The decision to produce overseas is dictated by pressures from the external environment as well as from within the organization itself. Most governments around the globe would rather a foreign investor acquire a local factory or set up a new one than open a sales office or a distribution center. Factories create "visible" employment and revenues, which can be used by politicians as evidence of the success of their policies. At the micro level, the firm's evolution dictates that at some time it must seek gains somewhere outside its immediate and original market. As we have seen, products tend to follow a life cycle; an MNC can postpone the decline of a product by having it "migrate" to a new environment. Products that have reached the· mature stage at home can be "reborn" in a country where demand is sufficient to justify local production.

The existence of both external and internal pressures to move overseas is a necessary condition for overseas production. It is by no means sufficient, however. First, the firm's management must identify viable production opportunities abroad; second, management must possess the necessary attitude and know-how to take advantage of these opportunities. The firm must have a competitive advantage both in its product or technology and in its managerial know-how.

The first task in understanding the widely studied and discussed phenomenon of international production is to examine the role of the MNC in industrialization, a process that accomplishes the nation-state's goal of economic growth, and the role of the nation-state in international production, a means of accomplishing the MNC's goal of profit-making and capital accumulation (growth). Once the mutual interdependence of the MNC and the nation-state has been considered, the emphasis will shift to the production strategy per se. As noted, in international business, the production function encompasses much more than is conventionally implied by the term. In addition to the traditional process of manufacturing (that is, making usable things out of resources), production strategy incorporates the entire range of activities that must be performed in order to secure inputs for the manufacturing process and deliver the resulting outputs to appropriate markets.

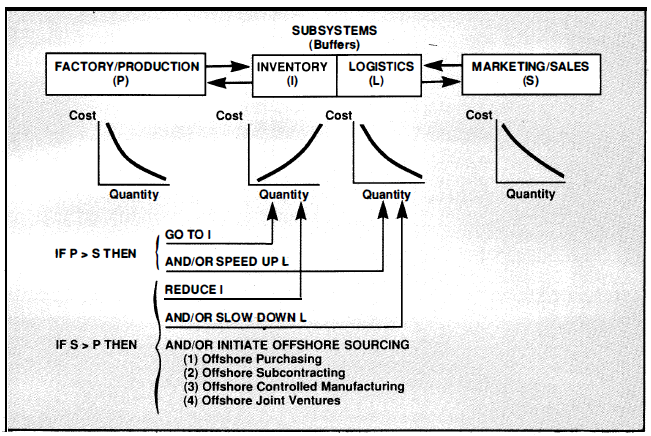

Figure 13.1 shows the main elements of a production strategy. The factory is the place where the transformation process takes place. The greater the number of items produced, the lower the production cost. The factory does not necessarily have to belong to the MNC. The MNC may subcontract to another company a portion of the production process or even the entire process. Or a subsidiary of an MNC may contract with another affiliate or with the MNC to do some of its production through a so-called sourcing contract.

The market is the place where buyers and sellers meet to exchange their goods and services. The marketing department of an MNC operates under the same principle as does the production department. Usually, but not always, the more efficient the marketing department is, the more it sells and the more quickly it sells it. Thus the marketing department would like always to have readily available quantities to sell.

The quantities of the product needed by the marketing department are procured through the inventory subsystem and delivered through the logistics subsystem. When quantities produced by the production department (the factory) cannot be sold quickly by the marketing department, they are temporarily put into the inventory subsystem. The functioning of the logistics subsystem can be slowed down or speeded up so as to accommodate the marketing department without frequent or unexpected jolts to the production line. The inventory and logistics subsystems thus act as buffers within the system.

Recognizing the importance of a continuous production line and large production runs, the Japanese have created a network of warehouses around the globe from which they feed their assembly plants and final markets. Since production interruptions can cause large set-up costs and delays, and since warehousing inventories in Japan is an expensive affair, given the skyrocketing cost of land and buildings, big Japanese trading companies regularly use ships, airplanes, port facilities, and free trade zones to guarantee an uninterrupted production process at home.

In sum, an international production strategy must provide answers to the following questions:

- From where should the firm supply the target market?

- To what extent should the firm itself undertake production (degree of integration)?

- What and where should it buy from others?

- Assuming that a firm opts to do at least some manufacturing, how should it acquire facilities?

- Should the firm produce in one plant or in many? Should the plants be related or autonomous?

- What sort of production equipment (technology) should the company use?

- What site is best?

- Where should research and development be located? 1

This chapter begins with a macro view of the subject of industrialization: its meaning, status, forms, shifts, and future prospects. Subsequently, the chapter switches to a micro view, examining the various tasks that a manager must perform in setting up an international production strategy. The overriding objective of an international production strategy is to guarantee worldwide organization and coordination of an MNC's affiliates' production plans so as to ensure a steady growth in profits.

- 1659 reads