Almost universally, prices are quoted in terms of some currency, such as pesos, dollars, or euros. Goods and services sold in the United States have prices in terms of US dollars. The dollar serves as a unit of account. But when the very same goods and services are sold in Europe, they are priced in a different unit of account: euros. This role of money is so familiar as to be mundane, yet our economy simply could not function without a commonly accepted monetary measuring stick. It would be like building a house without an accepted measure of length or running an airline without an accepted measure of time.

The unit that people use to keep account of their monetary transactions varies from country to country. In Mexico, prices are quoted in pesos, in India prices are quoted in rupees, and so on. In most countries, the medium of exchange and the unit of account are the same thing, but this need not be true.

Because the US dollar is known throughout the world, it is often used as a unit of account in unexpected places. Prices of commodities in international transactions may be quoted in terms of the dollar even when the transaction does not directly involve the United States. Luxury hotels in China and elsewhere sometimes quote prices in US dollars even to guests who are not coming from the United States. [***In Chapter 3 "The State of the Economy", we discuss both nominal and real gross domestic product (real GDP). Nominal GDP is the value of all the goods and services produced in an economy, measured in terms of money. Money is used as a unit of account to allow us to add together different goods and services. Even the concept of real GDP uses money as a unit of account: the difference is that we use money prices from a base year to value output rather than current money prices.***] As another example, after the changeover to the euro, that currency became the medium of exchange and the “official” unit of account. But many people—at least in terms of their own thinking and mental accounting—continued to use the old currencies. In everyday conversation, people continued to talk in terms of the old currencies for months or even years after the change.[*** On a bike trip in the summer of 2002, one of the authors had lunch in a French country restaurant. Though it was many months after the change to the euro, the menu was still in French francs. An elderly lady running the restaurant painstakingly produced a bill in euros: for each entry (in French francs), she multiplied by the exchange rate (euros to francs) and then added the amounts together.***] Even today, some bills and bank statements in Europe continue to quote the old currency along with the euro.

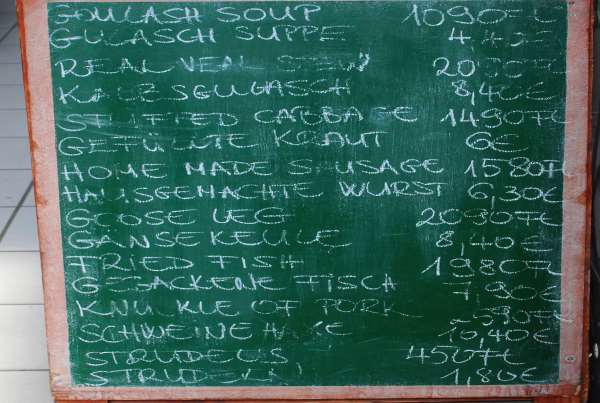

Meanwhile, merchants in countries who have not adopted the euro may still quote prices in that currency. In Hungary, the local currency is called the forint. ***Figure 9.3 "The Euro as a Unit of Account" shows a sign at a restaurant in Budapest, Hungary, advertising goods in both currencies: goulash soup, for example, is sold for 1,090 forint or 4.40 euro. If, as may well be the case, the restaurant is also willing to accept euros in payment, then the euro is also acting as a medium of exchange alongside the forint.

KEY TAKEAWAY

Fiat money has value because everyone believes it has value.

The three functions of money are medium of exchange, store of value, and unit of account.

***

Checking Your Understanding

In what sense are you a specialist in production and a generalist in consumption?

Why is money less effective as a store of value when inflation is high?

In times of inflation, money is also less effective as a unit of account. Why?

- 2138 reads