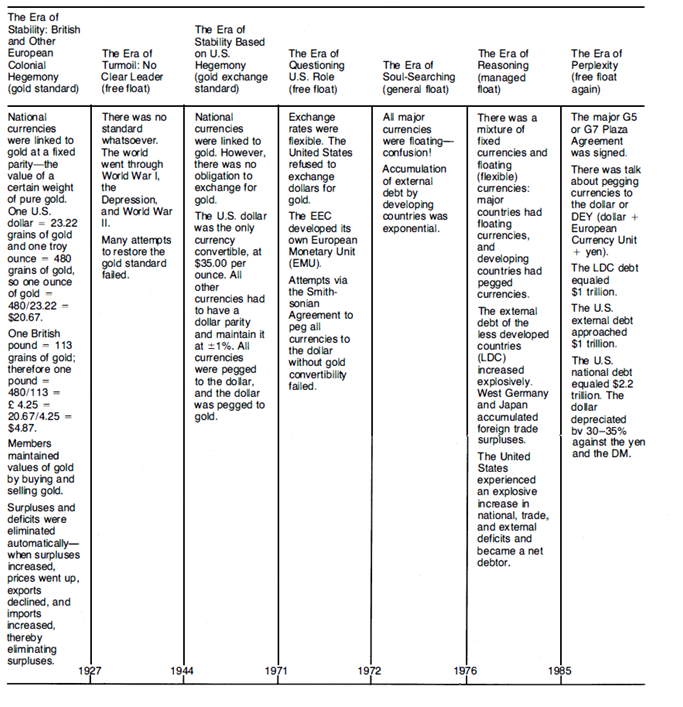

At the end of the Second World War, the United States was virtually the world's sale wealth holder, consumer, and, most importantly, capital goods producer. The U.S. dollar seemed to be the only currency worth accepting in international transactions and holding as a reserve. So it surprised no one that the rest of the world enthusiastically accepted an American initiative to restructure the International Monetary System. Representatives of 44 nations met at Bretton Woods, New Hampshire, in 1944 and agreed to establish an International Monetary System that would be immune to individual countries' currency manipulations and would guarantee a free flow of goods and money around the globe.

The Bretton Woods conference created the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD ), commonly known as the World Bank. It was agreed that the IMF would guarantee stability in exchange rates, and the World Bank would provide financial and expert assistance to countries that needed capital for their economic development.

All participating countries agreed to try to maintain the value of their currencies within 1 percent above or below the official parity by selling foreign currencies or gold if necessary. If its currency became too weak to defend, a country could devalue it by up to 10 percent without formal approval from the IME Larger devaluations needed the official approval of the IME

The u.s. dollar was given special status as an international reserve currency. The United States agreed to convert dollars held by foreigners into gold upon request, at the official price of $35 per ounce. Thus, the fixed exchange rate system was essentially a system in which all countries "pegged" their currencies to the dollar and the dollar was pegged to gold. It is for this reason that the system is also known as the adjustable peg system. Although gold was still the king, so to speak, it was the dollar that was the pivot of the International Monetary System.

This system, which depended on the central role of the United States and its dollar, worked remarkably well for over 20 years. The postwar years were, however, unlike any previous era. The period witnessed dramatic economic activity in Europe and Japan and a substantial decline in the relative position of the United States in the world economy. This unprecedented expansion in international economic activity revealed one of the most obvious weaknesses of the Bretton Woods system. The system was designed essentially to prevent "sickness" and to assist "sick" currencies. The system did not provide for problems on the international financial scene that arose from some countries' being extremely "healthy" and accumulating surpluses that they did not have to "return" to the International Monetary System. Continuing surpluses drained needed funds from the system, thereby creating a large liquidity shortage in the international financial system. Thus, countries with deficits could not find dollars with which to pay. Even the IMF and the World Bank fell victim to this liquidity drought.

The hoarding of dollars by countries with surpluses, combined with the outflow of dollars in the form of direct foreign investment and the migration of dollars to the Eurodollar market, created a tremendous liquidity shortage in the United States. At the same time the war in Viet Nam strained the U.S. Treasury. The result was a loss of confidence in the United States on the part of European countries. This loss of confidence led to a massive unloading of the dollars held by countries with surpluses. The U.S. Treasury was unable to accommodate the sudden substantial increase in the demand for gold. By 1971 the U.S. gold stock had dropped to $11 billion, down from $24 billion in 1948. Then, since the United States had most of the gold, it decided to change the rules.

The first step in changing the rules of the fixed exchange-rate system was taken in 1968, when the United States suspended the sale of gold to industrial users. This step proved to be insufficient to solve the gold-drain problem, and on August 15, 1971 the United States was finally forced to stop selling gold altogether. This action drove the final nail into the coffin of the fixed exchange rate system.

- 3280 reads