If Juan does not trade with the rest of the world, his only way to save for the future is by building up his capital stock. In this case, national savings equal investment. An economy that does not trade with other countries is called a closed economy. An economy that trades with other countries is called an open economy. In the modern world, no economy is completely closed, although some economies (such as Belgium) are much more open than others (such as North Korea). The world as a whole is a closed economy, of course.

If Solovenia is an open economy, Juan has other options. He might decide that he can get a better return on his savings by investing in foreign assets (such as Italian real estate, shares of Australian firms, or Korean government bonds). Domestic investment would then be less than national savings. Juan is lending to the rest of the world.

Alternatively, Juan might think that the benefits of investment in his home economy are sufficiently high that he borrows from the rest of the world to finance investment above and beyond the amount of his savings. Domestic investment is then greater than national savings. Of course, if Juan lends to the rest of the world, then he will have extra resources in the future when those loans are repaid. If he borrows from the rest of the world, he will need to pay off that loan at some point in the future.

There may be very good opportunities in an economy that justify a lot of investment. In this case, it is worthwhile for an economy to borrow from other countries to supplement its own savings and build up the capital stock faster. Even though the economy will have to pay off those loans in the future, the benefits from the higher capital stock are worth it.

The circular flow of income shows us how these flows show up in the national accounts. If we are borrowing on net from other countries, there is another source of funds in additional to national savings that can be used for domestic investment. If we are lending on net to other countries, domestic investment is reduced.

Toolkit: Section 16.16 "The Circular Flow of Income"

You can review the circular flow of income in the toolkit.

investment = national savings + borrowing from other countries

or

investment = national savings − lending to other countries.

Savings and investment in a country are linked, but they are not the same thing. The savings rate tells us how much an economy is setting aside for the future. But when studying the accumulation of capital in an economy, we look at the investment rate rather than the savings rate. Total investment as a fraction of GDP is called the investment rate:

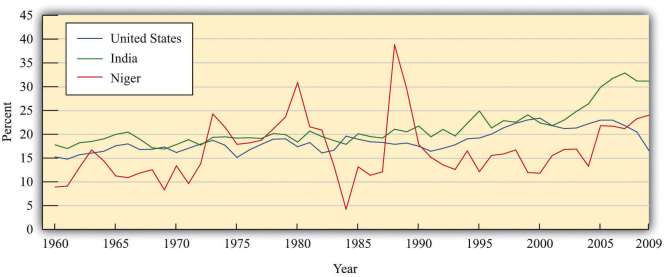

***Figure 6.7 "Investment Rates in the United States, India, and Niger" shows investment rates in the United States, India, and Niger from 1960 to 2009. A number of features of this picture are striking: [***International Monetary Fund, World Economic Outlook Database, April 2011, accessed July 29, 2011, http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2011/01/weodata/index.aspx.***]

- For most of the period, India had a higher investment rate than the other two countries. As we saw earlier, India was also the fastest growing of the three countries. These facts are connected: capital accumulation plays an important role in the growth process.

- The investment rate in the United States has been relatively flat over time, though it has been noticeably lower in recent years.

- Investment rates in Niger have been more volatile than in the other two countries. They were low in the mid 1980s but have increased substantially in recent years.

Low investment rates may be due to low savings rates. They may also reflect relatively low returns to increases in the capital stock in a country. The low investment rate that prevailed for many years in Niger not only reflected a low saving rate but also indicates that something is limiting investment from external sources. For the United States, in contrast, a significant part of the high investment rate is due not to domestic savings but to inflows from other countries.

We know that output per person is a useful indicator of living standards. Increases in output per person generally translate into increases in material standards of living. But to the extent that an economy trades with other countries, the two are not equivalent. If an economy borrows to finance its investment, output per person will exaggerate living standards in the country because it does not take into account outstanding obligations to other countries. If an economy places some of its savings elsewhere, then measures of output per person will understate living standards. [The national accounts deal with this issue by distinguishing between GDP, which measures the production that takes place within a country’s borders, and gross national product (GNP), which corrects for income received from or paid to other countries.]

- 2227 reads