Growth accounting focuses on how inputs—and hence output—change over time. We use the tool both to look at changes in an economy over short time periods—say, from one month to the next—and also over very long time periods—say, over decades. We are limited only by the data that we have available to us. It is sometimes useful to distinguish three different time horizons.

- The short run refers to a period of time that we would typically measure in months. If something has only a short-run effect on an economy, the effect will vanish within months or a few years at most.

- The long run refers to periods of time that are better measured in years. If something will happen in the long run, we might have to wait for two, three, or more years before it happens.

- The very long run refers to periods of time that are best measured in decades.

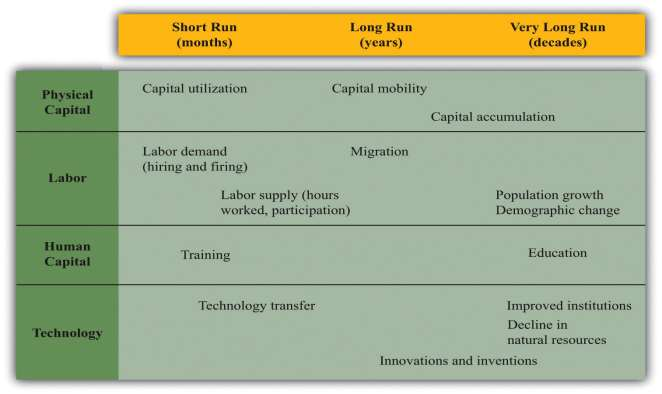

These definitions of the short, long, and very long runs are not and cannot be very exact. In the context of particular chapters, however, we give more precise definitions to these ideas. [***For example, Chapter 10 "Understanding the Fed" explains the adjustment of prices in an economy. In that chapter, we define the short run as the time horizon in which prices are “sticky”—not all prices have adjusted fully—whereas the long run refers to a period where all prices have fully adjusted. Meanwhile, Chapter 6 "Global Prosperity and Global Poverty" uses the very long run to refer to a situation where output and the physical capital stock grow at the same rate.***] ***Figure 5.11 "The Different Time Horizons in Economics" summarizes the main influences on the inputs to the production function in the short run, the long run, and the very long run.

Look first at physical capital—the first row in ***Figure 5.11 "The Different Time Horizons in Economics". In the short run, the amount of physical capital in the economy is more or less fixed. There are a certain number of machines, buildings, and so on, and we cannot make big changes in this capital stock. One thing that firms can do in the short run is to change capital utilization—shutting down a production line if they want to produce less output or running extra shifts if they want more output. Once we move to the long run and very long run, capital mobility and capital accumulation become important.

Look next at labor. In the short run, the amount of labor in the production function depends primarily on how much labor firms want to hire (labor demand) and how much people want to work (labor supply). As we move to the long run, migration of labor becomes significant as well: workers sometimes move from one country to another in search of better jobs. And, in the very long run, population growth and other demographic changes (the aging of the population, the increased entry of women into the labor force, etc.) start to matter.

Human capital can be increased in the long run (and also in the short run to some extent) by training. The most important changes in human capital come in the very long run, however, through improved education.

There is not very much that can be done to change a country’s technology in the short run. In the long run, less technologically advanced countries can import better technologies from other countries. In practice, this often happens as a result of a multinational firm establishing operations in a developing country. For example, if Dell Inc. establishes a factory in Mexico, then it effectively transfers some know-how to the Mexican economy. This is known as technology transfer, the movement of knowledge and advanced production techniques across national borders.

In the long run and very long run, technology advances through innovation and the hard work of research and development (R&D) that—hopefully—gives us new inventions. In the very long run, countries may be able to improve their institutions and thus create better social infrastructure. In the very long run, declines in natural resources also become significant.

KEY TAKEAWAY

Growth accounting is a tool to decompose economic growth into components of input growth and technological progress.

In economics, we study changes in GDP over very different time horizons. We look at short-run changes due mainly to changes in hours worked and the utilization of capital stock. We look at long-run changes due to changes in the amount of available labor and capital in an economy. And we look at very-long-run changes due to the accumulation of physical and human capital and changes in social infrastructure and other aspects of technology.

***

Checking Your Understanding

Rewrite the growth accounting equation for the case where a = 1/4.

Using the growth accounting equation, fill in the missing numbers in Table 5.2 "Some Examples of Growth Accounting Calculations*".

- 11635 reads