diffuse rapidly and laterally in the membrane. The fluidity of the plasma membrane is necessary for the activities of certain enzymes and transport molecules within the membrane. Plasma membranes range from 5–10 nm thick. As a comparison, human red blood cells, visible via light microscopy, are approximately 8 µm thick, or approximately 1,000 times thicker than a plasma membrane. (Figure 3.18 )

The plasma membrane is made up primarily of a bilayer of phospholipids with embedded proteins, carbohydrates, glycolipids, and glycoproteins, and, in animal cells, cholesterol. The amount of cholesterol in animal plasma membranes regulates the fluidity of the membrane and changes based on the temperature of the cell’s environment. In other words, cholesterol acts as antifreeze in the cell membrane and is more abundant in animals that live in cold climates.

The main fabric of the membrane is composed of two layers of phospholipid molecules, and the polar ends of these molecules (which look like a collection of balls in an artist’s rendition of the model) (Figure 3.18) are in contact with aqueous fluid both inside and outside the cell. Thus, both surfaces of the plasma membrane are hydrophilic. In contrast, the interior of the membrane, between its two surfaces, is a hydrophobic or nonpolar region because of the fatty acid tails. This region has no attraction for water or other polar molecules.

Proteins make up the second major chemical component of plasma membranes. Integral proteins are embedded in the plasma membrane and may span all or part of the membrane. Integral proteins may serve as channels or pumps to move materials into or out of the cell. Peripheral proteins are found on the exterior or interior surfaces of membranes, attached either to integral proteins or to phospholipid molecules. Both integral and peripheral proteins may serve as enzymes, as structural attachments for the fibers of the cytoskeleton, or as part of the cell’s recognition sites.

Carbohydrates are the third major component of plasma membranes. They are always found on the exterior surface of cells and are bound either to proteins (forming glycoproteins) or to lipids (forming glycolipids). These carbohydrate chains may consist of 2–60 monosaccharide units and may be either straight or branched. Along with peripheral proteins, carbohydrates form specialized sites on the cell surface that allow cells to recognize each other.

Evolution In Action

How Viruses Infect Specific Organs

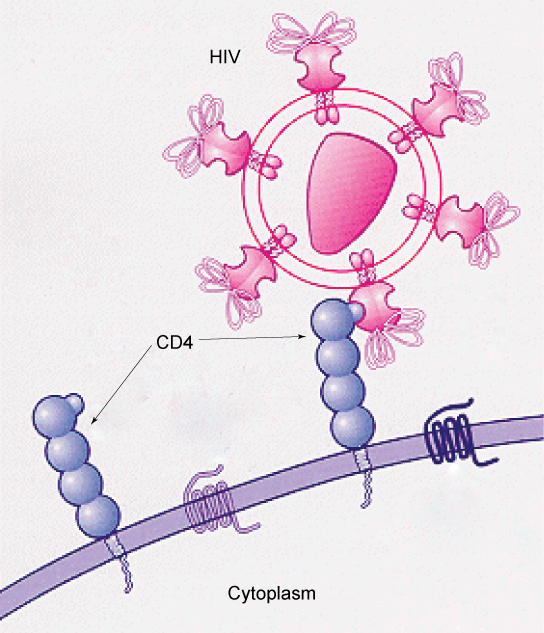

Specific glycoprotein molecules exposed on the surface of the cell membranes of host cells are exploited by many viruses to infect specific organs. For example, HIV is able to penetrate the plasma membranes of specific kinds of white blood cells called T-helper cells and monocytes, as well as some cells of the central nervous system. The hepatitis virus attacks only liver cells.

These viruses are able to invade these cells, because the cells have binding sites on their surfaces that the viruses have exploited with equally specific glycoproteins in their coats.

(Figure 3.19). The cell is tricked by the mimicry of the virus

coat molecules, and the virus is able to enter the cell. Other recognition sites on the virus’s surface interact with the human immune system, prompting the body to produce antibodies.

Antibodies are made in response to the antigens (or proteins associated with invasive pathogens). These same sites serve as places for antibodies to attach, and either destroy or inhibit the

activity of the virus. Unfortunately, these sites on HIV are encoded by genes that change quickly, making the production of an effective vaccine against the virus very difficult. The virus

population within an infected individual quickly evolves through mutation into different populations, or variants, distinguished by differences in these recognition sites. This rapid change

of viral surface markers decreases the effectiveness of the person’s immune system in attacking the virus, because the antibodies will not recognize the new variations of the surface

patterns.

- 11387 reads