To understand how gene expression is regulated, we must first understand how a gene becomes a functional protein in a cell. The process occurs in both prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells, just in slightly different fashions.

Because prokaryotic organisms lack a cell nucleus, the processes of transcription and translation occur almost simultaneously. When the protein is no longer needed, transcription stops. As a result, the primary method to control what type and how much protein is expressed in a prokaryotic cell is through the regulation of DNA transcription into RNA. All the subsequent steps happen automatically. When more protein is required, more transcription occurs. Therefore, in prokaryotic cells, the control of gene expression is almost entirely at the transcriptional level.

The first example of such control was discovered using E. coliin the 1950s and 1960s by French researchers and is called the lacoperon. The lacoperon is a stretch of DNA with three adjacent genes that code for proteins that participate in the absorption and metabolism of lactose, a food source for E. coli. When lactose is not present in the bacterium’s environment, the lacgenes are transcribed in small amounts. When lactose is present, the genes are transcribed and the bacterium is able to use the lactose as a food source. The operon also contains a promoter sequence to which the RNA polymerase binds to begin transcription; between the promoter and the three genes is a region called the operator. When there is no lactose present, a protein known as a repressor binds to the operator and prevents RNA polymerase from binding to the promoter, except in rare cases. Thus very little of the protein products of the three genes is made. When lactose is present, an end product of lactose metabolism binds to the repressor protein and prevents it from binding to the operator. This allows RNA polymerase to bind to the promoter and freely transcribe the three genes, allowing the organism to metabolize the lactose.

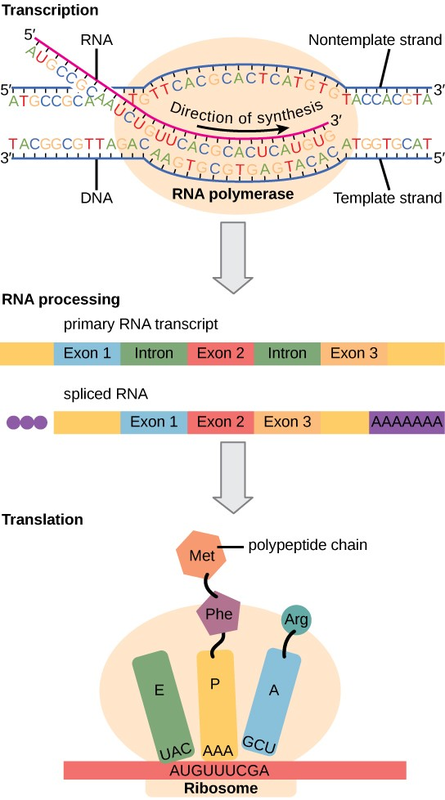

Eukaryotic cells, in contrast, have intracellular organelles and are much more complex. Recall that in eukaryotic cells, the DNA is contained inside the cell’s nucleus and it is transcribed into mRNA there. The newly synthesized mRNA is then transported out of the nucleus into the cytoplasm, where ribosomes translate the mRNA into protein. The processes of transcription and translation are physically separated by the nuclear membrane; transcription occurs only within the nucleus, and translation only occurs outside the nucleus in the cytoplasm. The regulation of gene expression can occur at all stages of the process (Figure 9.22). Regulation may occur when the DNA is uncoiled and loosened from nucleosomes to bind transcription factors (epigenetic level), when the RNA is transcribed (transcriptional level), when RNA is processed and exported to the cytoplasm after it is transcribed (post-transcriptional level), when the RNA is translated into protein (translational level), or after the protein has been made ( post-translational level).

The differences in the regulation of gene expression between prokaryotes and eukaryotes are summarized in Table 9.2.

|

Prokaryotic organisms |

Eukaryotic organisms |

|

Lack nucleus |

Contain nucleus |

|

RNA transcription and protein translation occur almost simultaneously |

RNA transcription occurs prior to protein translation, and it takes place in the nucleus. RNA translation to protein occurs in the cytoplasm. RNA post-processing includes addition of a 5' cap, poly-A tail, and excision of introns and splicing of exons. |

|

Gene expression is regulated primarily at the transcriptional level |

Gene expression is regulated at many levels (epigenetic, transcriptional, post-transcriptional, translational, and posttranslational) |

Evolution In Action

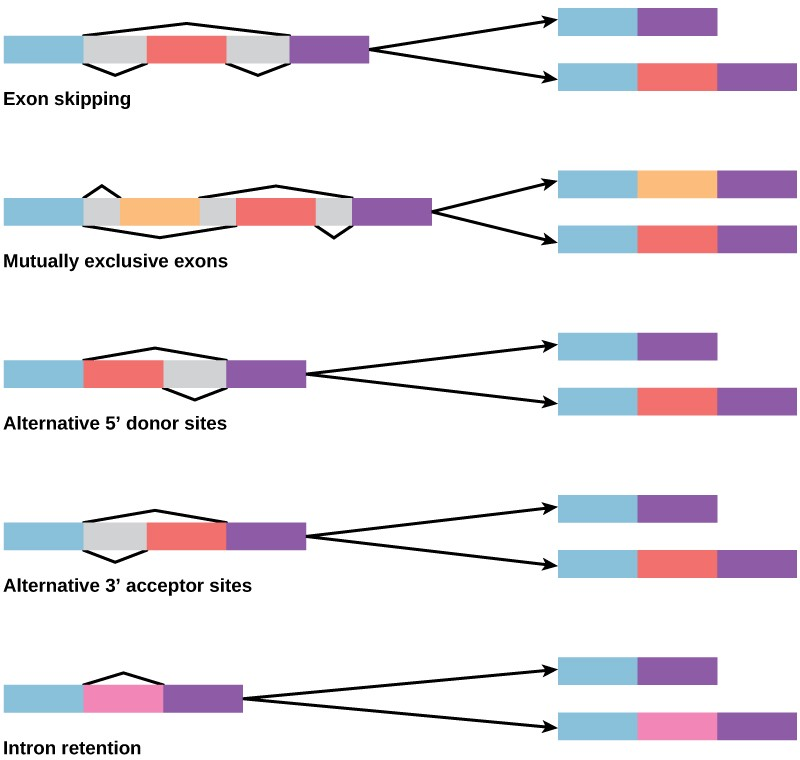

Alternative RNA Splicing

In the 1970s, genes were first observed that exhibited alternative RNA splicing. Alternative RNA splicing is a mechanism that allows different protein products to be produced from one gene when different combinations of introns (and sometimes exons) are removed from the transcript (Figure 9.23). This alternative splicing can be haphazard, but more often it is controlled and acts as a mechanism of gene regulation, with the frequency of different splicing alternatives controlled by the cell as a way to control the production of different protein products in different cells, or at different stages of development. Alternative splicing is now understood to be a common mechanism of gene regulation in eukaryotes; according to one estimate, 70% of genes in humans are expressed as multiple proteins through alternative splicing.

How could alternative splicing evolve? Introns have a beginning and ending recognition sequence, and it is easy to imagine the failure of the splicing mechanism to identify the end of an intron and find the end of the next intron, thus removing two introns and the intervening exon. In fact, there are mechanisms in place to prevent such exon skipping, but mutations are likely to lead to their failure. Such “mistakes” would more than likely produce a nonfunctional protein. Indeed, the cause of many genetic diseases is alternative splicing rather than mutations in a sequence. However, alternative splicing would create a protein variant without the loss of the original protein, opening up possibilities for adaptation of the new variant to new functions. Gene duplication has played an important role in the evolution of new functions in a similar way—by providing genes that may evolve without eliminating the original functional protein.

- 11695 reads