To understand in more detail why interest rates affect spending on durable goods, consider the purchase of a machine by a firm. Firms carry out such investment spending because they expect the machine to yield a flow of profits not only in the present but also for several years into the future. A machine is a capital good; it is used in the production of other goods and is not used up during the production process. The fact that the returns from the machine accrue over several years is what we mean by the term durable. It is not correct to simply add profit flows in different years because a dollar today is usually worth more than a dollar next year. Why? If you take a dollar today and put it in a savings account at the bank, you will get your dollar plus interest back next year. If the interest rate is 10 percent, then $1 this year is worth $1.10 next year. Turning it around, $1 next year is worth only about 91 cents this year (because 1/1.1 = 0.91).

The technique for adding together flows of resources in different periods is called discounted present value. To work out whether a given investment is profitable, a firm must calculate the value, in today’s terms, of the flows of profits that it expects to receive. It then compares this to the cost of the investment. If the discounted present value of the profits exceeds the cost, the firm will undertake the investment.

Toolkit: Section 16.3 "Discounted Present Value"

You can review discounted present value in the toolkit.

Table 10.1 "Return on Investment" illustrates a simple investment decision. In year 1, you pay for a machine, and it yields some profit in that year. The next year, the machine yields further profit. Suppose you, as a manager of a firm, must decide whether or not to buy this machine. How do you make this decision? In the first year, you pay $970 for the machine and earn only $500 back, so you are down $470. In the second year, you will earn an additional $500—but you have to wait a year to get this money. Think of the profits in year 2 as being in real terms— that is, already corrected for inflation.

Table 10.1 Return on Investment

|

Year |

Payment for |

Real Profit from |

|

Machine |

Machine |

|

|

1 |

970 |

500 |

|

2 |

0 |

500 |

To decide about the purchase of the machine, you need to know the interest rate. If the interest rate were zero, the calculation would be easy. You could just add together the profit flows in the 2 years, observe that $1,000 is more than the $970 that you have to pay for the machine, and conclude that the purchase is a good idea. Now suppose the real interest rate is 5 percent, which means that the real interest factor is 1.05. Then the discounted present value of the profit flows from the machine is given by the following equation:

In this case, the purchase is still a good idea. You will earn $976 in present value terms, exceeding the $970 that you have to pay, so you still come out ahead.

But what if that the real interest rate is 10 percent? In this case,

This is less than the amount that you had to pay for the machine. The investment no longer looks like a good idea. The higher the interest rate, the more we must discount future earnings, so the less likely it is that a current investment will be profitable.

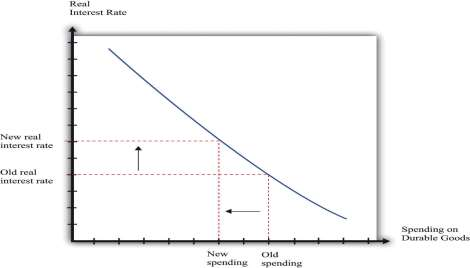

In most real-life cases, the flow of profits extends for several years, so the discounted present value calculation is somewhat harder. (Still, even harder calculations can be done easily with a calculator or a spreadsheet.) Our example may be simple, but it illustrates our key point. As the real interest rate decreases, the discounted present value of profits from a machine increases. In the economy, there are at any given time many possible investment opportunities. Some have higher profit flows than others. At lower interest rates, more machines will be profitable to purchase: investment increases as the real interest rate decreases.

Households purchase homes and durable consumption goods, such as cars and household appliances. If the household borrows to make such purchases (through mortgages, car loans, or other personal loans), then exactly the same logic applies. Higher interest rates will tend to deter the household from these purchases, whereas lower interest rates will encourage purchases. [***Even if the household uses its own accumulated saving to buy the durable good, there is an opportunity cost of using these funds: it could have put the money in the bank instead. The higher the real interest rate, the better it looks to put money in the bank.***] Households usually have some choice about when exactly to purchase such goods. If interest rates are high this year, it probably makes sense to put off that purchase of a new washing machine until next year, when rates might be lower.

The effect of an increase in the real interest rate on spending on durable goods is captured in Figure 10.7 "The Relationship between the Real Interest Rate and Spending on Durable Goods".

- 1724 reads