Enterprises should, within the framework of law, regulations and prevailing labour relations and employment practices, in each of the countries in which they operate,

(1) respect the right of their employees to be represented by trade unions and other bona fide organisations of employees, and engage in constructive negotiations, either individually or through employer's associations, with such employee organisations with a view to reaching agreements on employment conditions, which should include provisions for dealing with disputes arising over the interpretation of such agreements, and for ensuring mutually respected rights and responsibilities;

2(a) provide such facilities to representatives of the employees as may be necessary to assist in the development of effective collective agreements,

(b) provide to representatives of employees information which is needed for meaningful negotiations on conditions of employment;

(3) provide to representatives of employees where this accords with local law and practice, information which enables them to· obtain a true and fair view of the performance of the entity or, where appropriate, the enterprise as a whole;

(4) observe standards of employment and industrial relations not less favourable than those observed by comparable employers in the host country;

(5) in their operations, to the greatest extent practicable, utilise, train and prepare for upgrading members of the local labour force in co-operation with representatives of their employees 'and, where appropriate, the relevant governmental authorities;

(6) in considering changes in their operations which would have major effects upon the livelihood of their employees, in particular in the case of the closure of an entity involving collective lay-offs or dismissals, provide reasonable notice of such changes to representatives of their employees, and where appropriate to the relevant governmental authorities, and co-operate with the employee representatives and appropriate governmental authorities so as to mitigate to the maximum extent practicable adverse effects;

(7) implement their employment policies including hiring, discharge, pay, promotion and training without discrimination unless selectivity in respect of employee characteristics is in furtherance of established governmental policies which specifically promote greater equality of employment opportunity;

(8) in the context of bona fide negotiations* with representatives of employees on conditions of employment, or while employees are exercising a right to organise, not threaten to utilise a capacity to transfer the whole or part of an operating unit from the country concerned nor transfer employees from the enterprises' component entities in other countries in order to influence unfairly those negotiations or to hinder the exercise of a right to organise;

(9) enable authorised representatives of their employees to conduct negotiations on collective bargaining or labour management relations issues with representatives of management who are authorised to take decisions on the matters under negotiation.

*Bona fide negotiations may include labor disputes as part of the process of negotiation. Whether or not labour disputes are so included will be determined by the law and prevailing employment practices of particular countries.

SOURCE: OECD, Declaration on International Investment and Multinational Enterprises (Paris: Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, June 21, 1976).

The degree of transferability of management systems and techniques is a function not only of the host country's culture but also of the company's corporate culture, as the corporate culture is the vehicle through which management systems are transferred from the headquarters. Corporate culture has been variously defined as "a cohesion of values, myths, heroes, and symbols that has come to mean a great deal to the people who work [in a company]" and "the way we do things around here." 1 Whatever corporate culture is, it affects employees' attitudes. These attitudes influence behavior, which in turn affects people's performance and their contributions to organizational performance. Although some aspects of the corporate culture are shaped by the country culture (the macro culture ) and for this reason are the same for all organizations in a country, corporate culture is largely company-specific.

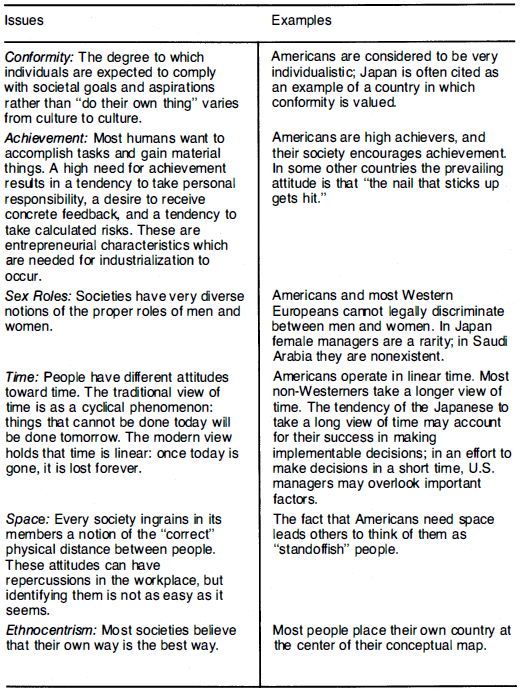

Though attitudes vary from person to person, an awareness of some generalizations about different countries' cultures can spare the international manager considerable pain. Figure 15.10 depicts six key concepts gleaned from theoretical and empirical cross-cultural research. These concepts relate to people's attitudes toward conformity, achievement, sex roles, time, space, and ethnocentrism. 2

Barrett and Bass 3 suggest the following guidelines for developing an understanding of the world of work in another culture:

(1) Study national socialization patterns. If the nation in question is highly fragmented, a number of socialization patterns may be operating at the same time; each must be addressed.

(2) Examine institutions peculiar to the country. For example, educational institutions may concentrate on preparation of a technical elite, or, alternatively, they may promote universal literacy.

(3) Consider individual traits that distinguish the nation from others. Included here would be distinct perceptual styles, intellectual reasoning, educational qualifications, and values.

(4) Focus on the predominant technology-for example, handicraft or unit, batch or mechanized, automated or process. This information should suggest viable organization objectives, predominant compensation policies, and other management considerations.

