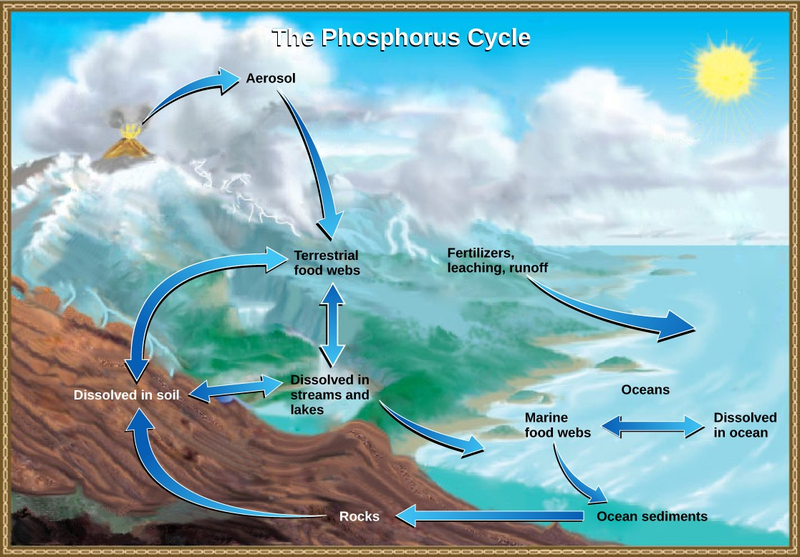

Phosphorus is an essential nutrient for living processes; it is a major component of nucleic acids and phospholipids, and, as calcium phosphate, makes up the supportive components of our bones.

Phosphorus is often the limiting nutrient (necessary for growth) in aquatic, particularly freshwater, ecosystems. Phosphorus occurs in nature as the phosphate ion ( ). In addition to phosphate runoff as a result of human activity, natural surface runoff

occurs when it is leached from phosphate-containing rock by weathering, thus sending phosphates into rivers, lakes, and the ocean. This rock has its origins in the ocean. Phosphate-containing

ocean sediments form primarily from the bodies of ocean organisms and from their excretions. However, volcanic ash, aerosols, and mineral dust may also be significant phosphate sources. This

sediment then is moved to land over geologic time by the uplifting of Earth’s surface. (Figure

20.13)

). In addition to phosphate runoff as a result of human activity, natural surface runoff

occurs when it is leached from phosphate-containing rock by weathering, thus sending phosphates into rivers, lakes, and the ocean. This rock has its origins in the ocean. Phosphate-containing

ocean sediments form primarily from the bodies of ocean organisms and from their excretions. However, volcanic ash, aerosols, and mineral dust may also be significant phosphate sources. This

sediment then is moved to land over geologic time by the uplifting of Earth’s surface. (Figure

20.13)

Phosphorus is also reciprocally exchanged between phosphate dissolved in the ocean and marine organisms. The movement of phosphate from the ocean to the land and through the soil is extremely slow, with the average phosphate ion having an oceanic residence time between 20,000 and 100,000 years.

