Capital goods don’t last forever. Machines break down and wear out. Technologies become obsolete: a personal computer (PC) built in 1988 might still work today, but it won’t be much use to you unless you are willing to use badly outdated software and have access to old- fashioned 5.25-inch floppy disks. Buildings fall down—or at least require maintenance and repair.

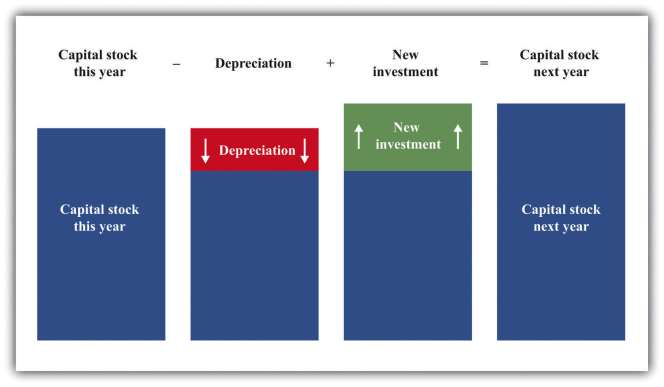

Depreciation is the term economists give to the amount of the capital stock that an economy loses each year due to wear and tear. Different types of capital goods depreciate at different rates. Buildings might stay standing for 50 or 100 years; machine tools on a production line might last for 20 years; an 18-wheel truck might last for 10 years; a PC might be usable for 5 years. In macroeconomics, we do not worry too much about these differences and often just suppose that all capital goods are the same. The overall capital stock increases if there is enough investment to replace the worn out capital and still contribute some extra. The overall change in the capital stock is equal to new investment minus depreciation:

change in capital stock = investment − depreciation of existing capital stock.

Investment and depreciation are the flows that lead to changes in the stock of physical capital over time. We show this schematically in ***Figure 5.9 "The Accumulation of Capital". Notice that capital stock could actually become smaller from one year to the next, if investment were insufficient to cover the depreciation of existing capital.

- 1981 reads