There are two versions of the Comparative Advantage Theory: the one-factor theory, which assumes a single factor of production, usually labor, and the two-factor theory, which is based on two factors, usually labor and capital.

The Ricardo Model: The Labor Theory of Value (One-Factor Theory). Ricardo's Labor Theory of Value states that the value of any product is equal to the value of the labor time required to produce it. For example, if a computer requires one month to construct and an automobile requires one year to construct, the price of the car will be twelve times that of the computer. Over a century ago the British economist David Ricardo used this idea in constructing his version of the theory of comparative advantage. According to the principle of comparative advantage, a country will produce and export products that it can produce with less labor time than is used by foreign countries and will import those products for which it requires a greater amount of labor time than is used by foreign countries.

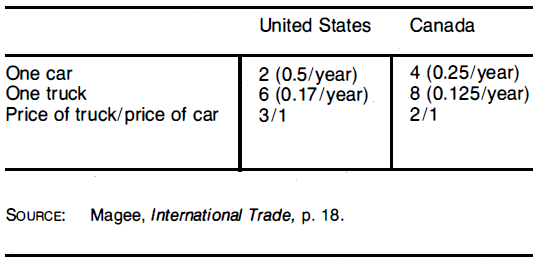

Figure 7.2 depicts hypothetical labor times required for the production of cars and trucks in the United States and Canada. In this example, the United States can produce one car with two worker-years, whereas Canada needs to spend twice as much labor time to produce the same car. On the other hand, the United States is only a bit more efficient than Canada in the production of trucks. Thus, according to Ricardo's theory, Canada will produce only trucks for its own consumers and for the United States, and the United States will produce only cars for its own customers and for the Canadians. Before international trade is instituted between the United States and Canada, the price of trucks relative to cars will be 3/1 in the United States, whereas it will be only 2/1 in Canada. But, as noted in the discussion of the Principle of the Positive Sum Game, one of the advantages of international trade is that it tends to reduce prices across international markets. Therefore, once international trade begins, prices of cars in Canada and trucks in the United States will begin to fluctuate downward until eventually they are pushed together in the two markets. That is, Canadians will sell their trucks to the United States, thereby pushing the price of U.S. trucks below the 3/1 ratio, and Americans will go to Canada to buy their trucks, thereby raising the price above the 2/1 ratio to, say, 2.7/1. These relationships will develop as long as each partner is sufficiently large to affect the prices in the other's market.

In this hypothetical situation the United States has a comparative advantage over Canada in the production of both products. As the exhibit shows, the United States is twice as efficient as

Canada in the production of cars and  times as efficient in

the production of trucks. In international trade language we say that the United States has an absolute comparative advantage over Canada. This situation might seem to suggest that it

would pay the United States to produce both cars and trucks and not engage in international trade. Ricardo's major contribution was to debunk this myth of absolute advantage.

times as efficient in

the production of trucks. In international trade language we say that the United States has an absolute comparative advantage over Canada. This situation might seem to suggest that it

would pay the United States to produce both cars and trucks and not engage in international trade. Ricardo's major contribution was to debunk this myth of absolute advantage.

To prove that it is not advantageous to refrain from international trade, we need only demonstrate that workers in the United States are better off with international trade than without it. Without international trade an American worker who can produce one car in 2 years would have to work 12 years (and produce six cars) in order to purchase two trucks in the United States (since the ratio of trucks to cars is 3/1). With the same six cars, the U.S. worker can buy three trucks in Canada (where the ratio of trucks to cars is 2/1). Thus, even though U.S. workers are superior to Canadian workers in producing both products, it pays them to specialize in the item in which they have the greatest relative advantage (cars) and trade that item in Canada for trucks.

The Heckscher-Ohlin Theorem (Two-Factor Theory). Despite its conceptual neatness and empirical verification, Ricardo's model cannot realistically be expected to explain all the complexities of international trade in terms of a single factor of production. The Heckscher-Ohlin model recognizes that more than one factor is needed to produce a given product and suggests that a country will export those products that require more of the factor it has in abundance. Capital-abundant countries will export products that use a lot of capital in their production—that is, capital-intensive products—and labor-abundant countries will export labor-intensive products. Cars are an example of a product that is more capital-intensive than labor-intensive. Chemicals are even more capital-intensive than cars. In both cases large sums of money must be invested in facilities and expensive equipment. Tomato growing, on the other hand, is a much more labor-intensive process than the production of either cars or chemicals.

Returning to the previous example of car and truck production in the United States and Canada, assume that cars are more capital-intensive than trucks: three units of capital are required to assemble a car, as compared to two units of capital to assemble a truck. Assume further that the United States has more capital per worker than does Canada. According to the Heckscher-Ohlin theorem, the United States will export its factor-abundant (capital-intensive) product, cars, and Canada will export its factor-abundant (labor-intensive) product, trucks.

Recall that in the Ricardo model, each country specializes in the production of only one product with which it has a relative comparative advantage. In the Heckscher-Ohlin model, both countries will produce both goods after free trade has been instituted. Thus, even though the United States is importing trucks from Canada, it will still satisfy some of its demand through local truck production. Canada will of course do the same for cars.

The Heckscher-Ohlin theorem has been studied by a number of economists, and some of the studies have corroborated the theorem. Stolper and Rosekamp, for example, found that West Germany, a capital-abundant country, exports capital-intensive goods; Bharadwaj found that, as would be expected, India exports labor-intensive goods. Other studies, however, have not supported the Heckscher-Ohlin theorem. Ichimura and Tatemoto found that Japan, a labor-abundant country, exports some capital-intensive goods; Wahl found Canada, a capital-abundant country, exporting labor-intensive goods. 1

Despite the considerable amount of divergent evidence, the Heckscher-Ohlin theorem does appear at least partially to explain international trade. Some studies, for example, have found that the so-called Leontief paradox—the fact that the United States, a capital-abundant country, nonetheless exports products that are labor-intensive—disappears when one considers that the type of labor used in the production of these products is skilled labor. Thus it can be said that the United States exports skill-intensive products and imports low-skill products. Of course, it takes capital to convert unskilled labor into skilled labor, so the Heckscher-Ohlin theorem still holds.

- 2693 reads