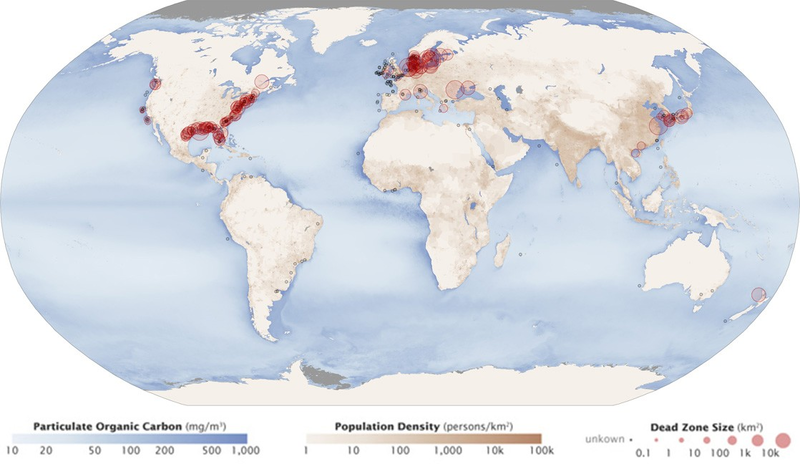

Excess phosphorus and nitrogen that enter these ecosystems from fertilizer runoff and from sewage cause excessive growth of algae. The subsequent death and decay of these organisms depletes dissolved oxygen, which leads to the death of aquatic organisms, such as shellfish and finfish. This process is responsible for dead zones in lakes and at the mouths of many major rivers and for massive fish kills, which often occur during the summer months (see Figure 20.14).

A dead zone is an area in lakes and oceans near the mouths of rivers where large areas are periodically depleted of their normal flora and fauna; these zones can be caused by eutrophication, oil spills, dumping toxic chemicals, and other human activities. The number of dead zones has increased for several years, and more than 400 of these zones were present as of 2008. One of the worst dead zones is off the coast of the United States in the Gulf of Mexico: fertilizer runoff from the Mississippi River basin created a dead zone of over 8,463 square miles. Phosphate and nitrate runoff from fertilizers also negatively affect several lake and bay ecosystems including the Chesapeake Bay in the eastern United States.

Careers IN ACTION

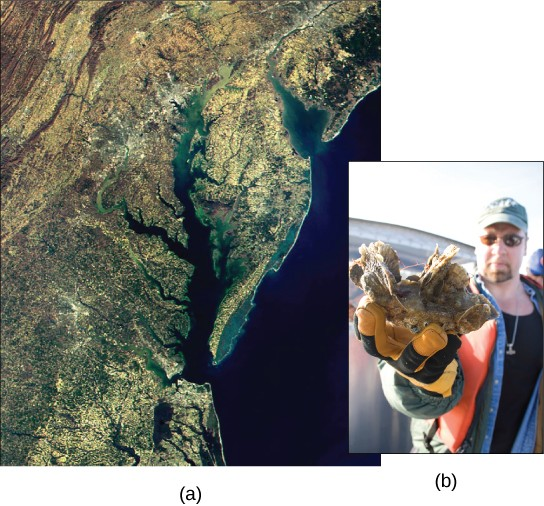

Chesapeake Bay

Of particular interest to conservationists is the oyster population (Figure 20.15); it is estimated that more than 200,000 acres of oyster reefs existed in the bay in the 1700s, but that number has now declined to only 36,000 acres. Oyster harvesting was once a major industry for Chesapeake Bay, but it declined 88 percent between 1982 and 2007. This decline was caused not only by fertilizer runoff and dead zones, but also because of overharvesting. Oysters require a certain minimum population density because they must be in close proximity to reproduce. Human activity has altered the oyster population and locations, thus greatly disrupting the ecosystem.

The restoration of the oyster population in the Chesapeake Bay has been ongoing for several years with mixed success. Not only do many people find oysters good to eat, but the oysters also clean up the bay. They are filter feeders, and as they eat, they clean the water around them. Filter feeders eat by pumping a continuous stream of water over finely divided appendages (gills in the case of oysters) and capturing prokaryotes, plankton, and fine organic particles in their mucus. In the 1700s, it was estimated that it took only a few days for the oyster population to filter the entire volume of the bay. Today, with the changed water conditions, it is estimated that the present population would take nearly a year to do the same job.

Restoration efforts have been ongoing for several years by non-profit organizations such as the Chesapeake Bay Foundation. The restoration goal is to find a way to increase population density so the oysters can reproduce more efficiently. Many disease-resistant varieties (developed at the Virginia Institute of Marine Science for the College of William and Mary) are now available and have been used in the construction of experimental oyster reefs. Efforts by Virginia and Delaware to clean and restore the bay have been hampered because much of the pollution entering the bay comes from other states, which emphasizes the need for interstate cooperation to gain successful restoration.

The new, hearty oyster strains have also spawned a new and economically viable industry—oyster aquaculture—which not only supplies oysters for food and profit, but also has the added benefit of cleaning the bay.

- 4023 reads