The tasks explained thus far, which are aimed at external exposure management and cash management, constitute one aspect of the international financial manager's job. The other aspect consists of capital budgeting (deploying financial resources) and funding (determining and evaluating funding options).

Capital budgeting is a process of balancing the advantages to be gained from possible uses of funds against the costs of alternative ways of obtaining the needed resources. Before capital budgeting can begin, the location of decision-making responsibility must be established. Financial decision making is one area in which corporate headquarters imposes strong controls via policies, procedures, and standards. Corporate headquarters generally specifies discretionary budgets, return requirements, and methods for evaluating and selecting projects. The actual evaluation of international investment proposals is a rather complicated process. A multitude of tax rates, exchange rates, inflation rates, and political risks must be carefully examined to establish an investment portfolio that maximizes stockholder wealth. Table 12.2 outlines some of the complexities of international capital budgeting.

Most MNCs follow a three-stage process in their appraisal of international projects.

Stage A: At the subsidiary level estimated cash flows from proposed disbursements and receipts are adjusted to account for exchange rate risks and political risks.

Stage B: At the headquarters level a plan is made regarding the amount, form, and timing of the transfer of funds; taxes and other expenses related to the transfer; and incremental revenues and costs that will occur elsewhere in the MNC.

Stage C: At the headquarters level the project is evaluated and compared with other investment projects on the basis of incremental net cash flows accruing to the system as a return on investment. 1

|

Capital budgeting for a foreign project uses the same theoretical framework as domestic capital budgeting: project cash flows are discounted at the firm's weighted average cost of capital, or the project's required rate of return, to determine net present value; or, alternatively, the internal rate of return that equates project cash flows to the cost of the project is sought. However, capital budgeting analysis for a foreign project is considerably more complex than the domestic case for a number of reasons: Parent cash flows must be distinguished from project cash flows. Each of these two types of flows contributes to a different view of value. Parent cash flows often depend upon the form of financing. Thus cash flows cannot be clearly separated from financing decisions, as is done in domestic capital budgeting. Remittance of funds to the parent must be explicitly recognized because of differing tax systems, legal and political constraints on the movement of funds, local business norms, and differences in how financial markets and institutions function. Cash flows from affiliates to parent can be generated by an array of nonfinancial payments, including payment of license fees and payments for imports from the parent. Differing rates of national inflation must be anticipated because of their importance in causing changes in competitive position, and thus in cash flows over a period of time. The possibility of unanticipated foreign exchange rate changes must be remembered because of possible direct effects on the value to the parent of local cash flows, as well as an indirect effect on the competitive position of the foreign affiliate. Use of segmented national capital markets may create an opportunity for financial gains or may lead to additional financial costs. Use of host government subsidized loans complicates both capital structure and the ability to determine an appropriate weighted average cost of capital for discounting purposes. Political risk must be evaluated because political events can drastically reduce the value or availability of expected cash flows. Terminal value is more difficult to estimate because potential purchasers from the host, parent, or third countries, or from the private or public sector, may have widely divergent perspectives on the value to them of acquiring the project. Since the same theoretical capital budgeting framework is used to choose among competing foreign and domestic projects, a common standard is critical. Thus all foreign complexities must be quantified as modifications to either expected cash flow or the rate of discount. Although in practice many firms make such modifications arbitrarily, readily available information, theoretical deduction, or just plain common sense can be used to make less arbitrary and more reasonable choices. |

| SOURCE: D . K. Eiteman and A. I . Stonehill, Multinational Business Finance, Fourth Edition ( Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley Publishing Co . , 1 983) , 330-33 1 . |

Capital budgeting is one area of international finance in which there has been a tremendous proliferation of analytical techniques, ranging from simple quantitative models to sophisticated large-scale computerized simulations. The model that has received the greatest attention in financial management literature is the Capital Assets Pricing Model (CAPM). This approach to capital budgeting allocates funds to projects on the basis of risk-adjusted returns, where returns are calculated from discounted cash flows. A complete treatment of the CAPM is beyond the scope of this book. What follows is a brief explanation.