There have been any number of attempts to pinpoint specific cultural variables that explain cross-cultural variances. The empirical approach, developed by Hofstede, involves deriving salient dimensions empirically from attitudinal di1ferences. The main assumption underlying Hofstede's landmark longitudinal research 4 is that cultural di1ferences influence management and restrict the generalizability of certain organizational theories and management practices. In other words, culture-or what he calls "collective mental programming" is a circular and self-reinforced determinant of attitudes and behavior. This collective mental programming that people carry inside their heads tends to be incorporated into the institutions they build to assist them in their survival. These institutions, in turn, tend to promote and reinforce that culture.

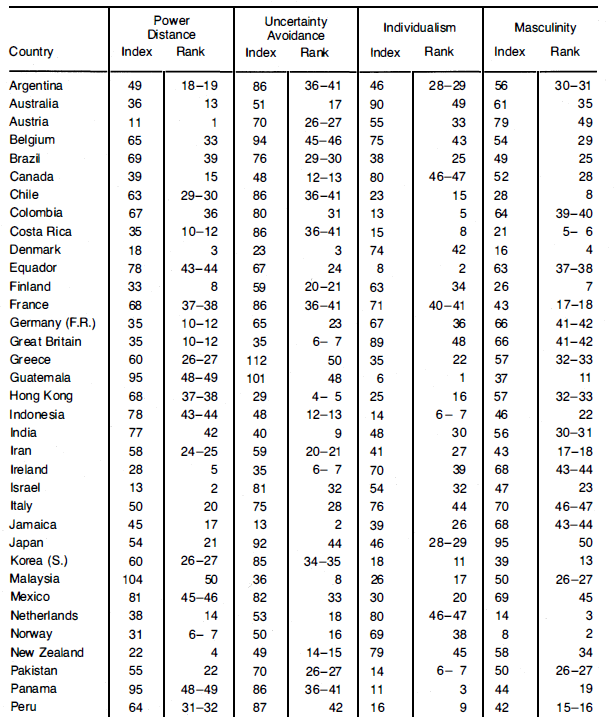

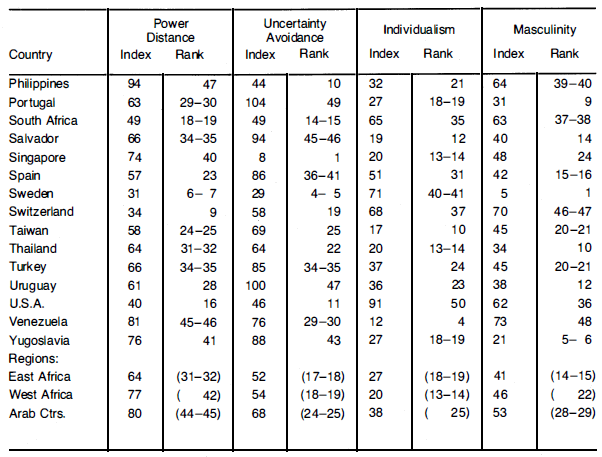

From his massive study covering fifty countries and some 116,000 employees of a major MNC, Hofstede distilled four basic dimensions of culture: power distance, uncertainty avoidance, individualism vs. collectivism, and masculinity vs. femininity. He then scored each country on the four dimensions; indices and ranks for all the countries are given in Figure 15.11.

Power distance is defined as the degree to which power in organizations is equally distributed. It is associated with the extent to which authority is centralized and leadership is autocratic. Malaysia, Guatemala, Panama, and the Philippines received the highest scores on this dimension (104, 95, 95, and 94, respectively).

SOURCE: G. Hofstede, "National Cultures in Four Dimensions," International Studies of Management and Organization 13, No. 2 (1983): 52. Reprinted with permission.

Uncertainty avoidance reflects the degree to which the society considers itself threatened by uncertain and ambiguous situations. The more threatened a society feels by uncertainty, the more formal rules it will set up and the less tolerance it will have for deviant behavior or new ideas. Greece, Guatemala, Uruguay, and Portugal are examples of countries with high indices of uncertainty avoidance.

Individualism vs. collectivism is an index of cultural perceptions of the relationship between the individual and the society as a whole. Hofstede ranked countries according to the degree to which they respect individualism. Not surprisingly, the wealthier countries tended to have more respect for individualism than did the poorer countries.

Masculinity vs. femininity is Hofstede's term for an index that expresses the degree to which a society values assertiveness and the acquisition of wealth ("masculinity") over compassion toward others ("femininity"). Hofstede argues that countries closer to the equator tend to be more "masculine," whereas those closer to the poles are more "feminine."

Hofstede's findings have implications for the design of systems for hiring, training, educating, compensating, appraising, disciplining, and even dismissing overseas employees. A manager can ill afford to ignore a host country's attitudes as revealed by the various indices. For example, whereas motivation, conflict resolution, industrial democracy, and careers for women and disadvantaged people are all important issues in the United States, serious discussion of them is likely to raise eyebrows in societies where formality and obedience are virtues, where women are thought to belong in the kitchen, and where a person's life work ends with his fifty-first birthday.

- 3539 reads