Imagine a series of three visitors traveling from the United States to Europe. First, we have someone arriving on vacation. Chances are that she will want to exchange dollars for euros to have money to spend on hotels, meals, and so on. She also buys souvenirs in Europe—goods that she imports back to the United States. Our second visitor spends a lot of time in Europe for work purposes. He might open a bank account in, say, Germany. If he wanted, he could use this bank account to keep some of his wealth in Europe. He would buy euros with his dollars, deposit these euros in the bank to earn interest, and then—at some point in the future—he would take his money out of the bank in Germany and exchange the euros for dollars. (Later, we will consider how you can decide if this is a good investment strategy. For now, our point is that this type of financial investment is another source of demand for euros.) Our third visitor to Europe is a professional wine buyer who wants to purchase wine to sell in a US restaurant. She travels to the wine-growing regions of Europe (France, Spain, Italy, Germany, Portugal, etc.) and must exchange dollars for euros to pay for her purchases.

Our three visitors represent a microcosm of the transactions that take place in the foreign exchange market every day. Households and firms buy euros to pay for their imports of goods and services (souvenirs, wine, etc.). Many different goods and services are produced in Europe and sold in the United States. Some are imported by retailers, others by specialist import-export firms, and still others by individuals, but in all cases there is an associated purchase of euros using dollars.

The demand for euros also arises from financial investment by households, firms, and financial institutions. For example, a wealthy private investor in the United States may purchase stock issued by a company in Europe. To buy that stock, the US investor sells dollars and buys euros. In practice, such transactions are typically carried out by financial institutions that undertake trades on behalf of households and firms.

Most exchanges of dollars for euros do not actually entail someone traveling to Europe. Think about the foreign currency needs of a large multinational firm that produces goods and services in Europe but sells its output in the United States. The company naturally needs euros to pay workers and suppliers in Europe. Since it sells goods and thus earns revenues in dollars, the company must convert from dollars to euros very frequently. But you will not see the company’s chief financial officer in an airport line to exchange money. Instead, such currency operations are conducted through financial institutions, such as commercial banks.

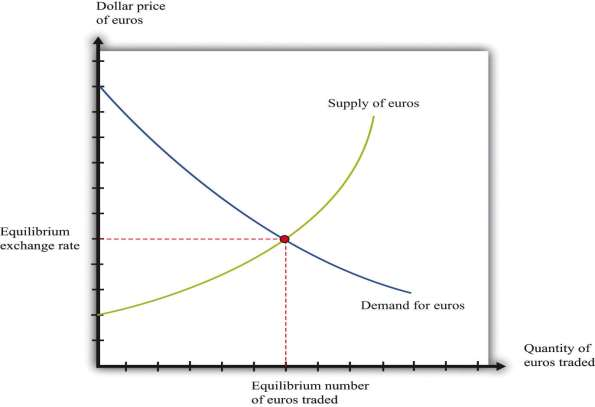

Because of all these transactions, there are very active and sophisticated markets in which currencies are traded. We can represent these markets using the familiar supply-anddemandframework. shows a picture of the market where euros are bought and sold. Buyers from the United States buy euros with dollars, and European traders sell euros in exchange for dollars. [***Of course, it is not literally the case that everyone who is buying is from the United States and that everyone selling is from Europe. If you have dollars, you can buy euros; if you have euros, you can sell them for dollars. But it is simpler to explain if we think of Europeans selling euros and Americans buying them.***] The supply and demand curves refer to the object being traded—euros. Thus the quantity of euros is shown on the horizontal axis. The price on the vertical axis is in dollars.

This market is just like any other you encounter. The demand curve is downward sloping: as the price of euros increases, the quantity of euros demanded decreases. This is the law of demand at work. As the price of euros increases, people in the United States will find that goods and services produced in Europe are more expensive. For example, suppose that 1 euro costs $1, and a Mercedes automobile costs EUR 50,000. [***There is an established set of three-letter symbols for all the currencies in the world. Euros are denoted by EUR, US dollars are denoted by USD, Australian dollars are denoted by AUD, and so forth. In this book we use the familiar $ symbol for US dollars and the three-letter symbols otherwise. A list of the currency codes can be found at http://www.xe.com/iso4217.php.***] Then its cost in dollars is $50,000. Now imagine that euros become more expensive, so that EUR 1 now costs $2. You now need $100,000 to buy the same Mercedes in Europe. So an increase in the price of euros means that Americans choose to buy fewer goods and services produced in Europe. Exactly the same logic tells us that an increase in the price of the euro makes European assets look less attractive to investors. A German government bond, a piece of real estate in Slovenia, or a share in a Portuguese firm might look like good buys when the euro costs $1 yet seem like a bad idea if each euro costs $2.

The supply curve also has a familiar upward slope. As the price of euros increases, more people in Europe sell their euros in exchange for dollars. They do so because with the higher dollar price of euros, they can obtain more dollars for every euro they sell. This means that they can buy more US goods and services or dollar-denominated financial assets.

The price where supply equals demand is the equilibrium exchange rate. (The market also shows us the equilibrium number of euros traded, but here we are more interested in the price of the euro.)

Toolkit:

The foreign exchange market is an example of a market that we can analyze using the tool of supply and demand. You can review the supply-and-demand framework and the meaning of equilibrium in the toolkit.

- 1462 reads