Before any future cash flows are calculated for a project, management must make explicit its assumptions about the political risk and the exchange rate risk, as well as about the business climate in general. (Management's ways of dealing with these requirements will be explored in subsequent chapters when the investment decision is treated in more detail.) Much effort must go into formulating these assumptions.

Most managers adhere to some general principles when estimating, adjusting, and discounting cash flows. In estimating future exchange rates, managers usually use the Purchasing Power Parity Principle. 2 As explained in INTERNATIONAL FINANCE, purchasing power parity (PPP) refers to the equality of goods' prices across countries when measured in one currency. Movements in internal price levels correspond to movements in exchange rates:

where

= the spot rate (currency in Country 1/currency in Country

2) at time

= the spot rate (currency in Country 1/currency in Country

2) at time

the spot rate at time

the spot rate at time

=the price level in Country 1 at time

=the price level in Country 1 at time

the price level in Country 1 at time

the price level in Country 1 at time

= the price level in Country 2 at time

= the price level in Country 2 at time

=the price level in Country 2 at time

=the price level in Country 2 at time

In other words, the rate of change in the equilibrium exchange rate is proportional to the rate of change in the price levels in the two countries concerned.

Alternatively stated, if prices in Country 1 rise to 10% more than those in Country 2, Country 1 's exchange rate can be expected to depreciate by 10%, so that a particular amount of money will buy the same amount of goods in both countries. Boyd described this principle in 1801 by saying that exchange rates are in equilibrium when a buyer at a random point in time receives the same amount of goods for his or her money, regardless of which country he or she buys them from. The principle can be expressed as

where

=spot rate (currency in Country lIcurrency in Country 2)

=spot rate (currency in Country lIcurrency in Country 2)

=price level in Country 1

=price level in Country 1

=price level in Country 2

=price level in Country 2

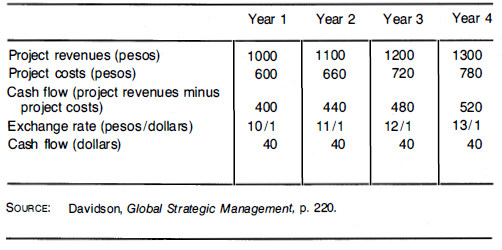

Figure 12.9 presents an example of projected cash flows under PPP.

In estimating the impact of interest rates on exchange rates, the relationship most commonly used is the so-called Fisher Open. This relationship, which was developed by Irving Fisher in 1896, is also known as Fisher's International Effect. It is based on the equality, across countries and currencies, of both expected returns on financial investment and borrowing costs. The Fisher Open expresses the equilibrium in international interest rates after adjustment for expected exchange rate movements:

where

spot rate at time

spot rate at time

= market expectations at time t regarding future spot

rate at time

= market expectations at time t regarding future spot

rate at time

= domestic interest rate for one period at

time

= domestic interest rate for one period at

time

= foreign interest rate for one period at time

= foreign interest rate for one period at time

According to the Fisher Open, the expected change in the exchange rate is reflected in the interest differential ( ) for assets under equal financial risk in two countries. This relationship is expressed in the principle of interest rate parity

(IRP), which says that the forward premium on one currency relative to another reflects the interest differential between the currencies. This relationship can be written as

) for assets under equal financial risk in two countries. This relationship is expressed in the principle of interest rate parity

(IRP), which says that the forward premium on one currency relative to another reflects the interest differential between the currencies. This relationship can be written as

where  , is the forward rate at time t for delivery of currency at

time

, is the forward rate at time t for delivery of currency at

time  .

.

Effective capital budgeting involves more than just financial criteria. The results of applying the Capital Assets Pricing Model must be supplemented with environmental analysis and strategic assessments. Figure 12.10 provides a summary of the three main subsystems of the capital budgeting system.

- 5304 reads