|

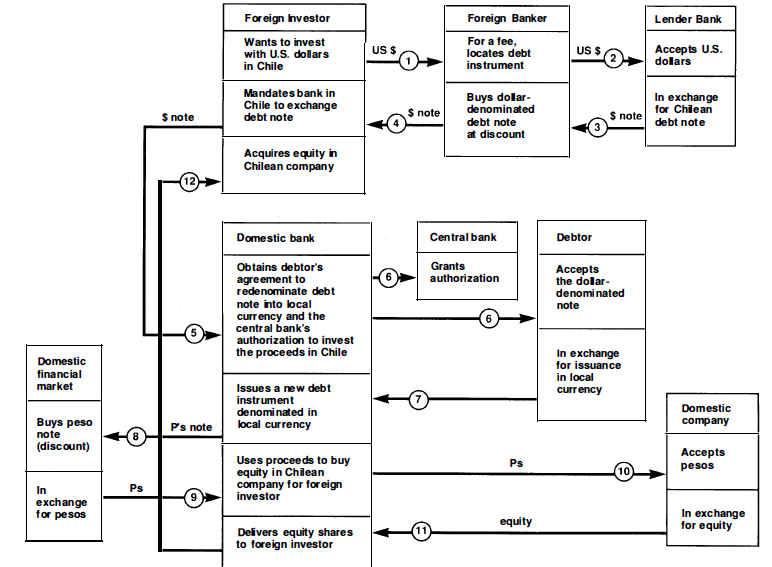

The existing exposure of commercial banks to developing countries is a key constraint to new spontaneous lending. Recently, a secondary market trading developing countries' debt instruments at a discount has emerged. The volume of transactions was initially quite limited, and price quotations on the discounted debt have been regarded as rather artificial in view of the thinness of the market. The market is becoming better organized, participation has widened, and the variety of transactions has increased. New interpretations of accounting and banking regulations in the United States have contributed to this development. A bank taking a loss on a sale or swap of a loan to a developing country would not be required to reduce the book value of other loans to that country, provided the bank considers the remaining loans collectible. A few of the debtor countries whose liabilities are being traded at a discount have utilized the existence of the discount market to encourage a flow of private investments and to gain other advantages. The popular term for the conversion of discounted debt into local currency assets is a "debt-equity swap." "Debt conversion" would be a more appropriate term, since conversion of external debt instruments into domestic obligations can take place not only for foreign direct investment purposes, but also for more general purposes by residents or nonresidents of the debtor country. In essence, a foreign investor wishing to buy assets in a debtor country can, through a debt-equity swap, obtain local currency at a discount. The foreign investor, in effect, obtains a rebate on the purchase of the currency equivalent to the discount on the loan less the transactions costs of the debt-equity swap. Chile has a well-developed legal framework for the conversion of external debt into domestic assets. There is a similar procedure for the conversion of debt using foreign currency holdings by domestic investors. The figure shows the detailed steps involved in the debt conversion. Although they seem complicated, the central steps are conceptually simple. Debt-equity swaps are open only to nonresidents who intend to invest in fixed assets (equity) in Chile. The first step is to locate and buy at the going discount a Chilean debt instrument denominated in foreign currency. Next, with the intermediation of a Chilean bank, the foreign investor must obtain the consent of the local debtor to exchange the original debt instrument for one denominated in local currency and the permission of the central bank to withdraw the debt. Finally, the foreign investor can sell the new debt instrument in the local financial market and acquire the fixed assets or equity with the cash proceeds of the sale. The main difference between the debt-equity swap and the straight debt conversion is that the debt conversion is available to resident or nonresident investors with foreign currency holdings abroad. Also, once the conversion has taken place, the investor faces no restriction on the use of the local currency proceeds.

The debt conversion scheme allows the debtor country first to reduce the stock or the rate of growth of external debt. Second, it is a means to attract flight capital as well as foreign direct investment. Third, debt-equity swaps imply a switch from the outflow of interest and principal on debt obligations to the deferred and less certain outflows associated with private direct investment. For the commercial banks the swaps provide an exit instrument or a means to adjust the risk composition of their portfolio. For banks that wish to continue to be active internationally, losses on the outstanding portfolio can be realized at a time and on a scale of the bank's own choosing and by utilizing a market mechanism. The emergence of an active market in debt instruments of developing countries offers opportunities to both debtors and lenders. There are, however, obstacles to its development. Debtor countries must ensure that transactions take place at an undistorted exchange rate, otherwise the discounts on the debt may be outweighed by exchange rate considerations. In addition, long-term financial instruments in the domestic markets are needed to ensure that the conversion into domestic monetary assets does not increase monetary growth above established targets. The incentives for foreign investors will be nullified if the broader domestic policy environment is not conducive to inflows of foreign investment. Finally, a minimum regulatory framework is required. Documentation for debt restructuring must be adjusted to allow for prepayment for debt conversion purposes. Clear rules will facilitate the transactions. Overregulation, particularly in the form of administrative procedures for investment approval, would be a deterrence. |

| SOURCE: World Bank, World Development Report (New York: Oxford University Press, 1987), 22-23. Reprinted by permission. |

Designing an optimal international financial strategy is perhaps the most difficult task facing contemporary MNC managers. Thousands of business operations must be converted into their monetary equivalents and denominated in various currencies. Each currency is subject to fluctuations arising from governmental and social factors. In spite of the complexity of the task and the uncertainties involved, the international financial manager must assure the company's stakeholders that their interests in the company have been protected and that their investments have been put to optimal use.

To make good on this promise, the international financial manager must, first and foremost, strive to minimize the impact of changes in the macroeconomic environment on the company's daily cash flows, annual financial performance, and long-term economic or market value. Given that an MNC, with its affiliates around the globe, interacts with numerous macroeconomic environments, the MNC financial manager must be able to comprehend and anticipate the intentions and actions of many governments with diverse political and economic systems. A manager must be able to assess not only the intentions of the British government with respect to an appreciation of the pound, but also the magnitude and the likelihood of a potential appreciation of the yen against the dollar.

Until the beginning of the seventies, governmental policies generally had very little impact on a country's currency, primarily because a very robust international monetary system buffered business activities from sudden and unexpected changes in regime. The seventies, however, ushered in an epoch of unprecedented uncertainty. When, in 1971, President Nixon refused to honor the United States' obligation to exchange dollars for gold, he triggered a series of changes in the international monetary system that led to today's total confusion and turmoil.

Because of the complexity and uncertainty of the international capital markets that are the international financial manager's daily preoccupation, the first two functions of the international financial framework-exposure management and cash management-must be given precedence over the other two functions of capital budgeting and funding. Even the best capital budgeting and funding plans will be to no avail if inadequate attention is paid to the tremendous effects that external macro environmental changes can have on exchange rates, or to the potential impact of these changes on the company's cash flows, consolidated balance sheet, and economic value. It is the job of the international financial manager to anticipate or minimize these effects.

- 2436 reads