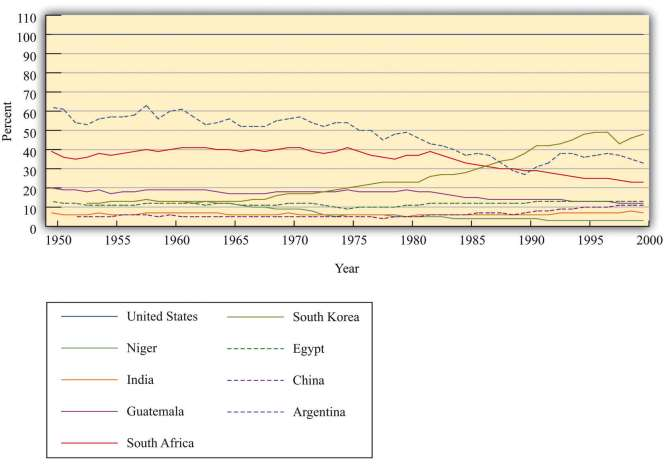

So far so good. But ***Figure 6.10 "Some Evidence of Divergence" shows the growth experience over the same period for a more diverse group of countries. This group is largely composed of poorer countries. The picture here is very different: we do not see convergence. There is no evidence that the poorer countries are growing faster than the richer countries. In some cases, there even appears to be divergence: poor countries growing more slowly than rich countries so that output levels in rich and poor countries move further apart.

Table 6.5 "Evidence from Select Countries" shows more data for some of these countries. It lists the level of initial GDP per person and the average growth rate in GDP per person between the early 1950s and the end of the century. For example, Argentina had real GDP per person of $6,430 in 1950 (in year 1996 dollars) and grew at an average rate of 1.25 percent over the 50-year period. Egypt and South Korea had very close levels of GDP per person in the early 1950s, but growth in South Korea was much higher than that in Egypt: by the year 2000, GDP per person was $15,876 in South Korea but only $4,184 in Egypt. These two countries very clearly diverged rather than converged. Looking at China, the level of GDP per person in the early 1950s was less than 10 percent that of Argentina. By 2000, GDP per person in China was about 33 percent of that in Argentina.

Table 6.5 Evidence from Select Countries

|

Country (Starting Year) |

Real GDP per Capita (Year 1996 US Dollars) |

Percentage Average Growth Rate to 2000 |

|

Argentina (1950) |

6,430 |

1.25 |

|

Egypt (1950) |

1,371 |

2.33 |

|

China (1952) |

584 |

4.0 |

|

South Korea (1953) |

1,328 |

5.5 |

Source: Penn World Tables

Overall, this evidence suggests that our theory can explain the behavior over time of some but not all countries. If we look at relatively rich countries, then we do see evidence of convergence. Across broader groups of countries, we do not see convergence, and we see some evidence of divergence.

- 瀏覽次數:1227