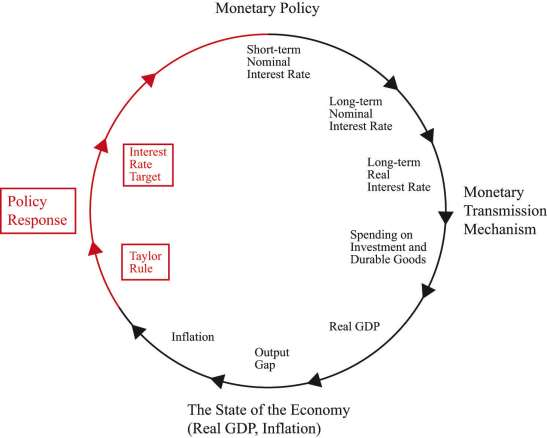

We have now traced the effects of monetary policy from interest rates to spending to real GDP to inflation. The effects of monetary policy do not stop there. Instead, as inflation adjusts in response to monetary policy, there is a feedback to interest rates through monetary policy itself. This is shown in ***Figure 10.14 "Completing the Circle of Monetary Policy".

Observers of the Fed’s behavior over the past 20 or so years have argued that the Fed generally follows a rule that makes its choice of a target interest rate somewhat predictable. The rule that summarizes the behavior of the Fed is sometimes called the Taylor rule; it is named after John Taylor, an economist who first characterized Fed behavior in this manner. [***Comments on John Taylor’s career and his contributions to monetary economics by Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke are available at “Opening remarks to the Conference on John Taylor’s Contributions to Monetary Theory and Policy, Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas, Dallas, Texas,” Federal Reserve, October 12, 2007, accessed September 20, 2011,http://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/speech/bernanke20071012a.htm. ***] The Taylor rule stipulates a relationship between the target interest rate and the state of the economy, typically represented by both the inflation rate and some measure of economic activity (such as the gap between actual and potential GDP). Usually, we think that the monetary authority operates with a lag so that the interest rate the monetary authority sets at a point in time reflects the output gap and inflation from the recent past. According to the Taylor rule, the Fed will increase real interest rates when

- inflation is greater than the target inflation rate,

- output is above potential GDP (a negative output gap).

Conversely, the Fed will decrease real interest rates when

- inflation is less than the target inflation rate,

- output is below potential GDP (a positive output gap).

The Fed will want to increase interest rates and thus “put the brakes on the economy” when inflation is high and when they think that real GDP is above its long-run level (potential output). The Fed will want to decrease interest rates when inflation is relatively low and the economy is in a recession.

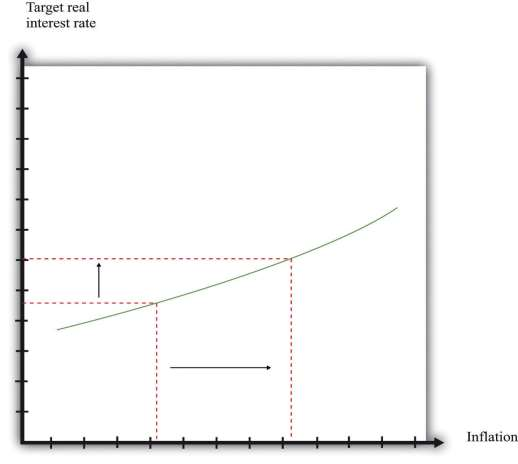

An example of a Taylor rule is shown in ***Figure 10.15 "The Taylor Rule". The vertical axis is the real interest rate target of the Fed, and the horizontal axis is the inflation rate. As the inflation rate increases, the Fed, according to this rule, then increases the interest rate.

The different pieces of the Taylor rule can be in conflict. For example, the Fed may face a situation where inflation is relatively high, yet the economy is in recession. The precise specification of the rule then provides guidance as to how the Fed trades off its inflation and output goals. The rule is largely descriptive: it summarizes in a succinct manner the actions of the Fed. In doing so, it allows individuals to predict with some accuracy what actions the Fed is likely to take in the future.

The Taylor rule describes Fed policy in terms of the real interest rate. We know, however, that the Fed actually targets a nominal rate. This has a surprising implication when we examine how the Fed responds to inflation. Suppose the Fed is currently meeting its target inflation rate—say, 3 percent—and the federal funds rate is currently 5 percent. The real interest rate is therefore 2 percent (remember the Fisher equation). Now suppose the Fed sees that inflation has increased from 3 percent to 4 percent. The increase in the inflation rate has the effect of decreasing the real interest rate—again, this comes directly from the Fisher equation. The real interest rate is now only 1 percent. Yet the Taylor rule tells us that the Fed wants to increase the real interest rate. To do so, it must increase nominal interest rates by more than the increase in the inflation rate. In our example, the inflation rate increased by one percentage point, so the Fed will have to increase its target for the federal funds rate by more than one percentage point—perhaps to 6.5 percent.

The Taylor rule completes the circle of monetary policy. As indicated by ***Figure 10.14 "Completing the Circle of Monetary Policy", the monetary policy rule links the state of the economy, represented by the inflation rate and the output gap, to the interest rate. There is usually a lag in the response of the Fed to the state of the economy. So, for example, the decision made at the FOMC meeting in February 2005 reflected information on the state of the economy through the end of 2004, at best.

- 2373 reads