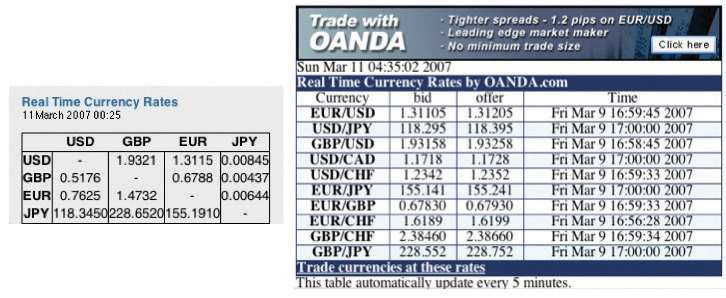

We live in a world with many different currencies, not just two. shows some exchange rates from http://www.oanda.com, a site that provides current and historical data on exchange rates and that is also an online market where you can trade currencies. So, on March 11, 2007, just after midnight, the price of a euro in dollars was 1.3115. At the same time, the price of a dollar in British pounds was 0.5176.

If you look at the table on the left side of , you see that it provides both the dollar price of the euro and the euro price of the dollar (and similarly for the other currency pairs). Tables such as this one have already built in the arbitrage condition, so you cannot keep buying and selling the same currency in exchange for dollars and make money.

When there are multiple currencies, we can imagine more complicated trading strategies. As an example, consider the following string of transactions.

- Take a dollar and use it to buy euros.

- Take the euros and buy Japanese yen.

- Take the yen and buy dollars.

If you end up with more than $1, then there are profits to be made buying and selling currencies in the manner outlined here. Can you make a profit this way? The answer, once again, is no. If you could, then the markets for foreign currency would not be in equilibrium: everyone would buy euros with dollars, sell them for yen, and then sell the yen for dollars. Once again, exchange rates would rapidly adjust to remove the arbitrage opportunity.

To verify this, let us go through this series of transactions using . One dollar will buy you EUR 0.7625. Now take these and use them to buy yen. You will get 0.7625 × 155.1910 = JPY 118.3331. Now, use these yen to buy dollars, and you will get 118.3331 × 0.00845 = $0.9999. You start with $1; you end with $1 (give or take a rounding error).

These calculations assume that there are no costs to trading foreign currencies. In practice, there are costs involved in these exchanges. A traveler arriving at an airport in need of local currency does not see rates posted as in the left-hand table in . Instead, they see something that looks like the right-hand table, where rates are posted in two columns: bid (buying) and offer (selling). The bid is a statement of how much the currency seller is willing to pay in local currency for the listed currency. The offer column is the price in local currency at which the seller is willing to sell to you. Naturally, the offer price is bigger than the bid: the seller buys currencies at a low price and sells them at a high price. The difference between the bid and offer prices is called the spread. The existence of the spread means that if you try to buy and sell currencies with the dealer, you will actually lose money. At the same time, the spread creates a profit margin for the dealer and thus pays for the service that the dealer provides.

- 1569 reads