So far, we have talked about buying foreign currencies to purchase either assets or goods and services. Another reason to buy foreign currencies is in the hope that you could make money by trading them. Let us think about how you might try to make money in the foreign exchange market. You might start with some dollars and exchange them for euros. Then you could take those euros and exchange them for dollars again. Is it possible that, by doing this, you could end up with more money than you started with? Could you buy euros cheaply and then sell them at a high price, thus making a profit?

Begin by supposing that dollars and euros are only two currencies in the world, and there are only two economies: the United States and Europe (a shorthand for “those European countries that use the euro”). Imagine that there are two separate markets: in the euro market, the price of 1 euro is $2; in the dollar market, the price of one dollar is EUR 1. With these two prices, there is money to be made by buying and selling currencies. Start with 1 euro. Sell that euro in the market for euros and obtain $2. Use those dollars to buy euros in the market for euros and obtain 2 euros. Now we are talking business: you started with 1 euro, made some trades, and ended up with 2 euros.

There is, of course, a catch. The prices that we just suggested would not be consistent with equilibrium in the foreign exchange markets. As we have just seen, there is a simple recipe for making unlimited profit at these prices, not only for you but also for everyone else in the market. What would happen? Everyone would try to capitalize on the same opportunity that you saw. Those with euros would want either to sell them in the euro market—because euros are valuable—or to use them to buy dollars in the dollar market—because dollars are cheap. Those with dollars, however, would not want to buy expensive euros in the euro market, and they would not want to sell them in the dollar market. Hence, in the euro market, the supply of euros would shift rightward, and the demand for euros would shift leftward. The forces of supply and demand would make the dollar price of euros decrease. In the dollar market, the supply of dollars would shift leftward, and the demand for dollars would shift rightward, causing the euro price of dollars to increase.

The mechanism we just described is arbitrage at work again. The arbitrage possibility between the dollar market for euros and the euro market for dollars disappears when the following equation is satisfied:

price of euro in dollars × price in dollar in euros = 1.

When this condition holds, there is no way to buy and sell currencies in the different markets and make a profit. As an example, suppose that EUR 1 costs $2 and $1 costs EUR 0.5. These prices satisfy the equation because 2 × 0.5 = 1. Imagine you start with $1. If you use it in the dollar market for euros to buy euros, then you will have EUR 0.50. If you then use these in the euro market for dollars to buy dollars, you will get $2 for each euro you supply to the market. Since you have half of a euro, you will end up with $1, which is what you started with. There is no arbitrage opportunity.

By now you have probably realized that there is a close connection between the market for euros and the market for dollars (where dollars are bought and sold using euros). Whenever someone buys euros, they are selling dollars, and whenever someone sells euros, they are buying dollars. In our two-country, two-currency world, the market for euros and the market for dollars are exactly the same market, just looked at from two different angles.

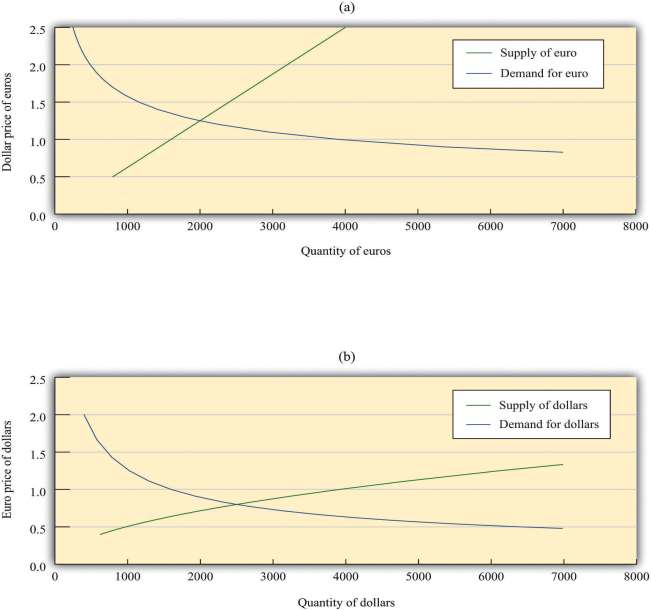

We illustrate this in . In part (a) of , we show the market where euros are bought and sold, and in part (b) of the market where dollars are bought and sold. The supply curve for dollars is just the demand curve for euros, and the demand curve for dollars is the same as the supply curve for euros. For example, suppose 1 euro costs $2. From part (a), we see that, at this price, people would supply EUR 3,200. In other words, there are individuals who are willing to exchange EUR 3,200 for $6,400. If we think about this from the perspective of the market for dollars, these people would demand $6,400 in the market when $1 costs EUR 0.50—and, indeed, we see that this is a point on the demand curve in part (b). The market is in equilibrium when EUR 1.00 costs $1.25, or equivalently when $1 costs EUR 0.80. At this exchange rate, holders of dollars are willing to give up $2,500, and holders of euros are willing to give up EUR 2,000.

- 3478 reads