The overall purpose of the light-dependent reactions is to convert light energy into chemical energy. This chemical energy will be used by the Calvin cycle to fuel the assembly of sugar molecules.

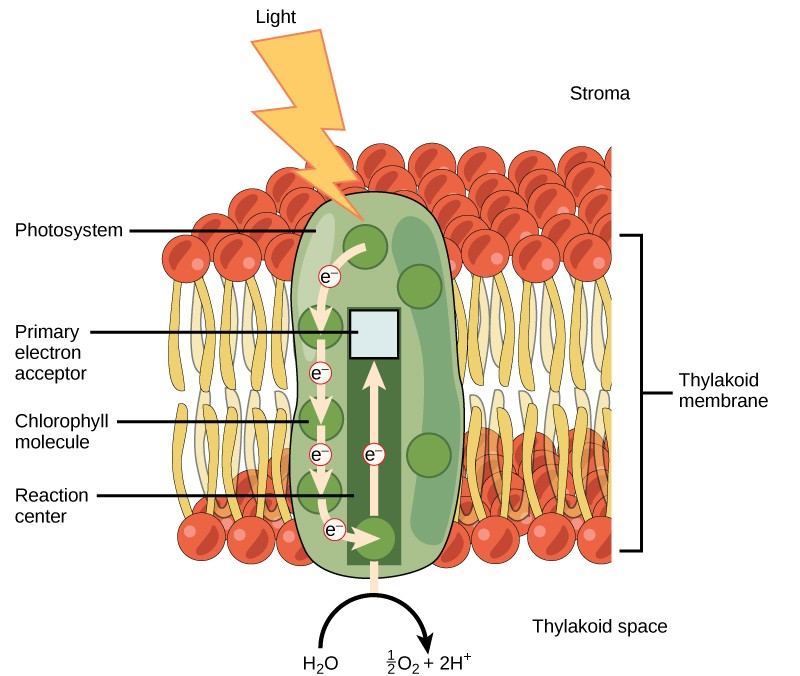

The light-dependent reactions begin in a grouping of pigment molecules and proteins called a photosystem. Photosystems exist in the membranes of thylakoids. A pigment molecule in the photosystem absorbs one photon, a quantity or “packet” of light energy, at a time.

A photon of light energy travels until it reaches a molecule of chlorophyll. The photon causes an electron in the chlorophyll to become “excited.” The energy given to the electron allows it to break free from an atom of the chlorophyll molecule. Chlorophyll is therefore said to “donate” an electron (Figure 5.12 ).

To replace the electron in the chlorophyll, a molecule of water is split. This splitting releases an electron and results in the formation of oxygen ( ) and hydrogen ions (

) and hydrogen ions ( ) in the thylakoid space. Technically, each breaking of a water molecule releases a pair of electrons, and therefore can

replace two donated electrons.

) in the thylakoid space. Technically, each breaking of a water molecule releases a pair of electrons, and therefore can

replace two donated electrons.

The replacing of the electron enables chlorophyll to respond to another photon. The oxygen molecules produced as byproducts find their way to the surrounding environment. The hydrogen ions play critical roles in the remainder of the light-dependent reactions.

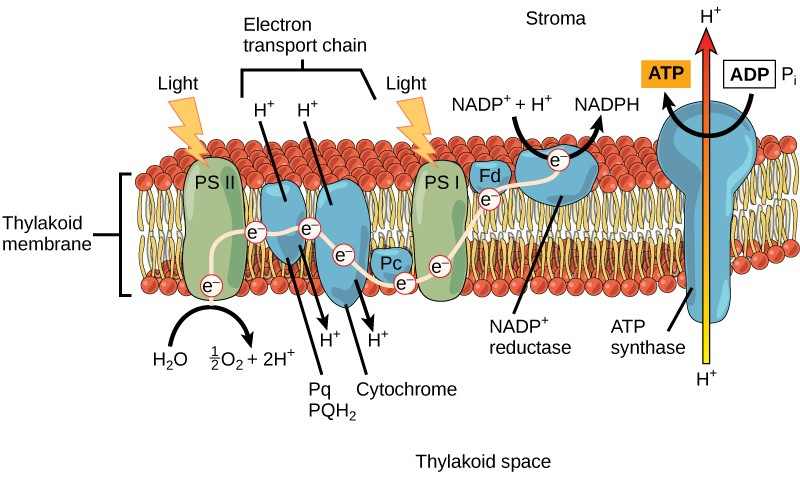

Keep in mind that the purpose of the light-dependent reactions is to convert solar energy into chemical carriers that will be used in the Calvin cycle. In eukaryotes and some prokaryotes, two photosystems exist. The first is called photosystem II, which was named for the order of its discovery rather than for the order of the function.

After the photon hits, photosystem II transfers the free electron to the first in a series of proteins inside the thylakoid membrane called the electron transport chain. As the electron passes along these proteins, energy from the electron fuels membrane pumps that actively move hydrogen ions against their concentration gradient from the stroma into the thylakoid space. This is quite analogous to the process that occurs in the mitochondrion in which an electron transport chain pumps hydrogen ions from the mitochondrial stroma across the inner membrane and into the intermembrane space, creating an electrochemical gradient. After the energy is used, the electron is accepted by a pigment molecule in the next photosystem, which is called photosystem I (Figure 5.13).

- 3987 reads