Suppose you do not want to spend your $100 until next year. You could just put the money under your mattress, but a better option is to find some way of getting more than $100 next year. One way to do this is to lend your money to someone else. For you, this might simply mean taking it to your bank and putting it in your savings account. When you do that, you are making a loan to the bank. Of course, the bank probably will not leave the money in its vault; it will lend that money to someone else. Banks and other financial institutions act as intermediaries between those who want to save and those who want to borrow.

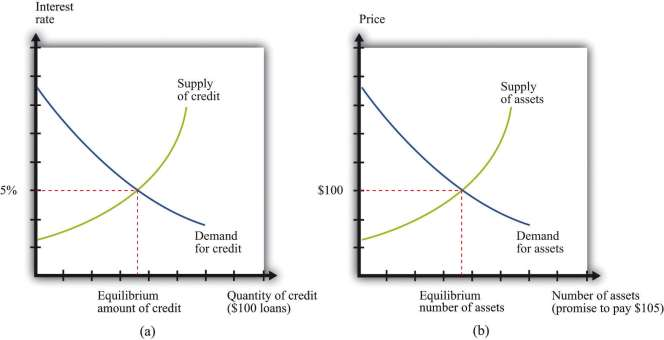

The credit market brings together the suppliers and demanders of credit, and the nominal interest rate is the price that brings demand and supply into balance. The supply of credit increases as the interest rate increases: as the return on saving increases, households will generally save more and thus supply more funds to the credit market. The demand for credit decreases as the interest rate increases: when it is expensive to borrow, households and firms will borrow less. At the equilibrium interest rate, the quantity of credit supplied and the quantity of credit demanded are equal. This is shown in part (a) of ***Figure 9.9 "The Credit Market and the Asset Market".

There is another way to look at credit markets. Borrowers get money today in exchange for a promise to pay money later. Lenders purchase those promises by giving up money today. Instead of asking how much the interest rate is for a given $100 loan, we could ask what people would be willing to pay today for the right to receive $105 in a year’s time.

The market for the promise to pay $105 in a year is illustrated in part (b) of Figure 9.9 "The Credit Market and the Asset Market". The units on the horizontal axis are $105 payments. These are assets: buyers are purchasing a piece of paper that is a promise to deliver $105 in a year’s time. The price on the vertical axis is the current price of that asset.

The nominal rate of return on an asset is the amount that you obtain, in percentage terms, from holding the asset for a year. In the case of the simple one-year asset we are considering, the return is given as follows:

We can also rearrange this to give us the price of the asset:

Notice what happens when we look at the market in this way. Buyers have become sellers, and sellers have become buyers. Borrowers are sellers: they sell the promise to pay. Lenders are buyers: they purchase the promise to pay. If we are looking at the same group of buyers and sellers as before, then the current equilibrium price of this asset would be $100.

The nominal interest rate and the nominal rate of return defined through these two markets must be the same. If not, there would be an arbitrage possibility. Imagine, for example, that the interest rate is 5 percent but the price of the asset is $90. In this case, the rate of the return on asset is 11090−1, which is 22.2 percent. So you could make a lot of money by borrowing at a 5 percent interest rate and then purchasing the promises to pay $110 at price of $90.

If you could do this, so also could many major financial institutions—except that they would operate on a much larger scale, perhaps buying millions worth of assets and borrowing a lot in credit markets. So the demand for credit would shift outward, as would the demand for assets. This would cause the interest rate to increase and the asset price to increase, so the rate of return on the asset decreases. This would continue until the arbitrage opportunity disappeared.

In summary, we would say there is no arbitrage opportunity when the

nominal rate of return on asset = nominal interest rate.

The rate of return on the asset, in other words, is equivalent to the interest rate on the asset. Equivalently this means that

In the second line we replaced (1 + nominal interest rate) with the nominal interest factor. The two are equivalent, but sometimes we find it more convenient to work with interest factors rather than interest rates.

The argument that we have just made should seem familiar. It is analogous to the argument for why there cannot be distinct dollar-euro and euro-dollar markets; they are just ways of looking at the same asset. Likewise, we can think of the sale of any asset as equivalent to borrowing, while for any example of credit we can also think of there being an underlying asset.

- 1448 reads