Industrialization is the process of creating wealth via the transformation of primary products, such as agricultural products and minerals, into marketable products. Although industry, broadly defined, includes manufacturing, mining, construction, the production of electricity, and the supplying of gas and water, this chapter focuses on manufacturing-the largest and most volatile industrial sector. 1

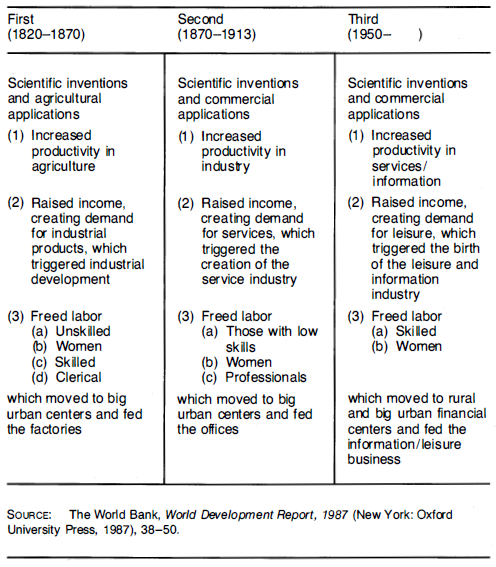

Industrial developments usually follow scientific discoveries. By applying these discoveries to satisfy human needs, humans are able to do more with less. When the industrial application of scientific discoveries reaches the point of affecting life to a large degree, an industrial revolution is said to have occurred. Thus far, humanity has undergone three industrial revolutions (see Figure 13.2).

The First Industrial Revolution started in Britain early in the nineteenth century, when innovations in the processes of spinning and weaving cotton greatly boosted productivity and output. This revolution is erroneously attributed to the introduction of machinery. The true source of the increases in productivity and output, however, was the emphasis on Adam Smith's principles of specialization and division of labor. Scientific discoveries in physics (such as the steam engine, which sparked the transport and mechanization revolution) came later. The First Industrial Revolution is generally defined as the period between 1820 and 1870.

The Second Industrial Revolution spanned the years from 1870 to 1913. During that time technological advances became more dependent on scientific research conducted by firms and universities specifically for commercial application. Germany (which was at the time a unified country) and later the United States led the way. The revolution focused primarily on the production of consumer goods, demand for which was fueled by the increase in liquidity ( disposable income) created by the increase in productivity in the agricultural sector. Fed with supplies from overseas, the Second Industrial Revolution created two worlds: the industrial league, made up of the countries engaged in heavy industrial production, and the suppliers of raw materials, consisting primarily of the colonies of European countries and the United States.

The fifties ushered in a new era of industrialization. Postwar reconstruction and growth in manufacturing were fueled by an explosion of new products and new technologies, liberalization of international trade, and increasing integration of the world economy. This Third Industrial Revolution, which began with mass assembly, synthetic raw materials, nuclear energy, jet aircraft, and electronic devices for entertainment and business use, is currently reaching a climax with supersonic travel, super speed computers, and superconductive processes. By creating an electronic network that provides instant connectedness, the Third Industrial Revolution has led to the globalization of industrialization. Now the world is divided into two types of manufacturing industries: the so-called traditional industries and the high-technology industries. 2

The traditional industries have generally been associated with fairly labor intensive technologies. Because of the low wage rates in the Third World and the relatively low cost of establishing facilities, these industries have been on the leading edge of export manufacturing in developing countries.

The high-tech industries, on the other hand, depend on access to the specialized resources required for research and development and for highly complex production processes. These industries have therefore been located in the industrial countries. As products mature, technology diffuses and production moves to more competitive locations abroad. (This phenomenon corresponds to the product-cycle theory of international trade first advanced by Raymond Vernon in 1966.)

Three main developments have marked the pattern of global industrialization in the postwar period:

- The appearance of a nonmarket alternative to industrialization-a service and information industry-in Eastern Europe and elsewhere

- Decolonization in Asia, Mrica, and the Caribbean

- The rise to prominence of the multinational corporation in world production and trade of manufactured items

The last four decades of experience with industrialization have taught the world some very important lessons. It is imperative that the student of international business and the international manager understand these lessons well, for they represent the canvas on which the tapestry of international production strategy is woven (see Table 13.1).

|

What are the lessons to be drawn from experiences of countries that have followed a successful path to industrialization?

|

| SOURCE: The World Bank, World Development Report, 1 987, pp. 54-57. |

- 2711 reads