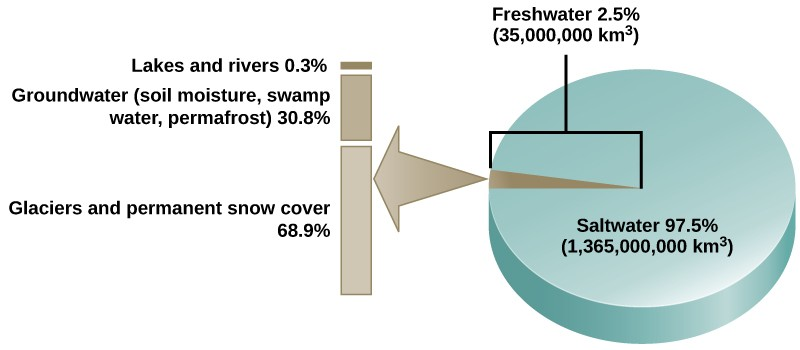

Water is essential for all living processes. The human body is more than one-half water and human cells are more than 70 percent water. Thus, most land animals need a supply of fresh water to survive. Of the stores of water on Earth, 97.5 percent is salt water (Figure 20.9). Of the remaining water, 99 percent is locked as underground water or ice. Thus, less than one percent of fresh water is present in lakes and rivers. Many living things are dependent on this small amount of surface fresh water supply, a lack of which can have important effects on ecosystem dynamics. Humans, of course, have developed technologies to increase water availability, such as digging wells to harvest groundwater, storing rainwater, and using desalination to obtain drinkable water from the ocean. Although this pursuit of drinkable water has been ongoing throughout human history, the supply of fresh water continues to be a major issue in modern times.

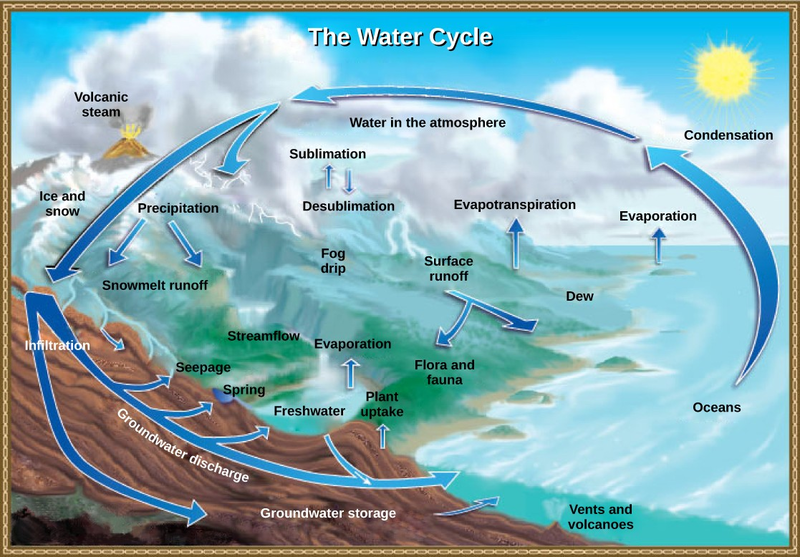

The various processes that occur during the cycling of water are illustrated in Figure 20.10. The processes include the following:

• evaporation and sublimation

• condensation and precipitation

• subsurface water flow

• surface runoff and snowmelt

• streamflow

The water cycle is driven by the Sun’s energy as it warms the oceans and other surface waters. This leads to evaporation (water to water vapor) of liquid surface water and sublimation (ice to water vapor) of frozen water, thus moving large amounts of water into the atmosphere as water vapor. Over time, this water vapor condenses into clouds as liquid or frozen droplets and eventually leads to precipitation (rain or snow), which returns water to Earth’s surface. Rain reaching Earth’s surface may evaporate again, flow over the surface, or percolate into the ground. Most easily observed is surface runoff: the flow of fresh water either from rain or melting ice. Runoff can make its way through streams and lakes to the oceans or flow directly to the oceans themselves.

In most natural terrestrial environments rain encounters vegetation before it reaches the soil surface. A significant percentage of water evaporates immediately from the surfaces of plants. What is left reaches the soil and begins to move down. Surface runoff will occur only if the soil becomes saturated with water in a heavy rainfall. Most water in the soil will be taken up by plant roots. The plant will use some of this water for its own metabolism, and some of that will find its way into animals that eat the plants, but much of it will be lost back to the atmosphere through a process known as evapotranspiration. Water enters the vascular system of the plant through the roots and evaporates, or transpires, through the stomata of the leaves. Water in the soil that is not taken up by a plant and that does not evaporate is able to percolate into the subsoil and bedrock. Here it forms groundwater.

Groundwater is a significant reservoir of fresh water. It exists in the pores between particles in sand and gravel, or in the fissures in rocks. Shallow groundwater flows slowly through these pores and fissures and eventually finds its way to a stream or lake where it becomes a part of the surface water again. Streams do not flow because they are replenished from rainwater directly; they flow because there is a constant inflow from groundwater below. Some groundwater is found very deep in the bedrock and can persist there for millennia. Most groundwater reservoirs, or aquifers, are the source of drinking or irrigation water drawn up through wells. In many cases these aquifers are being depleted faster than they are being replenished by water percolating down from above.

Rain and surface runoff are major ways in which minerals, including carbon, nitrogen, phosphorus, and sulfur, are cycled from land to water. The environmental effects of runoff will be discussed later as these cycles are described.

- 3378 reads