We have talked about arbitrage with goods and arbitrage with foreign currencies. We can also put the two together to study the prices of goods that are traded across international borders. Arbitrage of goods from one country to another is a bit more complicated because it involves buying and selling currencies as well as goods. To see how this works, imagine you are going on a trip to Europe. You are allowed two suitcases filled with belongings free of charge on the airplane. What about filling a suitcase full of new blue jeans, transporting them to Europe, and then selling them there? Could you make money that way?

Suppose that the dollar price of 1 euro is $1.50. Further, suppose that the price of a pair of blue jeans is $70.00 in the United States and EUR 50.00 in Paris. Consider the following sequence of actions.

- Take $70 out of your pocket and buy a pair of blue jeans.

- Travel with these blue jeans to Paris.

- Sell the jeans for euros.

- Buy dollars with your euros.

The question is whether you can make money in this way. The answer is given by how many dollars you will have in your pocket at the end of these steps. When you sell the jeans in Paris, you will have EUR 50.00. If the dollar price of euros is $1.50, then by selling the jeans in Paris you will get 50 × $1.50 = $75. This is a profit of $5 for each pair of jeans—you are in business.

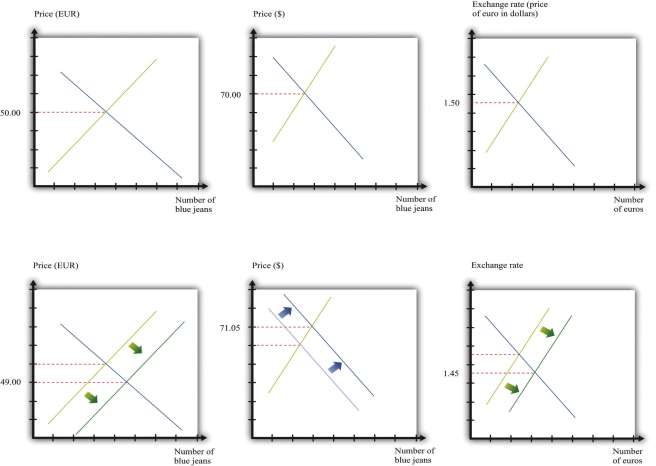

Once again, the opportunity for arbitrage suggests that this situation is unlikely to persist. Entrepreneurs will buy jeans in the United States, take them to Paris, and sell them there. Market forces in three different markets will work to eliminate the profit. First, the activity of arbitrageurs will increase the demand for jeans in the United States, causing the US price of jeans to increase. Second, the increased supply of jeans in Paris will cause the price there to decrease. And third, there will be an increased supply of euros in the foreign exchange market, which will cause the euro to depreciate. This is shown in.

These price changes continue until there are no profits to be made by arbitrage. Exactly how much of the adjustment will take place in each market depends on the slopes of the supply and demand curves. In , we have drawn the new equilibrium as follows: blue jeans cost EUR 49 in Europe and $71.05 in the United States; and the exchange rate is $1.45 per euro. At these prices,

price of blue jeans in dollars = price of blue jeans in euros × price of euro in dollars,

and there is no longer any possibility of arbitrage. This is another illustration of the law of one price. If we were literally talking just about arbitrage in blue jeans, most of the adjustment would take place in the markets for blue jeans in the United States and Europe, and there would be a negligible effect on the exchange rate. But if the same kinds of arbitrage opportunities exist for lots of goods, then there will be an impact on the exchange rate as well.

For tradable goods, the law of one price says that the

dollar price of good = euro price of good × dollar price of euro.

When this condition holds, there are no arbitrage profits to be gained by purchasing the good with dollars, selling it for euros, and then buying dollars with euros. Likewise, if this condition holds, there are also no arbitrage profits from purchasing the good with euros, selling it for dollars, and then buying euros with dollars. In general, we expect that such arbitrage will occur very quickly. There are no profits to be made from arbitrage when the law of one price holds.

The Economist has kept track of the price of a McDonald’s Big Mac in a number of countries for many years, creating something they call the “the Big Mac index.” contains some of their data. The last column of gives the price of a Big Mac in each selected country in July 2011, converted to US dollars at the current exchange rate. That is, the last column is calculated by dividing the local currency price (the second column) by the exchange rate (the third column). A Big Mac costs $4.07 in the United States but more than twice as much in Norway. China is a real deal at only $1.89.

Table 9.1 The Economist’s Big Mac Index, July 2011

|

Country |

Local Currency Price of Big Mac |

Local Currency Price of a Dollar |

Price in US Dollars |

|

United States |

USD 4.07 |

1 |

4.07 |

|

Norway |

NOK 45 |

5.41 |

8.31 |

|

Euro Area |

EUR 3.44 |

0.70 |

4.93 |

|

Czech Republic |

CZK 69.3 |

17.0 |

4.07 |

|

China |

CNY 14.7 |

6.45 |

1.89 |

Source: “The Big Mac Index: Currency Comparisons, to Go,” Economist online, July 28, 2011, accessed August 2, 2011,http://www.economist.com/blogs/dailychart/2011/07/big-macindex.

The price differentials in this table violate the law of one price: there is (apparently) profit to be made by buying Big Macs at a low price and selling them at a high price. Applying the principle of arbitrage, we should all be flying to China, buying Big Macs, traveling to Norway, and selling them on the streets of Oslo. Of course, there are a few small problems with this scheme, such as the following:

- It is expensive to fly back and forth between China and Norway.

- There is a limited capacity for transporting Big Macs on the airplane.

- The quality of the Big Mac might deteriorate while it is being transported.

- You might not be permitted to import meat products from China into Norway.

- You might have to pay taxes when you bring Big Macs into Norway.

- It might be tough to open a McDonald’s in Oslo.

This long list easily explains the deviations from the law of one price for Big Macs. Similar considerations explain why the law of one price might not hold for other goods. The law also does not apply to services, such as tattoos, since these cannot be imported and exported. The law of one price is most applicable to goods that are homogeneous and easily traded at low cost. Economists use the law of one price as a guide but certainly do not expect it to hold for all products in all places.

- 4379 reads